The following is the afterword to a new edition of Ruhl’s 2003 play Eurydice (TCG Books), which has just been adapted into an opera with composer Matthew Aucoin, currently at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera through Dec. 16.

“Am I allowed to ask my book/whether it’s true I wrote it?’—Pablo Neruda, The book of questions

i.

After 20 years, it is difficult to ask questions of a play you once wrote, and difficult for the play to answer. Am I the same person who wrote Eurydice, if there ever was such a person? Still, I feel compelled to ask her some questions; mainly, the questions I have been time again asked by actors, designers, audience members, directors, and students. It seems only compassionate to answer them in print. These questions, mind you, are not the most important ones to ask of the play, but because they seem to be repetitively mysterious, I wanted to be of service.

- Are the directions the father speaks near the end of the play directions to a real place?

Yes, these directions take you to a house in Davenport, Iowa, where my grandparents lived, on 111 McLellan Blvd. They don’t live there anymore. But you’re welcome to follow the directions and say hello to the house from the road. In my imagination, a final act of forgetting involves a final act of going home. I found a scrap of these directions written out to me, by my father, in my desk, while I was writing the play. My father died of cancer when I was 20, and I was very close with him. Much of the play was inspired by the attempt to have more conversations with him. Now the grief in this play belongs to other people—those who read or embody the play.

2. Did Eurydice really have a father who she met in the underworld?

No. We know so little about Eurydice, we only have scraps from Virgil and Ovid. We know so much more about Orpheus, and even he is mysterious. But in my imagination, it stood to reason that Eurydice would meet an ancestor when she reached the underworld; in this case, her father.

3. Why are Eurydice and Orpheus dressed in 1950s bathing suits in the first scene?

That is probably the question I am asked more than any other question. Other than torturing the actors, the reason I pictured Orpheus and Eurydice in vintage swimming trunks was that I wanted to conjure the feeling of memory, without actually setting the play in the 1950s, or in the distant past. I did not want the play set in ancient Greek times because I did not want the opacity that such distance can create, but I also did not want to set the play precisely today.

The feeling of memory is often associated with our grandparent’s generation (one step removed). For me, that generation wore pink traveling coats to elope or die in. For others, memory might look very different, and I welcome other interpretations. If Orpheus and Eurydice were people who lived today, they might be young artists without much money who love vintage clothing, and you might find them rummaging around in the Salvation Army or in their grandparents’ closets, to find a particular traveling suit.

4. How do you costume the stones?

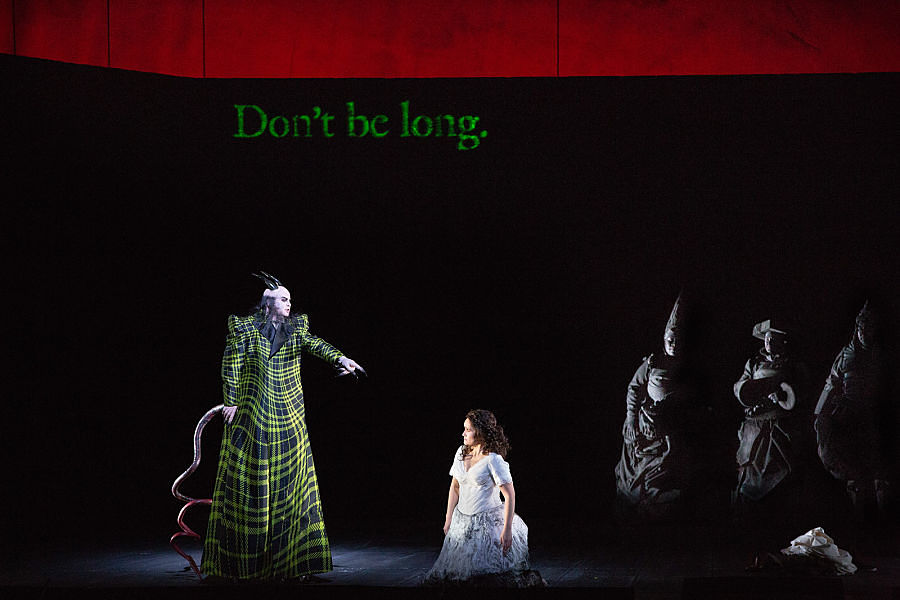

When I wrote the play, I imagined that the stones might literally be three little rocks onstage with light shining on them, voiced through a microphone behind the curtain. But when I first staged the play, it seemed far more theatrical and interesting to have live actors moving around and speaking rather than pebbles lit up. The stones enforce the rules of the underworld, amuse us when things are going very badly, and are immovable beings who are ultimately moved to tears by music. How a director conceives of the stones is, I think, the secret code of a whole production—they, in a way, create the world, and I have seen the stones enlivened in so many ways.

In Les Waters’s iconic production, the stones were ossified Victorians wearing grey encrusted clothing; they even wore eye contacts to render their irises colorless. I’ve seen the stones as lifeguards, as Kabuki dancers, as children, as old people. The director Daniel Fish once duct-taped the actors who played the stones to a couch, and they were costumed as teenaged slackers. In Germany, for some reason, the stones flew. It always makes me happy to see a new interpretation of the stones.

5. Does Orpheus die at the end when he comes down to the underworld?

I prefer not to know. I prefer to know only that he is, in the end, once again, dead. And that this time, he is without his music. He may have lived to an old age, but in quantum time, his old age is only a blink in time down in the underworld; he may have died by his own hand to find his beloved; he may have been torn apart by Maenads who were furious that he wouldn’t love them back (as in one Greek version). Beyond the fact of how he died, the tragedy is that he died, and can no longer recognize Eurydice.

6. What texts inspired the play?

Beyond the text of my own life (as I said, the play is quite personal), I was inspired by Virgil, Ovid, Cocteau, Mary Zimmerman’s Metamorphoses, Rilke, and H. D. Very few of the treatments of the Orpheus myth center the view of Eurydice. One of the few pieces of art by a man that imagines Eurydice’s consciousness is a poem by Rilke, “Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes.” Rilke writes:

She was no longer that woman with blue eyes

Who once had echoed through the poet’s songs

No longer the wide couch’s scent and island

And that man’s property no longer.

She was already loosened like long hair,

Poured out like fallen rain,

Shared like a limitless supply.

She was already root.

And when, abruptly,

The god put out his hand to stop her, saying,

With sorrow in his voice: He has turned around—,

She could not understand, and softly answered

Who?

Another poem that gave me substance and inspiration while writing Eurydice was by H. D. (a.k.a. Hilda Doolittle, the imagist poet). She writes from Eurydice’s voice in her poem “Eurydice”:

So you have swept me back…

So for your arrogance

I am broken at last

I who had lived unconscious

who was almost forgot;

if you had let me wait

I had grown from listlessness

into peace,

if you had let me rest with the dead,

I had forgot you

and the past…

At least I have the flowers of myself,

and my thoughts,

no god can take that…

7. You mentioned Mary Zimmerman. Didn’t she just direct an opera version of Eurydice, and what was it like to make the play into an opera?

Yes, by extraordinary synchronicity, Mary directed the premiere of Eurydice, the opera. I’ll never forget the image of Orpheus turning around in her Lookingglass production in Chicago (she and I are both from Chicago and drank the same theatrical water there) and how she used repetition so that the audience saw that gesture over and over again.

By a stroke of good fortune, we collaborated on the opera together with Matt Aucoin, the extraordinary composer, who, funnily enough, was the same age when he started writing the opera as I was when I started writing the play (25.) The process of making the play into a libretto was one of distillation, with effort and grace. It takes longer to sing a line than to say a line. So the main difference between the libretto and the play is that, though the libretto is shorter in terms of pages, it is longer in terms of duration on the stage.

Occasionally I changed a line from the original and resorted to rhyme. Or I changed a word to make a vowel more singable. Serendipitously, the play was already written with a chorus, and structured in three Movements. (A sample of the libretto and a snapshot of the hand-written score is included in the appendix to the new edition.)

8. Did Eurydice mean to say Orpheus’s name?

Do we mean to trip? Do we mean to call out when we are curious or startled? Do we mean to undo everything with a word or a gesture? Yes and no—it is the endless ambiguity in Orpheus’s gesture that makes an artist reinterpret the myth every year or so.

9. Do you need a lot of money to produce this play in terms of spectacle?

No. One thing I love about seeing a range of productions of Eurydice is how the play can be done with utter simplicity in a backyard, under a tree out of doors (one of my favorite productions was directed by Davis McCallum under a tree at Vassar), or in a black box, or in a theatre that can make an elevator come down from the grid with rain.

I remember when I did the first workshop production of the play at Brown University, some young Rhode Island School of Design students were working on the set. They were engineering students, and after they read the play, they looked very worried, and said they thought they could make a raining elevator in the tiny black box, but just didn’t have the funds. I said that we didn’t really need a real elevator, we only needed a light cue and the sound of rain. Or possibly a bucket of water that went through a sieve. “Oh!!!!” they said.

In another one of my favorite productions, the river of forgetfulness was simply an old bathtub. (That was Jessica Thebus/Sandy Shinner’s production at Victory Gardens.) In another beautiful production, at UCSD (directed by Daniel Fish), 100 empty water bubblers were stacked on top of one another to make a glowing blue wall, and stagehands pulled a cord and the wall of water bottles all came tumbling down with an enormous crash when Eurydice fell into the underworld. In one of the most beautiful lighting cues I have ever seen, a blue wall was revealed to be a wall of letters that the father had written to Eurydice over time (this was Scott Bradley’s set and Russell Champa’s lighting cue, directed by Les Waters). In another gorgeous design (Mimi Lien’s at the Wilma Theater, directed by Blanka Zizka), the string room was held aloft with helium balloons. In each case, a bathtub, water bottles, paper illuminated with light, balloons—the materials were very easy to obtain.

I love it when the poverty of the theatre stretches the imagination. Sometimes a bloated budget creates a very skinny imagination in the theatre. But I have also loved the epic scale of Dan Ostling’s design at the Metropolitan Opera, which has a far bigger budget than the one he also designed at Victory Gardens, which was little more than a bathtub.

Maria Dizzia, who played Eurydice in the Berkeley/New Haven/New York premiere, once told me in a moment of vulnerability: “There are no pillars to hide behind.” She meant the set (there were no pillars, no props, nothing to fiddle with on stage), but also that the language was bare. I love her notion—maybe we should all aspire to it—not hiding behind pillars.

10. And have you ever been in love with a musician?

Yes. Haven’t you?

ii.

I said earlier that the questions I am posing to myself aren’t necessarily the most important ones to pose when approaching this play, either as a collaborator or as a reader (and aren’t all the best readers really collaborators?).

Some Important Questions you might ask of yourself while reading the play:

- Who have you lost and what would you say to them if you suddenly found you could have more conversations with them?

- Who would win in a battle between language and music, and does there need to be a battle?

- What is your vision of the afterlife?

- When you lost the person you loved, did it make a sound? Was it sudden? Seen or unseen? Over a long period of time, or in a single moment?

- Could you freely give a person you love to another person’s love, if you could not be with them?

- What memories would you keep if you could hide some inside of rain?

- Who or what would be your own personal Hades?

- How can we show improvised care for someone we love, even if all we have on earth is a ball of string?

- How can we mourn in the theatre, and what is the proper place for ghosts?

- Are we our memories, or something else?

I want to end this volume with gratitude for all of the people who have embodied these roles, and designed temporary worlds for this language. I think all great theatre is the meeting of this triad: actor, ether, and language. The language in these pages would be incomplete without the ether that a company creates through the bodies of brave and magical actors.

In some ways the theatre is a kind of incarnation. Unlike the film world, which takes an actor’s body and turns it into image, the theatre world takes language and makes it live with the body of an actor. And that same language can be alive, in the present tense, every time it is performed with a new voice. I’ve never seen a more thrilling magic trick.

Thank you to all of you who have embodied these words.

Sarah Ruhl, Evanston, Ill., July, 2021