From the moment Six started performances on Broadway, audiences were singing along. “Don’t Lose Your Head” and “No Way” were already well loved anthems, and even some tricky, witty turns of phrase (“You say it’s a pity ‘cause quoting Leviticus/I’ll end up kiddy-less all my life”) echoed from the house in solidarity with the fierce queens onstage.

The show hadn’t even opened yet.

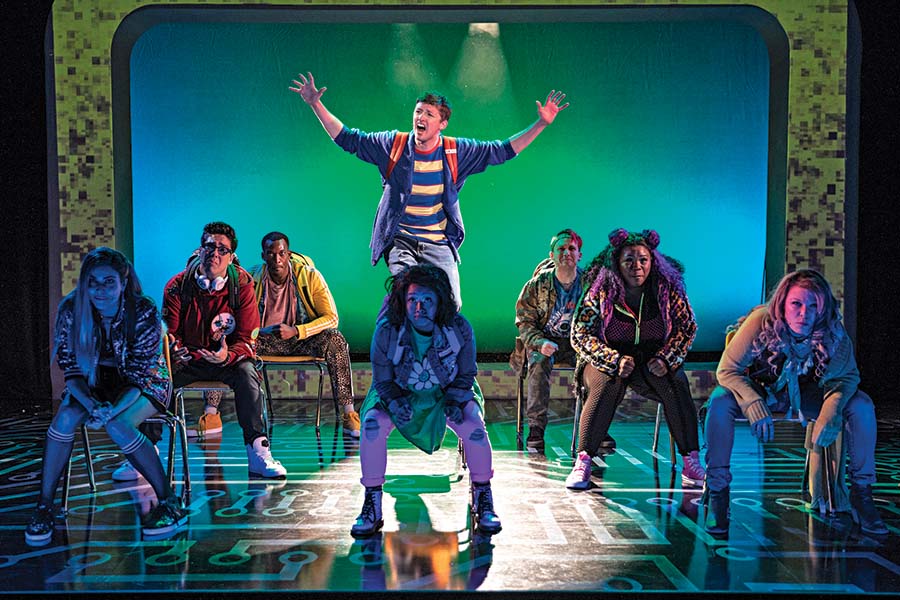

Six isn’t an outlier. One thing Hadestown, Be More Chill, and a majority of recent original Broadway musicals have had in common is a musical fan following that is large and invested well before the first preview.

This isn’t a brand new innovation. The long history of cast recordings being released ahead of a commercial production goes back to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar in 1970, and by the ’90s it had become a mainstream commercial move with the musicals of Frank Wildhorn. But with the drastically changing economics of Broadway raising the need for brand recognition to unprecedented levels, as well as the advent of technology that theoretically gives everyone with GarageBand and a mic the ability to release a quality album, it is becoming more the norm than the exception, to release music ahead of opening a show.

In the so-called Golden Age of Broadway, shows had relatively smaller budgets and could recoup faster. The most economically profitable model was to have more productions per season with shows having shorter runs. In this way, originality was rewarded—it was more viable to take a chance on a new show or writing team, as the financial risk wasn’t as great and new material was always needed.

But in the 1980s the economics of Broadway began to drastically change. With bigger, spectacle-driven productions coming to dominate the scene, the cost of producing a new musical in New York City’s commercial theatre district became astronomical. Producers could no longer hope to recoup by running months, even years in some cases. Now a hit show meant it had to last for a decade at least, as well as cultivate a market through tours, overseas productions, and merchandise. On top of this, in the early 2000s, ticket prices increased as they never had before, thanks partly to the rise of the internet and unprecedented competition between shows and scalpers.

Such high financial stakes, for both producers and audiences, raised the demand for brand recognition to new heights. This is one reason adaptations of movies, TV shows, celebrity autobiographies, and song catalogue/jukebox musicals have made up a majority of new shows in recent years.

What’s an original musical to do?

Van Dean (he/him), Tony- and Grammy-winning producer and president/co-founder of Broadway Records, a label dedicated to original cast albums, doesn’t see a problem with the predominance of brand recognition.

“If someone is going to spend $100 to $200 per ticket for a Broadway show, they like to have some assurance that they will like what they are about to see,” Dean reasoned. “There is so much to take in—story, performances, lighting, scenic design, costumes, orchestrations, etc.–that knowing the basic story and the songs going in allows you to fully appreciate all of those elements.”

Indeed, it’s probable that Hamilton‘s streaming album release on NPR’s website in 2015 helped many outside of the range of its New York run learn and begin to process this show’s rapid-fire pace long before the show was widely available on Disney+. Broadway composer Joe Iconis (he/him) also enjoyed great success with the early release of the cast album for his show Be More Chill. But he’s concerned about the overarching trend towards commercial brand recognition on Broadway.

“I think the idea of ‘you already know, you’re gonna love it’ is murdering theatre,” said Iconis bluntly. “People are getting more and more conditioned to only see musicals that they already are familiar with. I would love it if the general public would come to see a musical not based on a pre-existing property with a sense of curiosity and wonder, but that’s just not where we’re at.”

Broadway Records has been at the forefront of releasing cast albums, including Matilda and Wildhorn’s Bonnie and Clyde, many of them ahead of their commercial opening. Dean pointed to creative as well as commercial benefits to this trend, including the potential for the act of creating an album to focus writers’ thoughts on how they initially present their songs—the arrangements, the orchestrations, the casting—which in turn can help potential backers, theatres, and producers understand the creators’ vision.

“I would strongly encourage releasing an album as a promotional tool for shows in somewhat earlier stages of their production timeline, to help the writers get their shows where they want them to go,” Dean said. “However, if there is already a producing team ready to take the show to Off-Broadway, Broadway, or West End production, a concept recording would be less necessary, and it would be better to wait to produce the full cast recording.”

“This review stopped all New York theatres and producers from being interested in Be More Chill, but Two River made a cast album anyway, so the show could live on in that way.”

Broadway composer Frank Wildhorn (he/him) paved the way for early album release as a common practice. Wildhorn came to the theatre world from the perspective of being a “pop guy,” as he’d written, produced, and sold tens of millions of records before his first show ever came to the Great White Way.

“I absolutely 100 percent stole the idea from Andrew Lloyd Webber,” Wildhorn admitted. But he’s taken it up a notch: He’s known for creating multiple albums of his shows, so it is possible for the public to hear most of his shows in varied forms, giving fans insight into the development process.

“In the early ’90s, I created Atlantic Theatre, a division of Atlantic Records,” Wildhorn continued. “During those years, we made two Jekyll and Hyde albums, two Scarlet Pimpernel albums, two Civil War albums, and many Linda Eder albums. They were all wonderful calling cards for the shows, and they involved mainstream artists. It’s always worked, and I’m continually doing them, even today.”

Wildhorn pointed out the difference between a concept album (sometimes called a studio recording) and a cast album. A concept album is generally agreed to refer to a stand-alone recording of songs tied together by a loose theme, which may or may not be guided by the impulse to turn the album into a musical, and which often involve vocalists who have nothing to do with performing the work onstage. The Who’s Tommy and American Idiot, for instance, were created as rock albums with a loose connective thread—threads that were later elaborated and woven together by theatremakers for Broadway adaptations. A cast recording, on the other hand, is traditionally a snapshot of a show as it exists onstage. But it’s interesting to note that Lin-Manuel Miranda’s original idea for Hamilton was simply to create a stand-alone concept album, The Hamilton Mixtape (also the title of a 2016 compilation of pop and hip-hop artists interpreting songs from the hit show).

Of course, some projects fall into a grey area. For example, because of the pop-folk style of the score, the original production of Pippin wanted its cast album to function more in the pop world, so they specifically recorded their album to be less a snapshot of the show and more a stand-alone pop record. For other productions, as theatre historian and Be More Chill producer Jennifer Ashley Tepper (she/her) noted, releasing an album early can dramatically alter the trajectory of a show.

In 2015, Tepper recalled, Be More Chill had a short run at Two River Theater that received a negative review in The New York Times.

“This review stopped all New York theatres and producers from being interested in Be More Chill,” Tepper said, “but Two River made a cast album with Ghostlight Records anyway, so the show could live on in that way.”

Shortly after that, she helped produce a concert version of Be More Chill at Feinstein’s/54 Below, where Tepper is the creative and programming director. It was then that the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization decided they would license the show.

“When the album unexpectedly started gaining a huge following,” Tepper said, “and the licensed productions began experiencing this fandom as well, there was suddenly the opportunity for the show to come to New York, to Off-Broadway and then Broadway. The album was what gave the ability for Be More Chill to come to New York when the traditional path didn’t.”

Added Iconis, “Be More Chill is authentically itself and was made by actual human beings who just wanted to make the best musical possible. It wasn’t a show that came to life because a corporation wanted to further exploit the brand of a title they owned. We didn’t even have a commercial producer attached to the show when the album was made—we got a commercial producer because of our insane fanbase years later. It’s pretty wild. Because of the types of shows I write and because of the place I hold in the industry, I don’t have the luxury of letting the show come before the album.”

Six producer Kenny Wax (he/him) also had a positive, albeit very different, experience with an early album release. As Wax explained, the Six studio album was recorded before the show opened. Since the show was picked up as a student production, they wanted to hear what it sounded like with a professional cast. Six performed one week at the Cambridge Arts Theatre, one week at the Norwich Playhouse, and then performed on a 400-seat upturned inflatable purple cow at the Edinburgh Festival, around which time the album was released. Wax added that he has no doubt that the studio album was a main driver of the show’s runaway success early on.

“We understood our audience demographic and wanted to seed the music into the wider pop listening community,” Wax said. “There is no way that we could have got such engagement from the public so quickly with the very few numbers of people who were seeing the show live. We wanted the audience to come to the show from both directions, from hearing the album and from watching a live performance. But my guess is that the number was 1000 to 1 in terms of reach between awareness of the album and show audiences.”

On the flip side, once a show has found success, not having an album that accurately reflects the license-able version can be a hindrance.

“Since so many people come to learn shows from their cast albums, and that is how they exist in perpetuity no matter what phase a show is in as far as its New York run, having the album and the finished show that is performed and will be licensed have differences is in no one’s best interest,” Tepper said. “If an album takes off before a show gets a major run, I think there is a balance that the creators seek to maintain, of developing the show as needed but also staying true to what fans are already familiar with on the album. But in general, this is one of the main reasons that shows which do have a planned trajectory may not want to release albums before the show is in its most finished state.”

Wax differs slightly (“250 million streams and counting would tell us that it doesn’t” matter if there are differences between the recording and various stagings of Six), but then Six may be a unique property in this space. The original studio album is currently the only recording of Six, and is sold at every production around the world regardless of the fact that most audiences will not see any of the performers featured on the album onstage, and that there have been tweaks to the score since the recording was made. But the producers have “always intended to do an actual cast album incorporating everything. That’s very much in our current plans.” One imagines that rabid fans will snap up that version as well.

One question this new paradigm raises: Will this change how composers write for musical theatre? With the rising need for songs that work in a pop arena out of context, will there be a move away from scores where the primary musical goal is to advance the story? Is this a new challenge—or a retread of an old one? After all, in Broadway’s so-called Golden Age, one of the composer’s main goals was to create hits for music publishers and to have chart hits made by pop singers of the day. Songs like Rodgers and Hart’s “The Lady is a Tramp,” to cite just one example, had a million reprises, and worked out of context for a reason. The difference is that in those days it was largely the show selling the music. Now it’s the other way around.

Wildhorn is understandably bullish on the trend, believing that cast albums can make a “total visceral” connection with audiences that can only benefit the live experience. “When the music or a show hits a nerve,” he said, “it becomes a way to preserve memories that people love. We’re all nostalgic. It’s a magical thing that happens.”

In the end, does it matter which comes first, as long as both the records and the shows keep coming?

Ashley Griffin (she/her) is a performer and writer with Broadway and Off-Broadway credits, as well as TV and film. Her work has been produced/developed at New World Stages, Manhattan Theater Club, and Playwrights Horizons, and she has taught at NYU.