Growing up, I insisted we call him “Songheim.” I thought that was his name, a moniker fit for his vocation. And I thought he was mine. Part of my family. Musical, like us. Language-obsessed, like us. Neurotic, like us. Jewish, like us.

I don’t remember learning about Stephen Sondheim’s Judaism, just as I don’t remember first hearing his songs. He was just always there—and he’s never left me since, even at times when I very nearly left Judaism. From age 18 to 28, in fact, I refused to enter a synagogue. When I finally returned this past year for the High Holidays, I couldn’t remember the words or the tunes. My emotional link to the ritual felt like a bad radio signal, staticky, unpredictable, fading in and out. Afterward I had to admit that the music of my people didn’t live on in me. Not like Sondheim’s does, anyway. Still, following his death, reading tweets and tributes that ended with, “May his memory be a blessing,” I felt a twinge of kinship. A feeling of connection. A sense that Sondheim’s Judaism, however ambivalently held, mattered.

But as often proves the case with this artist—famously elusive on so many topics—an unambiguous connection between Sondheim and Judaism struggles to find its footing. Jewishness haunts his canon, yet rarely manifests directly. Quick-talking, bespectacled Charles Kringas of Merrily We Roll Along, first played by Lonny Price, has to be Jewish…right? How about the worrywart Baker of Into the Woods, indelibly linked through the PBS broadcast with Chip Zien? Bobby in Company displays the neurosis of a Jew but not the heritage. Judaism shows up in that quintessentially New York play twice, though, once when cold-footed bride Amy exclaims that she’s marrying her “very own Jew” and once when the Jew in question, Paul, calls Bobby “bubi.”

As an explicitly Jewish character, Paul occupies a lonely spot in the Sondheim corpus. Contrast this paucity, however, with his wealth of Jewish collaborators: Zien and Price, but also Mandy Patinkin, Leonard Bernstein, Hal Prince, James Lapine, and John Weidman. In fact, closely examine some of Sondheim’s favorite anecdotes, and you’ll find that many of them feature an all-Jewish cast. He loved, for instance, to tell and retell how he ended the first draft of Gypsy’s show-stopping “Rose’s Turn” with a series of discordant harmonics illustrative of the nervous breakdown the character has just experienced. Out-of-town tryout audiences hated it, and it nearly ruined the show. Only the combined arguments of Arthur Laurents, Jule Styne, and Sondheim’s mentor Oscar Hammerstein II eventually prevailed on him to change the music, yielding to the triumphant, blaring chords that now end the song.

That is not a Jewish story—except, of course, that it is. From its squabbling chorus of fractious Jewish men (“creative overlapping,” it’s euphemistically called today); to Mama Rose in her tragic, overbearing glory (herself haunted by the specter of Sondheim’s legendarily difficult Jewish mother); to the obsessive relitigation of an argument over and over, long after it has reached its conclusion. All summon for me what Judaic Studies scholar Daniel Boyarin playfully terms “Jewissance” (riffing off of Lacan’s jouissance): the pleasure of feeling connected to a heritage that goes back millennia, to people you have never met. A Jewy-ness that cultural theorists in the 1990s would call an “affect” and that I, a millennial born in the 1990s, refer to as a “vibe.”

It’s that initial impulse not to finish “Rose’s Turn” that helps elucidate a still deeper connection between Sondheim and Judaism. In this line of thought I’m indebted to writer Dara Horn, who articulated in her most recent book, People Love Dead Jews, the Jewish sense of ending. In Horn’s conception, Jewish narratives do not culminate in satisfying finales. This pattern goes all the way back: Unlike the Christian ur-narrative of resurrection and redemption, the Torah ends without resolution. Instead, Moses dies while the Israelites continue to strive for the Promised Land—and when they finish reading this story, millennia of Jews have turned back to its start and begun to read again. The Talmud reifies this tradition of rereading, codifying centuries’ worth of rabbinic arguments over the edicts, phrases, and individual words that make up Jewish law. Together, the Torah and the Talmud teach that narratives never really end. That debate can rage eternally. And that the past lives with us, every day. Horn argues that many works by Jewish artists adhere to these traditions, rendering them difficult to analyze through conventional critical tools, easily misunderstood as unsatisfying and unfinished.

This question of keeping a story alive, of passing it down to those who come after, is a central preoccupation of Judaism. The Passover Seder embodies this goal most actively, calling on participants to worship “as though you yourself came out of Egypt.” Such an impulse shines through the ending of Into the Woods, which depicts a newly widowed Baker holding his child while the ghost of his wife urges, “Tell him the story of how it all happened. Be father and mother, you’ll know what to do.” Though the musical ends with the dulcet “Children Will Listen,” it emphasizes that parents will not always know what to say; and that the tales they tell may have tragic endings. As with many Sondheim works, Into the Woods achieves this power by troubling its own structure. Like Sunday, the work encompasses a pristine, satisfying first act, and a famously messy second. While Act One of Sondheim’s so-called sellout musical ties up its interlocking narrative with a neat bow, its Act Two unravels them, transforming the fairy tale adaptation into an exploration of generational trauma, cataclysm, and the sustaining power of narrative. Although “father, like son” will continue to make “one another’s terrible mistakes,” a community rallying to tell the same story will be enough, must be enough, to ensure its own survival. Jewissance, after all.

So, like the famous and beloved flop Merrily We Roll Along, my attempt to understand Stephen Sondheim’s Judaism begins in his endings. Many have divided critics and audiences since their first stagings, but perhaps none more so than Act Two of Sunday in the Park with George. The debate rages to this day: In his recent remembrance of the composer, Adam Gopnik called Sunday’s first act “the single best thing in musical theatre” and the second act “almost unsalvageable.” I can’t agree. Sunday’s Act One concludes as Georges Seurat unveils his pointillist masterpiece. Act Two ends on a blank stage while the painter’s great-grandson, George, intones, “White. A blank page or canvas.” A direct quote from the opening lines of the play. Almost. For while Seurat speaks the musical’s first words—”White. A blank page or canvas”—George now reads them from a grammar book marked up by his great-grandmother Dot, Seurat’s mistress. The next line from James Lapine’s script, the final line of Sunday, makes clear the significance of this shift. In Act One, Seurat continues, “The challenge: bring order to the whole.” But the modern George reads, “His favorite. So many possibilities…” George has not inherited a clear or uncomplicated legacy. Instead, he now engages in direct conversation with a remembered past captured in language. A past that has already changed based on who has passed it on and how they have interpreted it. The intergenerational conversation, what Tony Kushner in Angels in America called the characteristically Jewish “chamber of circumspection,” is the point.

Sweeney Todd explores the line between vengeance and justice. Company questions the boundaries of community and concludes with the notion that “Being Alive” is enough (“More life,” as Kushner blesses us in Angels). Even the weirder musicals fit this pattern: Anyone Can Whistle depicts the isolation of the prophet, the tetchy anguish of the lone truth teller. Road Show ends in limbo, its now-dead conman characters seeing in “the road to eternity” a “road to opportunity”—a chance, at last “to get it right.” It’s one of the most thoroughly Jewish conceptions of the afterlife I’ve ever found.

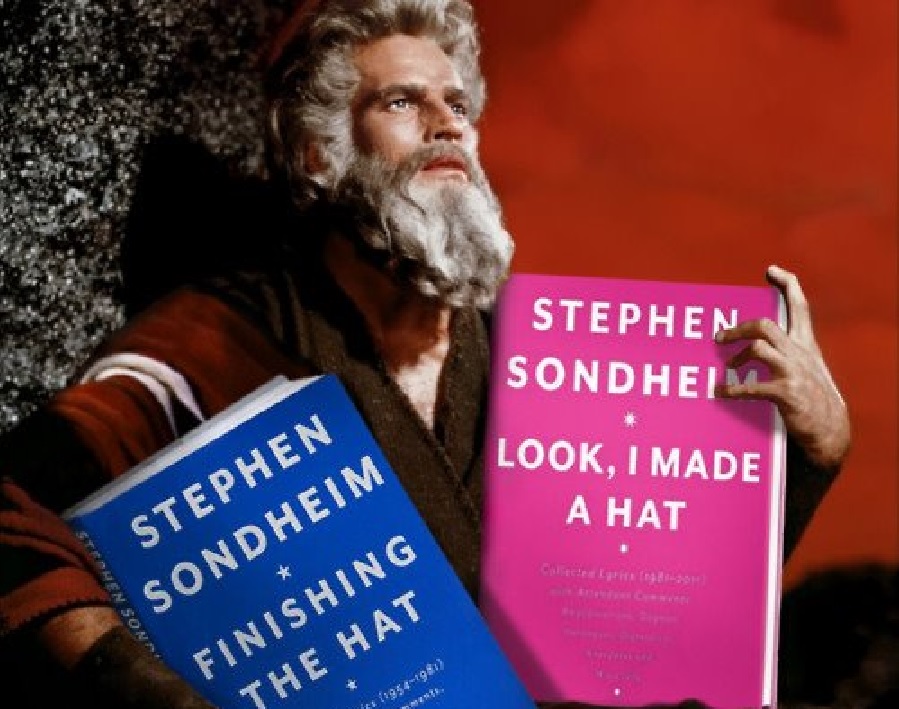

Sondheim’s famous relationship to allusion, the way he could be endlessly referential without sliding into deferential, summons up the Talmudic traditions of study and debate. In her review of Look, I Made a Hat (the second volume of Sondheim’s unconventional memoir; the first was called Finishing the Hat), Entertainment Weekly critic Lisa Schwarzbaum called the work “Talmudically thorough.” She was referring to the famously granular nature of the older text, and the comparison is apt. Finishing the Hat presents itself as “Collected Lyrics with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines, and Anecdotes.” Look, I Made a Hat revises this subtitle, promising “Collected Lyrics with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes, and Miscellany.” In the pages of both volumes, Sondheim cites, analyzes, and argues with his own influences, from Gilbert & Sullivan to Cole Porter to Noël Coward to Bernstein to Hammerstein; he ventures into the future, too, with references to Jonathan Larson, Craig Carnelia, and Lin-Manuel Miranda. One forms the image of a convocation of composers bickering in Sondheim’s mind, not unlike the associations called up by the Talmud. In fact, the memoir’s very form, a lyric book surrounded by annotations (many of which have their own extensive footnotes), mirrors the Talmud, flanking a central text with its many contradictory interpretations.

Here I must acknowledge that I’ve never read a word of the Talmud. I have no desire to swamp myself within that particular intratextual quagmire, and my only knowledge of its study comes from the Chaim Potok YA classic The Chosen. I have, however, studied the two volumes of Stephen Sondheim’s memoir. It’s an exhaustive, even exhausting text. When he analyzes the climactic “Move On” from Sunday, the composer-lyricist jumps from his own lyrics to French poetry to a discussion of creative abandonment to an explication of musical form. The meat of the annotation—with Sondheim’s handwritten score to its left and a picture of Bernadette Peters and Mandy Patinkin underneath—agonizes over the adverb in the stanza: “Stop worrying if your vision/ Is new/ Let others make that decision/ They usually do.” Painstakingly, Sondheim weighs the pros and cons of the linguistically correct choice (“eventually”) with the demands of his meter (which requires one fewer syllable). Though “usually” ultimately triumphs, he considers it “imprecise, both sonically and tonally.” Fans of the song (which is to say, most readers) reckon with a choice: Revise one’s own opinion of the gorgeous lyric or disagree with one’s hero. Either way, the clarity of “Move On” grows more complex, the future pleasure of listening enriched by the present experience of reading. The intergenerational debate continues.

Influential theatre studies scholar David Savran warns of musical theatre’s “seduction.” He considers the genre “single-mindedly devoted to producing pleasure” and critiques the mindless devotion it can engender. Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat offer a rebuttal to this view. You cannot read these books without engaging Sondheim’s intellect, delving into his own creative struggles, or reexamining his work. Exactingly focused and yet intentionally discursive, this text enforces a type of scholarship. It encourages thinking and rethinking, debate, critique. It defies linear reading and in fact demands re-reading. Jewissance again.

Rabbi, in Hebrew, means teacher or scholar. I think Sondheim might hate it if I called him a rabbi. But, in the wake of his death, hundreds came forward to describe how Stephen Sondheim taught them. Not just the great musical theatre writers and playwrights (Lin-Manuel Miranda, Lynn Nottage) whose careers he furthered, but those to whom he sent typewritten notes of gratitude and praise (now memorialized on the Instagram account Sondheim Letters). The hundreds of students whose master classes and performances he attended, offering solicitous feedback. People who never met him but who pored over his books, soaking up his thoughts on structure, form, and content. People like Michael Schulman, who wrote in The New Yorker that Sondheim “taught me to be a person.”

People like me, who still do not know how to be Jews and people and artists all at the same time, but who continue to learn. Just like he taught us.

Gabrielle Hoyt (she/her) is a dramaturg, writer, and director. She is pursuing her MFA at Yale. @gabhoyt