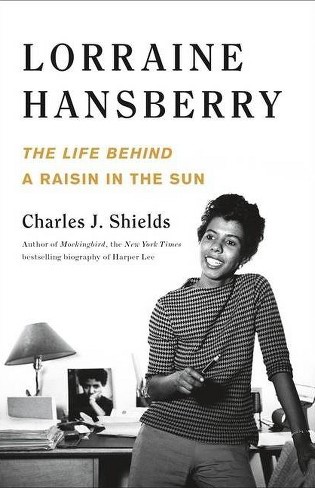

The following is excerpted from Lorraine Hansberry: The Life Behind ‘A Raisin in the Sun,’ a new biography by Charles J. Shields, published by Henry Holt and Company, New York, copyright © 2022 by Charles J. Shields. All rights reserved.

On Easter Sunday, April 6, 1958, Lorraine got up from bed sometime after one o’clock in the afternoon. Her old enemy, depression, had returned. It usually did around holidays. Added to which, Saturday had been a day of heavy celebration, with scotch, because Langston Hughes had given her permission to use a line from his poem “Harlem” as the new title of her play in progress, “The Crystal Stair.” She had been waiting to hear from him since February, when she completed the first draft. Now it could be rechristened A Raisin in the Sun.

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Where Bob Nemiroff was, she probably didn’t know. They were drifting apart as husband and wife, though they remained devoted friends. “Do have a good time. Of course I miss you,” she wrote to him when he went to San Francisco on music business. She sometimes saw him by appointment, noting the day and time in her pocket datebook. A melancholy ballad he’d written with Burt D’Lugoff, “You’re Everywhere,” was going to be recorded by Phil Rose’s Glory Records.

Outside her window, it was dark and rainy, but she got dressed and went to Prexy’s, a diner on the corner of Christopher Street and Green-wich Avenue, for an afternoon breakfast. She ordered pancakes and coffee. While she waited, she smoked and read The New York Times. A woman tried to strike up a conversation with her about travel, but Lorraine wanted to catch a 3:25 p.m. showing of Sayonara, and there were fewer trains running on Sunday. The pancakes and coffee came to 80 cents. She got to the movie theatre on time and paid 68 cents at the box-office window.

Set during the Korean War, Sayonara, starring Marlon Brando, was about a love affair in Kyoto between an American fighter pilot and a famous Japanese dancer. The scenes in the Imperial Gardens were gorgeous, splashed across the screen in 75 mm Technicolor, and Lorraine was “much moved”—something that didn’t happen very often when she went to the movies.

It was 6:30 p.m., and still gloomy and drizzling, when she came out of the theatre. The streetlights were coming on. Rather than get a bite of supper somewhere, she went home and put a dish in the oven. She turned on the radio and sat at the kitchen table. It was 7:15 p.m., and the apartment was quiet except for Spice, “the sort of collie.” She was lonely.

For about two months, she’d been meeting with Lloyd Richards on Saturday afternoons to revise her first complete draft of A Raisin in the Sun. The first act was still pretty much as she had written it during that furious birthday weekend in May almost a year before. But she was stuck, dangling somewhere in the third act with two possible endings, unsure of which one she should write toward. She imagined having the Younger family hunkered down inside their home, preparing to defend themselves against rioters, poised with bats and kitchen utensils. A sort of stop-action tableau, perhaps, then go to dark. Or maybe Walter Lee could undergo a religious conversion and see the light. Peace would reign with a larger message for humanity. But that would be the worst kind of deus ex machina. She was also unsure about using a fantasy ballet she had in mind to express the characters’ hopes.

She was fortunate to work with Richards, who later directed nearly all of August Wilson’s work on Broadway. Her collaborating with him illustrates how a dramatic work, from script to stage, becomes a palimpsest—revised, rewritten, and reinterpreted. And this was not just a development of the modern stage: It’s estimated that during London’s spring-summer theatre season of 1598, over 80 percent of the plays performed were works of collaboration.

In most literary genres, the word author is taken to mean a single person. Not so in theatre, where the director, performers, designers, and technicians challenge the creative authority of the playwright. There is no correct meaning of the text. “Ready for the stage,” Richards said, “doesn’t necessarily mean ready for an audience or ready to be a hit or ready in any other component. Ready for the stage, to me, means that there is a true line to the dramatic action in the play, that the characters are relatively clear, that they speak with an individual voice, and that they interact with one another with some degree of reality. Then they can begin to explore questions that may exist within the piece as you work on it.”

Richards was 38; Hansberry, 27. He had been born in Toronto, Canada, in 1919. When he was four, his family moved to Detroit, where his father, a Jamaican “Garveyite” master carpenter, had worked for better wages on the assembly line at Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant. After high school, Lloyd enrolled in pre-law at Wayne State University, but he fell in love with performance. When he was a teenager, he had delivered Bible readings in church in his fine, warm voice. Seeing how his college classmates responded to his rendering of a speech from Macbeth, he knew he had found his calling.

His father had died a few years earlier, and Richards’s mother was adamantly against his switching from pre-law to speech and theatre. As it happened, World War II intervened, and in 1943, Richards enlisted in the Army Air Corps, training to be a Tuskegee Airman. But before he could earn his wings, peace was declared. Returning to Detroit, he joined a troupe of student actors. They rented a large, empty house and turned the living room into a theatre-in-the-round, with concentric rows of folding chairs. They made stage lights using 300-watt lightbulbs and slipped Quaker Oats containers over them to focus the beam. His apprenticeship in community theatre lasted two years.

In 1947, he moved to New York City and lived at the YMCA at 135th Street off Lenox Ave., in Harlem. At an audition for nonprofessional actors held by the Equity Library Theatre, he met actor Paul Mann, who offered him a job as an assistant in his Actors Workshop. Richards was a dependable character actor, but he wanted to be “a meaningful storyteller,” he said, because theatre deals with things “that people are concerned about?'” He took the job.

One of his classmates was Edwin Sherin, later a television producer, who remembered that Mann’s Actors Workshop “was the place to be” in the early 1950s. Located in an old building at 43 Street and Sixth Avenue, it “was a mecca for eager, idealistic theatre professionals.” Several days every week, actors climbed four flights of dusty stairs, Sherin said, “to satisfy their craving, to do it ‘right.'” Among them were Cicely Tyson, Sidney Poitier, Hal Linden, Paul Mazursky, Faye Dunaway, Ossie Davis, Barbara Ann Teer, Ruby Dee, and Douglas Turner Ward. According to Ward, Paul Mann had “committed himself to teaching and dealing with non-majority, non-white students, without paternalism during a time when other acting teachers were just not interested in the minority students” because there weren’t enough parts for them in theatre.

One afternoon, Richards and Poitier went out for lunch together. They couldn’t each afford a hot dog, so they bought one and split it. “If I ever do a major show,” Richards recalled Poitier saying, “I’d like you to direct it.” Richards returned the compliment. Poitier would be his first choice, too, as an actor.

Several years passed. Then, in the spring of 1958, Poitier phoned Richards excitedly. “I got it—I got the play I want to do on Broadway.” He mailed a copy of the unfinished draft of A Raisin in the Sun. Richards and his wife, Barbara Davenport, a dancer in the original production of The King and I, divided the parts and began a cold reading. Despite the play’s length, which was almost four hours, they “howled, and we cried, we had a wonderful time reading it,” Richards said. “I told him I was interested.” Next, Poitier arranged for Richards to meet Phil Rose at the office of Glory Records, on West 57th Street. Rose was frank about the financial situation: There were no backers yet. But before Richards made a decision, Rose recommended that he meet the playwright, Lorraine Hansberry—hoping, probably, that Richards would want to work with her.

He met Hansberry for coffee one afternoon and they got to know each other. “And I had great respect for that woman,” Richards remembered. “We liked the same people: Chekhov, O’Casey, and Robeson, whom she had worked for.” About her play, he recalled her saying, “I’m not doing it to be the first Black anything.” A Raisin in the Sun was about her family.

His impression was that she had “felt diminished and destroyed by the real estate powers in Chicago,” and she blamed them for her father’s death. A Raisin in the Sun was her wish for her brother Perry, the more entrepreneurial of the two brothers, to have a better life than their father. Perry and Walter Lee Younger were alike, she said, because “the drive which impelled them both is the same.” (When Douglas Turner Ward later met Perry, he was “shocked,” he said. “Her brother was Walter Lee in the play!”) Walter Lee would start out convinced that a combination of making big plans, cutting corners, and getting money was the way to seize the American Dream. By the final act, Hansberry wanted him to show signs of maturing and living up to his responsibilities as a father and husband, instead of believing that money would make him a man.

Richards had the whole picture now: Hansberry was an unknown playwright; this was her first play, and it didn’t have out-of-the-box commercial appeal. Nevertheless, he agreed to direct, because getting involved didn’t pose much of a risk, really—there wasn’t a lot at stake, except his time. “It was no big deal.” Besides, he needed the experience directing.

There was another hurdle to be cleared, however, which was Hansberry’s first draft. The way she had written it, the main conflict in A Raisin in the Sun was the mother’s (Lena Younger’s) decision over how to make the best use of her late husband’s life insurance money to help the next generation. In the first act, all the characters speak to Mama Younger and then leave, clearly establishing her as the person around whom the play revolves. Gradually, Lorraine “bought into the idea,” Richards said, “that the play was really about Walter Lee Younger’s coming-of-age. Learning to deal with the past, his father, and the present, which is what he was living through. And what was being imposed on him by social circumstances.” But to switch protagonists wouldn’t be easy. The entire play would have to be restructured.

Every Saturday afternoon, they met. Lorraine would wait while Lloyd read over her pages, still fresh from the typewriter, for what had been added, eliminated, or revised. He would challenge her with new ideas, and then “she would top me in what she wrote.” They went scene by scene. During the week, she rebuilt the play, using, she said, “as a model, as a point of departure Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock.” How much of A Raisin in the Sun was Hansberry and how much Richards is unknown; the original manuscript was lost.

Charles J. Shields (he/him) is an American biographer of mid-century American novelists and writers.