Who decides how actors should sound onstage? Why is “neutral” a goal in terms of speech? Who decides what is intelligible for audiences?

I spent the last eight years as a professor of voice and speech in a collegiate actor training program in New York City grappling with these questions. Despite coming out of graduate school with a whole toolbelt of other approaches to speech training, I was told I had to teach standard dialects because that was the curriculum, and I was discouraged at every turn from pursuing the answers to the questions I listed above. The power dynamic was clear: Do what you’re told.

When I continued to press my colleagues about why we were still teaching Standard Stage Dialect/Transatlantic, the refrains I heard over and over were, “You can’t throw the baby out with the bathwater,” and, “Well, students have never complained to me,” and, “They will need this to do Shakespeare, get cast, be successful in the industry, etc.”—all variations on “This is the way we’ve always done it.”

Grace Hopper, U.S. Navy rear admiral and renowned computer programmer, once famously said, “The most dangerous phrase in the English language is: We’ve always done it this way. It raises the question, ‘Are we doing this because we always have, or because it’s the right thing to do?’” In the case of teaching speech, as in all our curriculum, we must ask why we are teaching what we teach and how we teach it. Is it because it’s the best thing for our students to learn to thrive, or because it’s what we have inherited?

The Problem

Though standard dialects are still taught in acting programs across the U.S., you don’t hear many standard dialects, especially Standard Stage Dialect/Transatlantic, onstage in New York or in regional productions (let alone in films and TV shows). The speech needs of most productions I’ve seen and worked on have not included standard dialect; instead, each production was unique.

I grew up believing that the needs of the industry were what dictated our training. But I realized pretty quickly, as a professor, that much of performing arts education perpetuates the status quo rather than helping the field to evolve. It has been clear to me for a long time that using standard dialects as the foundation for speech training is problematic because it communicates that we value students who sound white, educated, and upper-middle-class. And it seems self-evident that shifting speech curricula to decentralize standard dialects could be one way to directly address a lack of inclusivity and equity in the theatre field, whose standards are still predominantly coded as white, cis-gendered, able-bodied, thin, educated, and privileged, with examples from everything from auditions and casting to costuming and season selection—and speech.

Today’s Gen Z students are exhibiting stronger boundaries and bullshit detectors than ever before. But even before my students felt empowered to express their concerns about learning Standard Stage Dialect/Transatlantic, I was questioning it. I questioned it when I was in undergrad but was not empowered to challenge it. As a professor, I had many incredible students from Puerto Rico, for example, who were nearly failing their voice and speech class because they were having to first translate their words into American English, then translate them again into the sounds of Standard Stage Dialect. How were we so obviously failing them? Beyond the ESL students, any students with regional dialects that were far from Standard Stage were unfairly having to work that much harder than students whose dialect was closer to the standard. The scales were tipped in favor of those closest to the standard.

When I brought up my concerns about the speech curriculum to my superiors, I was confused by the resistance; it seemed so obvious to me that this was a direct and tangible way to address inclusivity and equity in voice and speech. So I secretly chipped away at this in my teaching, gaining more courage each year to put more focus on projects that used idiolects, which address the speech patterns and language use of one individual at a time, thereby avoiding the dangerous terrain of lumping everyone from Boston, for example, into one generalized dialect and thereby reinforcing stereotypes. I was scared of retribution, but I knew in my gut that the departmental values needed to shift.

I wanted my students not only to be skilled in transforming their voices; I wanted them to become empathetic about how they, and other people, use their voices. As we studied idiolects and the actions of the vocal tract in a creative and exploratory way, students learned more about their own idiolects by holding them up in comparison to these other voices. Their starting place was not about having to assimilate to any one standard; they were instead able to learn about themselves through play and inquiry by studying one voice at a time. Treating all accent/dialect work from the point of view of idiolects brings a level of detail, specificity, and care to the work that gives actors the tools to take on any accent in the future.

What’s equally important is the time spent learning about the individuals whose voices we were studying. The biggest impact this approach has is to put the focusing on describing the sounds they perceive, so that actors gain both more knowledge and more autonomy to take on any accent they’re asked to attempt. Notably, Knight-Thompson Speechwork is based on this principle, teaching actors to explore all the sounds they can make instead of just one set of sounds. While standard dialects consist of a specific set of prescribed sounds that actors must acquire, they only equip students with one or two standard dialects; they do not arm them with the necessary skills to describe sounds, let alone any critical analysis or curiosity about the process—all essential tools for learning other accents.

This is especially true in undergrad, when students are often looking for the one “right” answer instead of engaging with the process. They often leave undergrad without a clear structure or process for breaking down an accent and taking it on in their practice.

Why hasn’t this obvious change been made? Despite college being a place where dissent and discourse are theoretically encouraged as essential components of critical engagement, power dynamics make it nearly impossible for students to feel comfortable enough to push back. Students cannot question what is being taught or how it’s being taught without fear of retribution because they are afraid of missing out on opportunities if they are seen as too disruptive.

Yet the pain point here is not just the power dynamic; it is the incapacity of professors to remain self-reflexive about whether or not what they teach is still relevant for students and is still adequately preparing them for the industry, which is in fact evolving, often at a faster rate than curricular and pedagogical reform.

When discussing the issues of resistance to innovation in collegiate actor training programs with my colleague from UC Santa Cruz, professor Amy Mihyang Ginther (she/they), they pointed out the hypocrisy in much actor training. “People who train actors to take greater risks,” they noted, “often shrink from risk themselves when it comes to doing what needs to be done to promote equity in our space.”

As educator Paulo Freire once wrote, “What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves.” Actor training should not press and shape students into mini-versions of the teacher or into the narrow box the teacher assumes is the one the actor needs to fit into; it should be culturally responsive and in line with the goals of the individual students.

When I was told over and over that my concerns about teaching standard dialects were “anecdotal,” I decided that doing the research myself was the only way to illustrate that the harm being done was a systemic problem. If I am not being heard as a faculty member, I thought, I will be heard as a researcher. I was frustrated by the lack of support for this innovation in my institution, as well as the pressure to legitimize the problem in the first place with hard data. I wondered how many other faculty members at other colleges were facing the same kind of pushback against change, especially when inequity and racism were at the heart of the problem. If I, as an educated white woman, wasn’t being heard, what about my peers of color? What about my students?

The Research

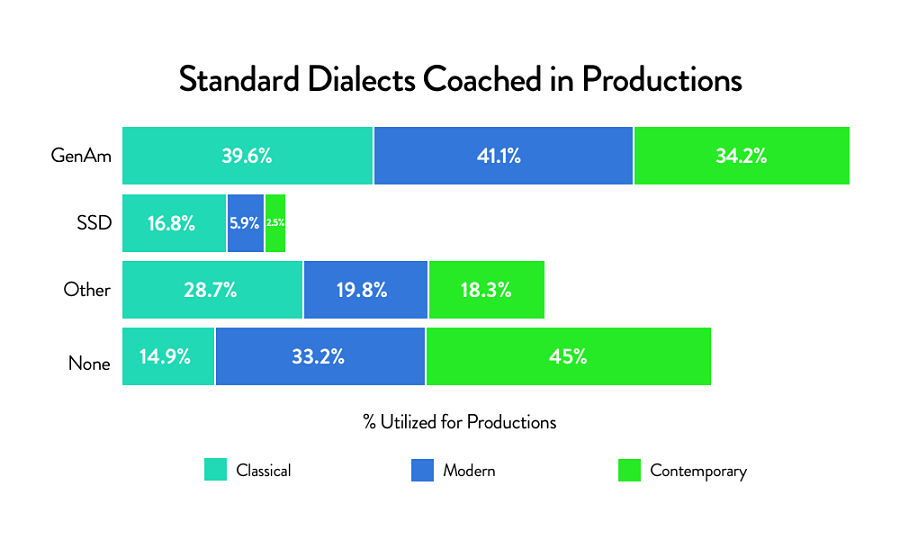

Rather than take the resistance personally, I pivoted and focused on the research. My colleague Joe Hetterly (he/him) and I had already surveyed the Voice and Speech Trainers Association (VASTA) in 2017 to learn what teachers and coaches were using in terms of standard dialects. The survey asked which standard dialects, if any, they coach for classical, modern, and contemporary. The results, initially published here, were as follows:

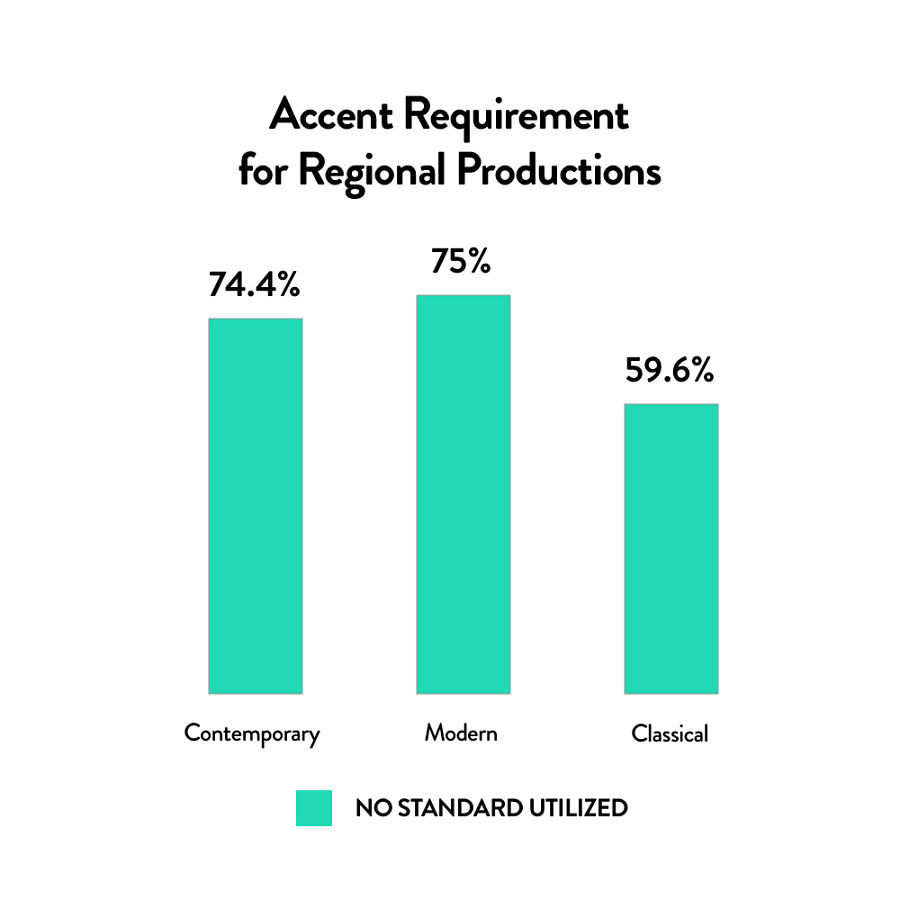

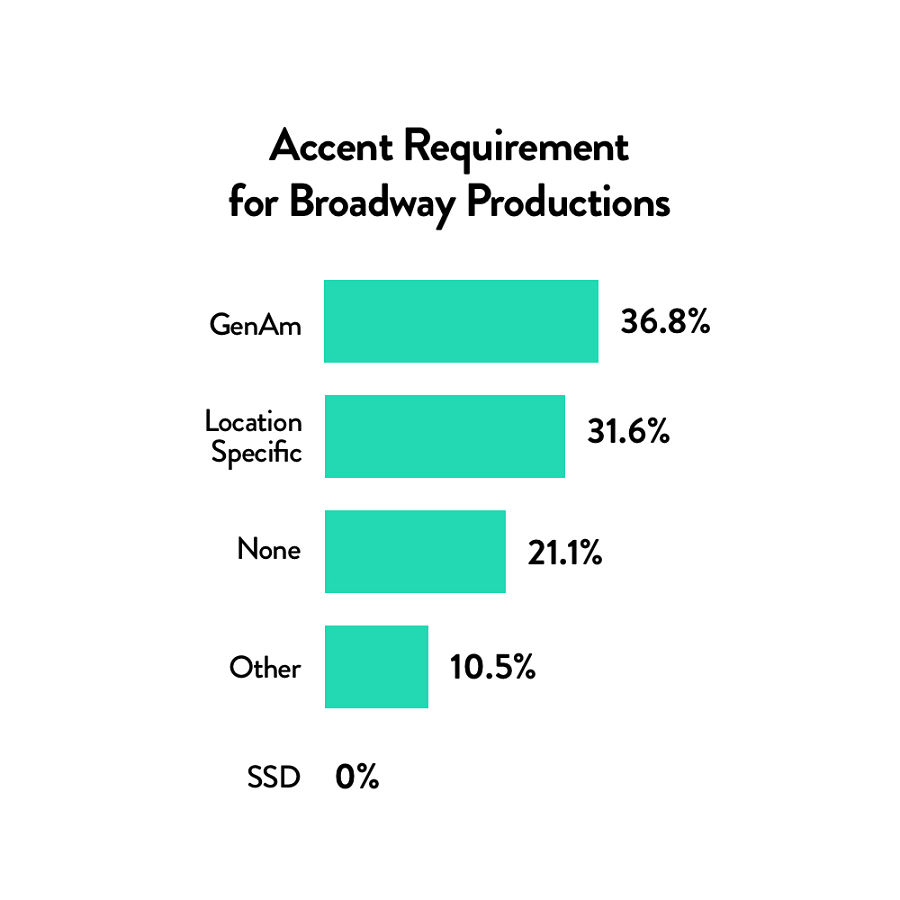

I brought the results and analysis to an Association for Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE) conference, where professors at other colleges were asking for more. They said they too were sick of teaching standard dialects and wanted to know more about what was next and how to convince their colleagues that this was an archaic practice. We expanded our team, bringing on statistician and scholar Ellen Kress (she/they), then took that charge and got to work surveying regional theatres across the U.S. and Broadway productions from the 2018-19 season to see what industry values were around standard dialects. We conducted expert interviews with artistic directors, casting directors, talent managers, and professional speech coaches.

The results, published here, are clear: Overwhelmingly, standard dialects are not being used in U.S. regional productions, and while 36.8 percent of Broadway productions used General American, none used Standard Stage Dialect. General American is still problematic because, as anti-racist theatre activist and facilitator Nicole Brewer (she/her) asserts, “It privileges the white narrative as superior by suppressing linguistic cultural markers in actors of color.”

So many professors are choosing to leave higher education now, as the pandemic pressed folks in ways that forced them to assess the institution and their role in it. It shone a very bright light on the systemic issues around EDI in ways that often were glossed over in the past: lack of funding and resources, overworked and underpaid professors, and inherent biases that are built into the curricula. With all that coming to light, it is not surprising that folks are choosing to leave higher ed or pivot to alternate career paths altogether. The conundrum with staying, as Ginther described so aptly, is that if professors choose to stay in their positions, trying to advocate for their students, they may then need to sacrifice, compromise, or not confront their superiors, because if they do “take a hard stand and say, ‘This is the hill I’m going to die on,’ then they might die on that hill. They might get fired or not renewed and then have no ability to help and advocate for their students.”

Ginther spoke what had been on my heart for my entire academic career: “The status quo is racist, and if I don’t do anything to resist it, then I am also racist because I am perpetuating it.” I felt complicit in staying at an institution that had so obviously resisted change and chose to further traumatize students, particularly students who were Black, Indigenous, and/or people of color, by teaching outdated material (an endless cycle of Streetcar and Waiting for Lefty scenes) and by using teaching methods that harm them (scarcity mindset, tokenizing, emotional manipulation, and teaching from a place of fear).

I left higher education at the height of the pandemic last summer and started a private coaching business so I could create a space where students wouldn’t have to make themselves smaller, reduce anything about themselves, or fit themselves into boxes that didn’t align with their career goals just because “that’s the way it’s always been done.” Students shouldn’t have to exclude parts of themselves in order to thrive. What has become abundantly clear to me is that we can’t wait for others to do the work; we must be the ones who advocate for more equitable, more holistic, and more inclusive environments both in training and in productions. This shift was happening before the pandemic, but now it is gaining major traction as programs are looking to hold themselves accountable for their former misdeeds and for upholding policies that alienated and discouraged students from taking up space.

Be Who You Needed

I have been asking myself, what am I teaching in place of what I inherited? I live by the quote “be who you needed”—and what I needed as a student and even as a professor was someone who wasn’t afraid to investigate their own inherent biases and preferences in what they taught and how they taught it. In reshaping my speech and dialect training, I’ve looked to the example of some theatre professionals who are working tirelessly to create better learning and rehearsal environments, including theatrical intimacy education, trauma-informed theatre practices, anti-racist theatre practices, non-Eurocentric acting training like Black Acting Methods, non-standardized speech training, and inclusive casting practices. I spoke with several practitioners of these practices and approaches to gain insight into the impact these pedagogies may have on the future of actor training. I hope reading about these three approaches will inspire you as much as they’ve inspired me.

Chelsea Pace (she/her) and Laura Rikard (she/her) are the co-founders of Theatrical Intimacy Education (TIE), a company that teaches about how intimacy choreography, consent-based practices, and boundary practices can help to shift the power dynamic in the classroom and rehearsal room. Establishing boundaries is a major component of TIE’s work, which includes, Pace says, “not only touch boundaries, but boundaries that are also social, emotional, cultural.” This way actors can communicate their boundaries in a transparent way that doesn’t require them to explain why they have boundaries. Pace explained that TIE also uses “consent establishment tools which help people understand the role of how power and pressure and the culture of the industry, both historically and currently, impact our rehearsal rooms because you can never be so kind or cool that power and the pressure to be ‘easy to work with’ won’t impact group dynamics.”

This is echoed in Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, in which he explains that an educational program cannot expect positive results when it “fails to respect the particular view of the world held by the people. Such a program constitutes cultural invasion, good intentions notwithstanding.” It doesn’t matter how well-intentioned decolonizing syllabi and seasons are; if BIPOC artists aren’t involved dialogically in the process, these efforts will perpetuate tokenization and deny their worldview.

And while most collegiate actor training programs have begun to acknowledge how racism, ableism, and classism have impacted their students, nearly all programs still have yet to address the assumptions around language in actor training that focus on the concepts of “neutral,” “natural,” or “universal,” especially as they relate to works of the Western canon. Ginther’s pedagogical approach explores Shakespeare, to take the most prominent example, from a perspective that acknowledges assumptions typically made about his work. She asks, “What does my practice look like if I’m starting from a place where he is not universal, where he is colonial, where he has been perpetuated from cultural materialism? He’s not just the best because he’s the most well known; he’s the most well known because certain people have continued to say he’s the best.”

Another example Ginther provides: Their dance colleagues frame ballet as a form of ethnic dance, an insight originally attributed to anthropologist Joann Kealiinohomoku’s work from the 1970s. We can no longer assume that Eurocentric performing arts practices are neutral. In fact, Friere reminds us that “the educator has the duty of not being neutral,” and in this case, they can do so by naming whiteness to frame the study of a ballet as a white, Eurocentric standard, without assuming that it has been normalized for everyone as the “best.”

Finally, once we acknowledge that Eurocentricity is not the default or goal for everyone, we can incorporate other methods into our curricula. For Black actors who have only ever been exposed to Eurocentric acting methods, they can center themselves in Black Acting Methods. Dr. Sharrell Luckett (she/her), founding director of the Black Acting Methods Studio, explains, “That’s one thing that’s so important—the Afrocentricity piece. Black actors, we tend to think about everybody else but ourselves. We tend to sacrifice ourselves in the classroom, in the rehearsal room, on the stage, for everyone else’s education.”

For teachers to have the willingness to remain flexible, especially after tenure, requires a great deal of self-understanding and self-compassion. It is okay that we don’t know everything. We do the best we can until we know better, and then, as Maya Angelou famously said, “When you know better, do better.” We know we need to examine what we teach and how we teach it so that we can be transparent with students and communicate that we are not making assumptions about what is universal, neutral, natural, or standard. This self-examination can make us feel incredibly vulnerable, but the very folks for whom we should not be afraid to be vulnerable with are the ones who see us as advisors, role models, and experts in the field: our students. We can be okay with not having it all figured out, without fear of being “cancelled.” Gen Z students value authenticity and transparency. As Ginther says, of the importance of modeling this vulnerability for our students, “When students tell us that we messed something up, they’re investing in us.” We owe it to them to invest in our own growth.

Melissa Tonning-Kollwitz (she/her) is an award-winning scholar and an international acting, voice, and accent coach. She is the founder of the PK Method, a holistic, voice-centric approach to acting which empowers actors to take ownership of their artistic practice through text work and vocal transformation.