Jennifer Childs wanted to do a production of Henry V. Rather than a traditional concept, she wanted to create something that fit within the mission of the Philadelphia company where she serves as producing artistic director, 1812 Productions. So she started thinking about someday doing Henry V on ice, structured not in five acts but in three periods like a hockey game.

“I priced it out and it was just not even remotely feasible to do,” said Childs. “But it always kind of lived as this sort of joke in our office about how someday we’ll do Henry V on ice.”

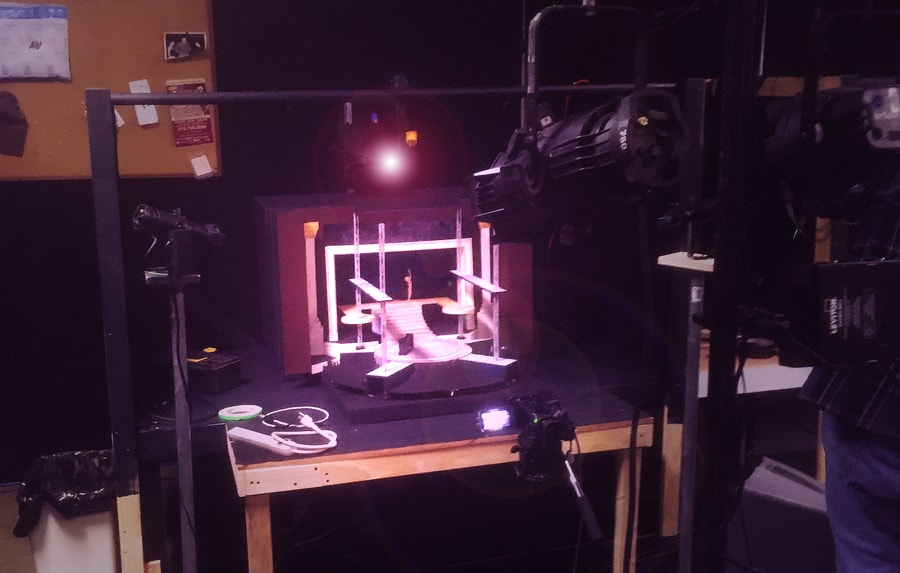

While the pandemic didn’t quite give way to her vision of an ice-skating Prince of Wales, it did spark another idea. As Childs looked around her office early on in the pandemic, cleaning up before adjusting to work from home, she noticed old set models sitting around—small-scale maquettes created by designers during the production process.

“That was sort of the beginning of this idea,” Childs recalled. “What if, during this pandemic time, we can’t make theatre life-size—what does it look like on the small scale? It kind of morphed from there.”

From there bloomed 1812’s Set Model Theatre, which (virtually) brought together 15 Philadelphia-area theatre designers to collaborate on miniature fantasy productions of King Lear. The designers were broken into three groups, assigned randomly by drawing names, consisting of a director, costume designer, scenic designer, sound designer, and lighting designer (plus help from a host of voiceover performers). The groups were then charged with creating an original approach to King Lear designed to fit inside a model-box version of Philly’s Plays and Players Theatre. With budgetary drawbacks mitigated, the groups were given different scenes and simply told that their ideas should support the text, consider relevance, and fit within the comedy theatre’s mission.

From there, each team worked remotely to create their vision as if preparing for a mainstage production. Voice actors were cast to fulfill the roles of nine characters, those actors were rehearsed (and their contributions later recorded), costumes were sketched and rendered, lighting plots were made, and sound designers created scores that incorporated both music and dialogue.

The final products from these groups would likely be enough to keep an audience entertained, watching how three different groups of designers interpreted Shakespeare’s work. Now this project, which first came together in early 2021, has been turned into a five-part documentary.

“I kept saying, ‘This is kind of like Cupcake Wars meets your graduate thesis in theatre,’” Childs joked.

The project was originally released in summer 2021, and while it got good visibility then, Childs said that she could tell that people were already beginning to feel the fatigue of watching theatre work online while outdoor activities were resuming and beckoning people back to in-person performances.

Now, with Omicron surging and theatres once again postponing or cancelling productions, the project is getting another run. And this time, thanks to the generosity of a donor, 1812 Productions is able to offer the show to audiences for free thru Feb. 7. Childs said she wants audiences to be able to watch it for a glimpse into a rarely seen part of the creative process, for those who usually only see the finished product to witness the work that goes on behind the scenes.

“We never see the designers,” Childs said from an audience perspective. “They don’t get to take their curtain call at the end of the show.”

As an artistic leader, Childs said Set Model Theatre gave her the chance to get to know more designers and enjoy their work and personalities. Many of the designers chosen for the project, Childs said, were designers who, for whatever reason, she hadn’t had a chance to work with yet. Taking the opportunity to build those relationships proved a much more fulfilling task than having her company simply go out and do something on their own.

“As it became very, very clear that our time offstage was going to extend,” Childs said, “the idea of doing one kind of jokey, one-off thing was less appealing than diving in and finding ways of working specifically with designers and recapturing some of the magic of that conception and dreaming process that you do with designers whenever you begin a new show.”

As Childs noted, for some artists, the creative process itself can be just as satisfying as enjoying the end result. She said she enjoyed being able to sit back and see the way these designers’ brains worked and to watch the creativity and inventiveness of artists thrust together on a project. Teams didn’t all work the same way; one team would start with a single idea and see it all the way through, while another would start with an idea and wind up somewhere completely different.

“You want people who are going to be down to experiment and do something crazy like this,” Childs said. “Everybody came in pretty game, but I was so thrilled by the joy with which each designer and each team approached the work.”

The challenge became the sheer amount of footage of the creative process they wound up capturing. Artists were able to provide weekly check-ins, sending in videos on what they’d been working on and some footage of their process. Despite the desire to create something akin to Cupcake Wars or Great British Bake Off, 1812 soon realized that while those popular TV shows have whole teams of people at work on them, the small theatre found itself limited by staffing and pandemic protocols.

Multifaceted theatre designer Jorge Cousineau, who has set, lighting, sound, and projection designs for dance and theatre in his background, was tasked as the production’s video designer. Before joining the project with Childs, who he’d collaborated with before, Cousineau said he’d already started to shift a bit into the video and film worlds. Set Model Theatre, he said, was originally conceived as a smaller project. But as they worked, with him charged with documenting and figuring out how to put it all together, he realized that it would actually be more like episodes of a TV show.

“We arrived at a structure that really worked well for this particular group of designers and artists,” Cousineau said, “because so much of it was found in the process of: Here’s how they work, here’s how they respond, here’s those kinds of meetings. Film traditionally is much more bound to storyboard, and the logistics behind that are much more rigid in terms of what has to happen.”

In this case, the structure of the episodes was formed as they went along and received material. Cousineau said they would sit in during production meetings as outside viewers simply there to record, then have their own meeting afterward in which themes would start to shine through.

Unfortunately, the pandemic limited the number of people who could be in the room for the final performances. Characters were puppeted by Childs and Thomas E. Shotkin, the project’s stage manager, who had to align their puppeteering with the recorded voiceovers of the actors. Apart from those two, only Set Model Theatre’s production manager, technical director, lighting designer, and videographer were able to be in the room.

“Being in the room to do the capture of each one of the final performances was the first time in close to a year that any of us had been in a room doing anything that resembled tech,” said Childs, saying that one lighting designer told her they went home and couldn’t sleep because they were so wired from the experience. “There’s a giddiness that happens in tech that is so wonderful. I left those tech sessions feeling just hugely alive. I don’t know that I realized how much I had missed that.”

As she reflected, Childs said she’d do it all again in a heartbeat. Not only did it introduce Childs to designers she’d never had a chance to work with; the process also created completely new, individually exciting projects that may inspire more. Cousineau agreed, saying that he’d be interested in another couple of seasons, featuring different groups of designers each time, since so much of the final product is determined by how the individual artists collaborate.

Plus, Childs added, online content and online engagement are very much here to stay. Sure, one of the main reasons she liked the project was because it was a way to interact and work with actors and designers alike during a tough time. But she also hopes this project can shine a light on the many different ways theatre can be shown and enjoyed online.

“It doesn’t have to be a production or a Zoom reading,” Childs said. “There are other ways of looking at a project and finding ways of making content that are still very theatrical in ways that are not necessarily a play.”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor of American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org

Creative credits: Set Model Theatre, production manager Ben Levan; technical director Lance Kniskern; video designer Jorge Cousineau; producing artistic director Jennifer Childs; stage manager Thomas E. Shotkin; original music by Willem Cousineau; directors: Tanaquil Márquez, Brett Ashley Robinson, and Suni B Rose; costume designers: Natalia de la Torre, Jill Keys, and Leigh Paradise; scenic designers: Jennifer Hiyama, Colin McIlvaine, and Sara Outing; sound designers: Elizabeth Atkinson, Damien Figueras, and Daniel Ison; lighting designers: Shon Causer, Aly Docherty, and Maria Shaplin; voice-over performers: Brian Anthony Wilson, Pax Ressler, Jaedto Israel, Anita Holland, Anthony Martinez-Briggs, Jo Vito Ramirez, Frank Jimenez, and Andrew Criss.