A little over a century ago, the Moscow Art Theatre toured to the United States and kicked off a revolution in how Americans approach acting and the teaching of it. Few in that revolution were as central as Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner, two friends, and actors with the Group Theatre, who would base their multi-decade teaching career on the ideas and teachings of the Moscow Art Theatre’s founder, Konstantin Stanislavski. Besides teaching some of the most famous and important actors of the 20th century between—a list that includes Marlon Brando, Joanne Woodward, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, and Harvey Keitel— Adler, Meisner, and Group Theatre co-founder Lee Strasberg ushered in a new kind of American acting that was more vital, vibrant, immediate, and naturalistic than what had come before. If you’ve ever used the word objective when working on a scene, done an acting exercise involving repetition, broken a scene down into beats, or recreated your morning routine at the mirror in acting class, you have worked within this lineage.

Observers have been predicting the death of Stanislavski-based acting instruction since at least the early 1960s. Adler and Meisner even joined the doomsayers in the late 1970s as they contemplated their own mortality in the pages of The New York Times. Yet Stanislavski-based pedagogy has persevered, as have the Stella Adler Studio and the Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre, the schools from which Adler and Meisner taught generations of actors. As the author of the forthcoming book The Method: How the 20th Century Learned to Act, I was curious to learn how these schools have managed to reinvent themselves for the 21st century, and in particular how they see the future of acting in a fertile but fractured media landscape, and are preparing their students to be a part of it.

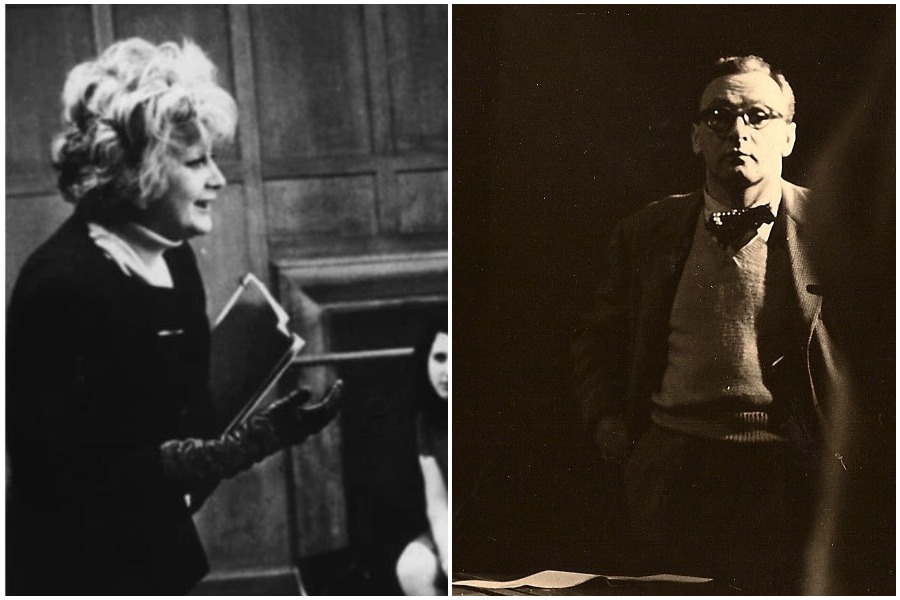

To find out, I spoke over Zoom with Stella Adler Studio’s artistic director and president Tom Oppenheim, and Pamela Kareman, the executive director of the Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre. Both had deep connections to their schools prior to taking them over: Oppenheim not only studied with Stella Adler, he is her grandson; and Kareman studied with Meisner in the 1970s and remained close with him over the final 20 years of his life. Both were eager to meet one another, if only virtually, and gracious and thoughtful in their responses. Our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, touched on the challenges of teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, how their school’s missions have and have not changed, how increased diversity has shifted some of their practices, and what the future might hold for the ideas of Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner.

ISAAC BUTLER: In 1979, The New York Times interviewed both Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner for a piece, and both were quite skeptical about the prospects for Stanislavski-based acting instruction after their deaths. Stella said, “Since, in general, there is no heritage in the American theatre, you have no real taking over from the master teacher that will provide continuation of the Stanislavsky system,” and Sandy said, “The Stanislavsky Method as a collective movement guided by teachers of vision is clearly on the way out.” Yet here we are, decades after both teachers have passed away. Your schools are still here, and Stanislavski is still the cornerstone of much of American acting instruction. How did your institutions weather that transition into the post-Great Genius era?

PAMELA KAREMAN: Many of the teachers, especially in the Meisner technique classes, knew Mr. Meisner and studied with him. I knew him pretty well, but I wasn’t here when he died, I was having my career and directing plays and having kids. It’s a huge responsibility to hold on to and honor the teaching and the legacy but not get too wrapped up in kissing the robe of Mr. Meisner or Mr. Strasberg or Stella, or anyone. So much time has gone on, and one must let go of the man and hold onto and honor the teaching and let it grow and not become some kind of cult.

This used to be a very male-oriented technique. There were no women in the Neighborhood Playhouse teaching Meisner technique for a very long time. I don’t know why. But I’ve changed that big time, and I always felt that was important. You have to be willing to change and you have to move forward. Technique is a living thing, and both Adler and Meisner’s techniques are about being alive and in the moment. So that’s what I cherish.

TOM OPPENHEIM: When I took over the Stella Adler Studio, I really felt concerned about what Pam was talking about— the metaphor I use is the studio turning into a wax museum devoted to Stella. I would describe what I did in sort of provocative terms: We relinquished dogma, and the letter of Adlerian Law, in favor of what I would describe as the spirit as I understood it, which is that growth as an actor and growth as a human being are synonymous. If I boiled down everything Stella believed, it was to elevate actors into the full breadth of their humanity, in order to create a theatre that would elevate an audience to the full breadth of its humanity. So we have faculty who have worked with Stella directly. We’re not running away from her technique, but we embrace a conservatory that includes people who haven’t studied with her and approaches that are not directly rooted in her, as long as the teacher upholds that spirit. The mission that we’ve articulated, based on the idea of growth as an actor and growth as a human being synonymous, is to create an environment that nurtures theatre artists and audiences so that they value humanity, while bringing art and education to the community.

Fast-forwarding to the present, we are sort of emerging from the pandemic. Most of us were remote last year. How has this affected your acting training and how you do your job?

OPPENHEIM: It may have had a profound effect on us. We closed on March 10, 2020 and trained via remote channels like Zoom. And then our reopening date kept getting pushed back and pushed back. Our summer program that first summer had between a third and a half of the enrollment we expected. We were fully remote in the fall of 2020, and then there was a partial iteration where we could let four students in a room with a teacher last spring. On the idealistic side, it meant we had to go back and read The Fervent Years and remember that all of this began smack in the teeth of the Great Depression. Life must go on. Theatre must go on, so we found meaningful ways of doing that online, including Zoom productions, which turned out to be surprisingly effective. Now we’re back in person with masks and vaccines and safety rules.

KAREMAN: We have a significant number of international students, so the first few weeks were about caring for those poor souls who were terrified and trapped in New York and not from here. We qualify for Title IV funding and have financial aid and are part of the National Association of Schools in the Theater, so we couldn’t just close the school; we had enormous amounts of money and training we were responsible for. You can’t just say, “Oh, read a book and do exercises at home,” to make up for the time the students have missed. But it was astonishingly successful. We finished the year and had a graduation online. We refurbished our building. We did the summer 2021 again online, and now we are in person. We have a mask mandate and mandated vaccines. Our students have lived through this global pandemic, and they’re going to have a lot to bring to their work as a result of it.

One major change from the 1960s to today is that it is now essentially impossible to make a living solely as a stage actor. TV and film have always paid better, but with peak TV and literally hundreds of scripted shows, there is much more work, and you don’t even always have to leave New York to take it. So is theatre still the fundamental basis of your training, or has the decline of real wages in theatre and the growth of TV and film decentered the stage at conservatories now?

OPPENHEIM: It’s changed. We offer on-camera classes. But the primary instrument is the stage. The big questions about oneself and the world and the character—the operating table is still the stage. But there’s also been an alteration in consciousness by virtue of Zoom. I think it isn’t going away; I think this technology will grow and will be utilized. When we first got on Zoom, I was like, “This is the transistor radio!” Things change and will continue to change, but at the core of the art are our huge life questions, and it feels to me that those questions will always require the stage and the techniques that unfurl most easily in person. Pamela, what is your response?

KAREMAN: I will say that many of our alumni and yours as well—I mean, think about Marlon Brando, who was a huge movie star. He left the stage at a very young age. Steve McQueen went to our school; Robert Duvall, one of our most extraordinary actors, I don’t know the last time he was on the stage. TV and film have always been there. One time I said to Mr. Meisner, “Sandy, people are always talking about, ‘We don’t do film acting,’ but what about film acting versus stage acting?” And he said to me, “Pamela, there are two kinds of acting: Good and bad. And we teach good.” (Laughs.) I think that’s true still today. I desperately want our students to make a living, because I don’t want them to be filled with despair and quit, and there’s this five-year period when they finish the conservatory where something has to happen so that they can believe that they can put bread on the table. So we do more today to help them get started in the business than ever was done in my day.

Where I teach, at the New School’s drama department, one of the things that’s changed post-#MeToo is the institution of some new rules around intimacy in coursework and acting scenes and rehearsals. So, for example, if it’s a scene study class, you don’t really kiss anymore; instead you create a gesture that symbolizes kissing. I guess now with the pandemic no one is kissing, but I’m wondering how the last few years have impacted how you do physical intimacy in the programs.

OPPENHEIM: Yes, that has affected our work. For quite a while we’ve had a contract or agreement form that actors who are entering into a scene fill out with what they’re comfortable with and what they’re not comfortable with. It’s signed off on and shared with each other and the teacher. That’s been in place for quite a while. So we don’t have any rules like the one you mentioned at the New School here at the moment, but we’re involved in conversations with faculty about introducing intimacy techniques.

KAREMAN: I’ll tell you, I started a policy even in my private class years and years ago that you can’t touch the other actor during an exercise. Because the work is so spontaneous, so improvisational. In the very beginning you’re teaching an actor to get in touch with and listen to his or her instincts and to act on them and let them guide them and not inhibit them. So I said there’s no touching at all, because you might be so angry that you might actually slap somebody, and I want everyone to feel enormously safe so you can take risks. Now if you have an impulse that might turn into a slap, you can stamp your foot and scream and yell, but you can’t touch the other actor. That’s been in place a long time and helps people to rechannel that impulse. You’re free to have the same impulse and emotion, but you’re not free to just throw a chair into a wall. In the old days there were a lot of holes in the wall, right?

When it comes to intimacy, we don’t have formal rules and regulations and we don’t have a form, although I like that idea! We have a discussion about what you’re comfortable or not comfortable with. I’m going back to the old days again: It wasn’t that there was abuse, but, you know, I’m a woman. You put up with a lot of garbage that was called teaching from some people—you know, they pinch your ass and you’re supposed to respond to that. None of that happens anymore.

One major challenge to Stanislavski-based training over the past couple of decades has to do with its roots in authenticity and capital-t Truth. There’s an argument that those ideas of what truth and authenticity are—or look like—are rooted in the male gaze, in the white gaze, and that as programs become more diverse it becomes more of a challenge to evaluate what’s really “authentic.” I was just wondering if that’s something you’ve talked about within your program, because it’s a critique I hear quite a bit.

(Pause.)

KAREMAN: Well, go ahead, Tom.

(Laughter.)

OPPENHEIM: I was just writing down your question, because that’s not a critique I’ve heard. I’ve heard a critique of traditional standards that maybe relates to that perspective. The truth as it presents itself through acting—I’ve just never seen that change in substance and quality, with respect to the gender identification or ethnicity of the actor. The Stanislavski or Meisner or Adler techniques are not about standardized behavior. As I understand them, they open the door to profound individuality and eccentricity.

Right, standardized behavior is what they were rebelling against.

OPPENHEIM: Yeah. And you see that over and over in characters as written in great plays from whatever kind of playwright: They are often great because they both crave an absolutely unique human being that can only come about through a specific actor, and they have a kind of universal relevance. I saw Pass Over on Sunday and I see it in that play. We created a program we run in partnership with the Billie Holiday Theatre called the Black Arts Intensive, and the people I watched in it, like Stephen McKinley Henderson, Phylicia Rashad—there’s no discontinuity in terms of what they were trying to facilitate and my understanding of what Stella or Sandy or Konstantin were doing.

KAREMAN: I’m trying so hard all the time to open up to the fluidity of the young people and the culture. I’m probably the oldest one here, and I find it new and different and exciting. We want an actor to find his or her or their truth, which is individual, individual, individual. You are who you are, but I do see that who you are is influenced in conscious and unconscious ways by what you’re talking about, Isaac. As a woman, I get that; I have to see that in myself.

I brought in a facilitator, a man named Yao. We’re a very intimate and small place, so I knew we needed guidance and help. He is from a therapeutic background. He brings a lot of that to his work about diversity and gender, and we have had these incredible meetings—we started with the faculty and we’ve moved on to the students now. It’s like group therapy for the Playhouse, and pretty astonishing.

A couple of years ago, I gave a scene to someone, it was one of these canonical scenes at The Playhouse where, you know, the woman rarely even has a job. There are so many scenes about housewives or young women needing money for an abortion. I’m not making light of either situation, but young women today have grown up in a different world, and that’s good. When the gal did this particular scene, it ended up being almost a comedy. The original scene was not a comedy, but because of her sensibility and strong point of view, it became one.

Along those lines, do you find yourself rethinking what you assign because your classes are far more diverse now?

KAREMAN: Yes. We’re not going to throw the past out the window or anything, but we explore the way we tell stories, and everyone’s story is so important. Everyone has to have a seat at the feast. But we don’t do material just because it’s diverse. We want to do profoundly deep and moving material, we want to train their instrument to play lead roles, and demanding roles, so it’s a lifelong course for me to read and read and read and learn and learn and learn. I welcome it.

You were nodding pretty emphatically there, Tom.

OPPENHEIM: We’ve expanded the vocabulary of a number of different playwrights that we work with in our programs and our student programs. At the same time, Chekhov is great, and there’s something there for all of us, for everyone. You want actors to be able to move around in time, and just as you want actors to go to film and bring stuff back to the theatre, the energy of what contemporary playwrights and actors bring to the classics is important and illuminating.

Changing gears a little bit, neither of your programs are “Method” programs, in the sense of dealing with affective memory or emotional recall. But still, in any acting or art-making process built upon the self, the issue of trauma is going to come up. How do we deal with our own trauma? And how do we handle material that is potentially traumatizing as actors? I’m wondering how you think through and approach those things in your schools.

(Pause.)

OPPENHEIM: Pamela—did you want to go first?

(Laughter.)

KAREMAN: All right! These young people engage so fully and they bring their trauma in a way we never did. We didn’t talk about our lives or what happened to us in our work. We went to therapy. So it’s an important movement. I mean, life is a trauma. We’ve all been through trauma. This has been the most traumatic year of all of our lives. Trauma and drama are twins; you can’t have one without the other. But if a student has a scene that has cancer in it, and says, “I don’t want to do this because we have cancer in our family,” you say, “Okay, we’ll pick another scene.” I’m not remotely going to put anyone in an uncomfortable position. Where you can see the empowerment is that they’re now saying it in the first place.

Whereas in the old days they’d just do it and feel terrible about it?

KAREMAN: They would do it and they would be a little out of touch. Sometimes the things that trigger us are not as conscious and knowable, right? You walk down the street and smelled something that sent you somewhere and you had to sit down.

That’s how Richard Boleslavsky taught people affective memory! You experience that and then write it down in a notebook.

KAREMAN: And we were not always so aware. We can talk about it now. Another reason I brought Yao on board is that he’s working with the students to not turn the heat up on hot water, do you know what I mean? If you come and say, “I need help,” we help you find a way, or get a therapist, or get the help you need. Because you have to feel free and you have to feel safe. I feel like a novice at this, because I was from the “snap out of it” generation. And I don’t think that’s right. Even during the pandemic, at first I was like, “We gotta fix this, let’s go, let’s get moving,” and then I realized, “Oh wait, let’s get a therapist in to talk to the students.” I’m curious what you think, Tom, because you know, trauma is life. Birth trauma is where it begins!

OPPENHEIM: Totally right. I appreciate you going first, Pamela. One thing we encounter in young people—and at this time it’s very positive—is increased sensitivity and awareness, and that should be honored. Theatre does have a role to play in relationship to trauma. I’ve always thought of actors as people who have a taste for engaging in these deeper, darker aspects of life, and absolutely need to live close to and dance at the edge of the precipice, so to speak. We come and watch and are blessed thereby. We are comforted. And so what Pamela is describing describes the complexity of it from my point of view as well. The primordial purpose of theatre must be served, so how best do we do that?

KAREMAN: Mr. Meisner had a quote that people love that I used to have on my wall. He said, “Life beats down and crushes our souls. And the theatre reminds us that we have one.” I think that speaks very much to what you were saying, Tom.

OPPENHEIM: Yeah. I always thought of that quote as Stella!

KAREMAN: Is it? I mean—

OPPENHEIM: It’s probably a Group Theatre thing.

There’s been a lot of rethinking of structures and institutions over the last couple of years, particularly after the start of the pandemic and the protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. We’re all asking, what are we even coming back to and what do we want it to be? I’m wondering what your hopes are for the future. What do you want to change as we transition to the future?

OPPENHEIM: My goal for the Studio is to transform it into the Stella Adler Center for the Arts, a kind of cultural center that’s wrapped around a lab theater and the studio. That was pre-pandemic, and it remains so during the pandemic. We have something called the Arts Justice Division, which is passionate about democratizing art, offering it freely. Pre-pandemic, we had something called Adler Youth, a free program with high school students. We’re plugged into middle schools and high schools, we partner with drug and alcohol recovery centers, we were on Rikers Island—I can’t claim we’re part of that anymore, but we were on Rikers Island five days a week. We have a reentry program called Outside/In and are partnering with another called Ritual 4 Return. I want to keep building all that. It’s rooted in an Adlerian vision of an actor as an ever-evolving human being who is culturally and socially engaged. That hasn’t changed for me. I feel more urgency to open the doors and let people in to utilize the arts for the purpose of empowering humanity.

KAREMAN: I’m loving everything you just said, Tom. I’m thinking along the same lines, but you have been very proactive before the pandemic, in part because of that lefty sensibility Stella had and that she acted upon and talked about a lot. The tradition continues and I think that’s thrilling. When we wanted to celebrate the renovation and being back in the building this year, I chose to do a reading of Waiting for Lefty, which Meisner directed in 1935 on Broadway. We put out the call to some of our alumni and had a wonderful reading of a play that really lives today and can be related to by anyone who sees it and hears it.

I think 51 percent of the student population is on financial aid. The finances of it are a very difficult challenge. We have to run the joint, and I don’t want it to be on the back of these young and wonderful people. How can we alleviate that burden of going into debt to be an actor? It doesn’t make sense! So for our future, I feel very passionate about protecting this thing called the Meisner technique, helping it grow and helping it reach the world and helping people be better human beings. Because when you’re true to yourself, when you are your authentic self, you’re a better person, an honest and forthright person, and you have more compassion and empathy. We want to keep digging and not grow so much that everything becomes about the economics. We don’t need more students, our numbers are good, but I wish it were free. I wish that someone would come along and say, “Guess what? Nobody has to pay for the next 100 years.” That’s so naive! It’s a difficult task.

OPPENHEIM: You’re such a great conservatory. It’s so clear to me the benefits of the work that Sandy put together and what you do. I think continuing that work is vitally important.

KAREMAN: And back at you. I studied with Stella. It was life-changing.

OPPENHEIM: I was the person that called Sandy when Stella died. I didn’t speak to Sandy; I spoke to his partner, and he told me Sandy’s response. I have that indelible memory.

KAREMAN: That’s wonderful. One of my hopes for the future is more of this. You know what I mean? We are in our buildings doing our thing, but we should be coming together more. Because it’s so important.

OPPENHEIM: Yeah, that sounds great.

Isaac Butler (he/him) is the author of the forthcoming The Method: How the 20th Century Learned to Act and The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America. He cohosts Working, a podcast about the creative process, for Slate.com, and teaches in the College of the Performing Arts at the New School.