Excerpted from The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2022 by Isaac Butler. A review of the book can be found here.

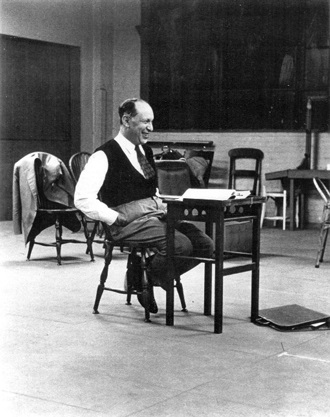

After the Moscow Art Theatre left New York, a newly inspired Lee Strasberg enrolled at the Clare Tree Major School of the Theatre. The curriculum followed the rulebook Lee would eventually set on fire: The teachers demonstrated the proper way to deliver a line, and the students imitated them. According to Phoebe Brand, a classmate of Strasberg’s, he was “a most unactory sort…he was distinctly withdrawn. You did not get friendly with him or link your arm through his or anything. He was a strange one.” Like everyone else who knew Strasberg then, she did not understand why—or how—such a silent and undemonstrative person could have any hope of being an actor.

Strasberg must have been open about his discontent with the Clare Tree Major method, because one day a fellow student told him that he had heard of a different school, called the American Laboratory Theatre, that sounded like what Strasberg was looking for. It taught the methods of Stanislavski, and it was run by two Russians. Their names, the student said, were Richard Boleslavsky and Maria Ouspenskaya.

Ouspenskaya joined the Lab’s faculty as an acting teacher in November 1923, when the Moscow Art Theatre returned to New York for a yearlong extension of its American tour. When the MAT traveled home to Russia, she stayed behind and became the Lab’s primary acting teacher. She remained in the United States for the rest of her life. It was, she would later say, “the reverse gypsy in me…I got myself settled in America and I’ve never had the slightest inclination to get away from it.”

Ouspenskaya provided her students with concrete step-by-step instruction in Stanislavski’s “system.” She had been one of the first to learn it when she studied at the Adashev School in 1909, and she had worked frequently with Boleslavsky, to whom she was devoted. A diminutive woman who looked far older than her 38 years, Ouspenskaya cultivated a severe persona, smoking thin black cigars and wearing a monocle. In class, she was famous for her terrifying manner. You did not smoke or eat in her classes. You came dressed to move and work, and you approached acting with a pious seriousness. Her criticism was unremittingly harsh; compliments were not forthcoming. As Donald Keyes, one of her students, described it, “to be in one of Madame’s classes could be an agonizing emotional experience.” She frequently reduced students to tears with her critiques.

She also drank bathtub gin during class. In the early years of the Lab, she drank it out of a medicine bottle, claiming it was for a cough. A student assistant would administer the bootleg booze out of a tablespoon. When class went poorly, her cough magically became worse. On at least one occasion, she went through the whole bottle. In later years, she tried to disguise her gin as regular water, poured out of a pitcher into a glass. Neither ruse fooled anyone.

But even when she was drunk, her verbal brutality served a pedagogical purpose. She wanted to push actors past their fears and break down their limitations. If they could survive her, they could survive any audition, any spell of stage fright, any absurd or difficult request a director made of them. Outside class, her students found her warm and generous. You could visit her at any hour of the night and she would wake up and help you with your acting, free of charge.

Her teaching was a performance, perhaps the greatest of her life. When she entered the class, she would say to her students, “Make for me friendly atmosphere!” and only once this had been done would she begin. Little documentation of these classes survives. Some of the most detailed notes are those taken by Lee Strasberg during his first few days of studying with her. “The first thing Mme Ouspensk[aya] asked us was to get up and walk,” he wrote. A student simply walking around the room with no other guidance would become self-conscious, and as they realized they were being observed, this simple act of moving naturally would become impossible. Next, she asked them to walk while thinking about something. Immediately, the class saw the improvement: Having a purpose made natural behavior easier to create, even while you were being watched. “Always have a reason/problem,” Strasberg noted her saying. An actor needed “a cause for appearing on the stage.”

From Ouspenskaya, Strasberg learned that “the main points in the system are Concentration and Affective Memory.” The latter was essential because “one deals with dead and imaginary things on the stage [and] these things will appear alive if you have been trained in Affective Memory.” Props were not enough. You had to imbue them with real meaning, behaving as your character within imagined circumstances. Only affective memory would let you do that.

To hone their memory, actors in Ouspenskaya’s class performed sense memory exercises and worked with invisible objects. They would recall how touching velvet felt, as opposed to touching silk. They would hold their hands under nonexistent water, first hot, then cold. They passed an imaginary wounded bird from student to student. They drank out of make-believe water glasses and ate nonexistent grapefruits. The point was not to mime but to use memory and imagination to capture the feeling of drinking the water and eating the fruit.

Soon Ouspenskaya introduced the class to “one-minute plays.” She would propose a scenario—in the Lab’s argot, “give them a problem”—and they would act it out. Madame would often add additional problems to the exercise as it went along, changing characterization and circumstances until the one-minute play grew in complexity. In one they “had to be Indians, with the problem to present something to white-man”; in another, Strasberg had to be a schoolteacher who confiscated a present from one of his students, played by an actress named Estelle. She immediately started crying. Ouspenskaya reprimanded her. “You didn’t feel like crying,” she said, “but you did so.” The lesson: “Always establish the mood within you, and don’t show more than you have, or it looks false. Always show less, and the imagination of the audience will magnify it.” Thirty-five years later, Strasberg would tell his student Al Pacino the same thing.

Boleslavsky taught through periodic lectures and his direction of the American Lab Theatre’s plays. His persona was the opposite of his partner’s. While “Madame” was severe and uncompromising, Richard was warm, avuncular, and modest; students were welcome to use his nickname, Boley. Ever secretive, he almost never spoke of Stanislavski or his past successes in the theatre.

Boleslavsky was not a theorist. His true gift lay in his pragmatism; even his most philosophical flights were paired with concrete instructions. He would expound on emotion—calling it “the most important and most difficult and precise part of the work of an actor”—and explicitly reject using imagination to find emotion because “in art you cannot deal with unreal things.” But he also would give his students a step-by-step method for building a catalog of affective memories to use onstage that’s far more helpful than most writing on the subject. First, Boley explained, you simply notice when a feeling arises seemingly from nowhere. Perhaps you feel a loneliness that creeps up on you, unbidden. Next, you “catch” this feeling, like a moth in your hands, and try to figure out what sensory cue triggered it. Perhaps it was a cloudy day, and someone was barbecuing next door, and those two things together reminded you of when you first moved to a new city and didn’t know anyone. You then write this feeling and its trigger down in a notebook. A few weeks later, you should attempt to make yourself feel that loneliness again by recollecting not the actual emotion, but the gray light of a cloudy day and the smell of chicken hitting a hot grill. If you can accomplish this, you can then attempt to complete some kind of two-to-three-minute task, like going to get the mail while holding on to the feeling the entire time. If you keep doing this for various emotions, you will build a repertoire of feelings in your “golden book.” Then, as you study a role and see a moment that requires a particular emotional state, you can return to your golden book and summon it.

“This is very interesting,” Strasberg wrote in his notebook. This “way of working on a part is very near the psychoanalytic method.” Perhaps Strasberg was underselling his own enthusiasm, or perhaps he had not yet realized what he had stumbled onto. But these ideas would become central to his thinking about acting for the rest of his life. “What I had gotten was extraordinary,” Strasberg later said of the Lab. “It changed my entire perspective. I had read Freud and already knew the things that go on in a human being without consciousness, but they showed me what it meant. They gave me the key to things I’d seen, heard, and known but had no means of understanding.”

At the same time, he began to see his teachers’ limits. The actual work done on the stage at the American Lab Theatre did not particularly interest him. He felt that Boleslavsky was “not a creative artist” and that the Lab had failed to become distinctly American. After only a few months of study, believing he had gotten all he needed from the Lab, Strasberg struck out on his own to become a professional actor.

Soon after Lee Strasberg left, another seeker found her way to the Lab. Stella Adler had been, in her own words, “born into a Kingdom.” Her father, Jacob, and mother, Sara, were two of the most famous and beloved people in the Yiddish-speaking world. The Adler children—or perhaps, given Jacob’s world-spanning lechery, the recognized Adler children—began acting as soon as they could remember their lines and were treated like royalty.

But by 1925, the Yiddish Theatre had stopped making sense to her, and yiddishkeit society felt increasingly confining. Over a decade had passed since the peak of Jewish immigration to New York. Stella’s generation was assimilating, and Yiddish theatre’s cultural prominence was collapsing as a result. It would never be a vehicle for a lifelong career as an actress, but she didn’t know what else to do.

She went to the library in search of a solution, looking up “techniques of acting” in the card catalog of the midtown branch and pulling books off the shelves. One of the books may well have been My Life in Art, Konstantin Stanislavski’s recently published memoir—a memoir that contains almost nothing in its 583 pages about the technique of acting. A young man saw her in the stacks and asked her if she had seen the production of Troubetskoy’s The Sea Woman’s Cloak that was being put on in some kind of apartment in the Village. He believed it was connected to a school.

That day, Stella entered the American Lab Theatre’s performance space, which seated about 20 people. “I was astonished at a number of things,” she recalled later. “One, the absolute, fantastic production. The acting, and the audience. In the audience was a woman with a monocle, in black, and she was like a[n] etching . . .” That striking black-clad Cyclops was, of course, Maria Ouspenskaya. “I went to the Laboratory Theatre and I said I wanted to join them, and they took me in immediately.” Stella began studying there and joined the company, but from the start her relationship with the Lab was a stormy one. Boley offered her a role in The Scarlet Letter shortly after she joined, and she turned it down because it had no lines. She felt he never fully trusted her again.

While Stella was finding her footing at the Lab, Lee was beginning his career as a professional actor. Philip Loeb, the Theatre Guild’s casting director, gave him a few walk-on roles in the Guild’s shows. In one of the first—as a Ku Klux Klan member in John Howard Lawson’s Processional—Lee met a young actor and pianist named Sanford Meisner. The two became friends. Then, while waiting in a line to audition for a play, they met Harold Clurman, a former apprentice with the Provincetown Players who was now working as a script reader and bit player for the Guild. He had seen Lee act—he remembered him as “very short, intense-looking, with skin drawn tightly over a wide brow”—and their shared background as Jewish intellectuals from the Lower East Side helped a series of chance encounters blossom into an intense friendship.

Intrigued by Strasberg’s theories about acting and directing, Clurman ventured to the Chrystie Street Settlement to watch his friend experiment with affective memory and other techniques. By then, Clurman had begun to grow disillusioned with the Guild. Too often he saw good plays put on by good directors with good casts die onstage because no one had a clear point of view into the material, or any real understanding of how it spoke to people’s lives. Clurman’s cousin Aaron Copland had begun to figure out how to create a new American sound in symphonic music, one that used the tools and techniques developed in Europe and adapted them to America’s yearnings, its mysteries and struggles, its potential and its pain. Someone needed to do this for theatre. Perhaps Clurman—or he and Strasberg—could be the ones to do it.

By 1929, Boley had left the Lab to direct in Hollywood, and the stock market crash would be the last straw for the school. But the dreams of the Lab were far from dead. In a 1926 article in The New York Times, Boleslavsky had articulated a possible path forward. “The prophets of repertory in America,” he wrote, would have to “go into the life of the nation and understand what kind of repertory theatre the nation wants. If they find an answer, they will conquer.” By the end of the 1920s, Lee Strasberg and Harold Clurman were beginning to find their answer. In talks backstage at the Guild and in its offices, in diners and in each other’s apartments, they envisioned a truly American repertory company that took the best ideas of Europe and adapted them for American plays, American actors, and American social problems. A company could accomplish this only if they trained together and shared a technique of acting. That technique would be based on the “system,” but by then, they found that word too grand. They wanted a name for their technique that was in a lower key, more descriptive, and simpler. They called it their method.