Playwright Ed Bullins died on Nov. 13, 2021; he was 86. The following is an excerpt from Woodie King Jr.’s 2003 book The Impact of Race: Theatre and Culture.

In 1968, Ed Bullins arrived in New York City from San Francisco with about a dozen plays in his trunk. I’d read some of his articles in Negro Digest, and he’d sent me some of his plays: In the Wine Time, Clara’s Ole Man, and Goin’ a Buffalo. He’d made a commitment to playwriting: a commitment to explore the lives of Black people. His arrival signaled a change in Black theatre’s direction.

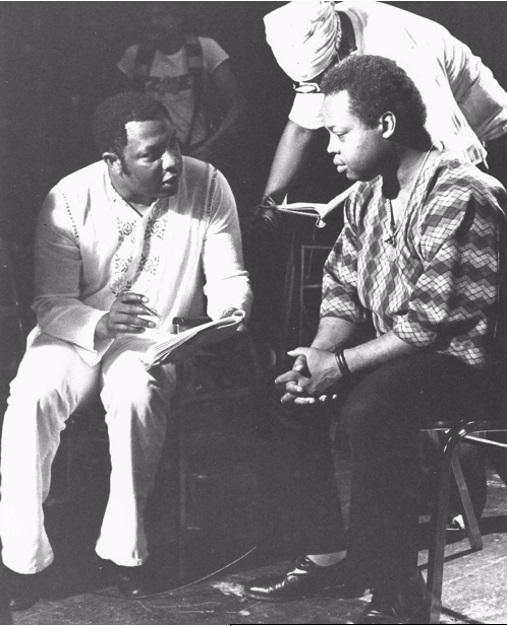

I met Ed soon after he arrived. I don’t remember exactly how we ended up that evening at my apartment on Riverside Drive. We talked late into the night. Ed said very little but he drank a lot of wine. We laughed a lot. He didn’t mention his new position at the newly formed New Lafayette Theatre. The bottom line was, I loved his plays and was totally committed to his writing.

That same week I introduced his work to Wynn Handman at American Place Theatre, which presented Bullins’s one-acts, including A Son Comes Home, Clara’s Ole Man, and Electronic Nigger. In the following years they presented his full-length plays The Pig Pen and House Party, and did a rehearsed reading of Goin’ a Buffalo. Robert Macbeth’s New Lafayette Theatre produced the landmark production of Bullins’s In the Wine Time. That production, with Sonny Jim Gaines, Gary Bolling, Bette Howard, George Miles, Kris Keiser, Bill Lathan, and the other New Lafayette players, was the most brilliantly produced and directed work in the Bullins canon; Macbeth directed it with awesome detail.

I’ve produced or directed seven of Bullins’s plays: The Gentleman Caller, In New England Winters, The Taking of Miss Janie (1974, produced with Joseph Papp); The Fabulous Miss Marie (1975, produced); Phyllis Wheatly (1976, produced with Steve Tennen); Daddy (1977, produced with Joseph Papp and directed); Salaam, Huey Salaam (1991, directed). Why did I produce and direct these plays? Why am I drawn to the plays of Ed Bullins? Without question his plays reaffirm details in Black life as I’ve come to understand it. The language and violence in his early plays, especially in Clara’s Ole Man, as well as the plays in the 20th century cycle, are so precise I could not ignore them.

In 1968, seven months after Bullins’s arrival in New York City, I produced A Black Quartet (four one-act plays by Baraka, Bullins, Caldwell, and Milner). Bullins’s The Gentleman Caller was included. This piece is an avant-garde play in the tradition of Albee, Pinter, and Beckett. However, it’s very Black in terms of language. Bullins’s exploration of new forms within the Black theatre structure resonates throughout all of his plays. Bullins is, first of all, a master craftsman.

The language and the concise Blackness of Bullins’s In New England Winters combined to take Black theatre to a level of beauty not found in the American theatre; certainly not found in Eugene O’Neill or Tennessee Williams. New Federal Theatre’s 1971 production, directed by Dick Anthony Williams, combined the violence, the language, and the characterizations of Black life. The violence of America was further explored in my production of The Taking of Miss Janie; that production was directed by Gilbert Moses and co-produced by Joseph Papp; it moved from New Federal Theatre to Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and won three Obie Awards, as well as the Drama Critic Circle Award for Best New American Play of the Season.

My production of Daddy explored this violence within the context of redemption, and a kind of reexamination of priorities. Bullins seemed to be analyzing himself as an artist and as a father. Language and character are so clear in The Fabulous Miss Marie that one leaves the theatre realizing how accurately Bullins captures the new Black middle class. The Fabulous Miss Marie and In New England Winters can take their places among the finest plays written for the Black theatre. As stated earlier, Bullins is a craftsman (though he often downplays this aspect of his work). He’s also an astute historian; never confuse his personal quietness for lack of knowledge. I listened to him in his career destroy a theatre historian in a radio discussion on Black theatre. To understand the language and characters within Black culture as well as Bullins understands we must assume he was a witness; he’s been there!

A recent anthology of plays by Ed Bullins on historical characters, edited by Dr. Ethyl Pitt Walker, gave the Black theatre much needed new work. Even though I produced one of Bullins’s historical plays, Phyllis Wheatly, I was surprised to learn from Dr. Walker the vast number of these types of plays he’d written. One forgets Ed Bullins is a playwright; a playwright writes plays. His plays are included in many of my anthologies. His work has always been integral to the Black theatre movement. Bullins has given the Black theatre anthologies, criticism, and scholarship, exploring its theories, its practices, and its aesthetics.

I often think of Bullins when I recall a speech given by Eleanor Traylor. She was speaking about James Baldwin, though she could just as easily have been speaking of Ed Bullins. Baldwin had written hundreds of articles, eight non-fiction books, 10 novels, and hundreds of speeches—a body of work on Black America any new writer must come by to be in the same league. Baldwin quoted the Bible wherein the Lord said in order to get into heaven, you must come by me. I am reminded of the vast body of work by Bullins, and warn any new playwright: You must come by Bullins!

Woodie King Jr. is the founding artistic director of the New Federal Theatre.