Eric Keen-Louie can attribute much of his early interest in theatre to his parents. One of his earliest memories of theatre is being allowed to stay up late to watch the American Playhouse Into the Woods broadcast on PBS. His parents then drove him to the music store to buy the cast recording. Cast recordings then became a gateway into the field for him.

Keen-Louie, who recently took on the role of executive producer at California’s La Jolla Playhouse, said that his parents had had a deep love of theatre themselves, dating back years. Keen-Louie’s grandparents were immigrants from China, with his father’s side of his family owning a Chinese takeout restaurant and his mother’s side owning a laundromat. His parents would go on dates to the theatre, fostering a love of the field during the 1960s and ‘70s, thanks to affordably priced tickets. Keen-Louie said that his dad loves talking about seeing Baayork Lee in A Chorus Line. It just so happens that Keen-Louie was on a Broadway League panel last week with Lee (along with Linda Cho and Christine Toy Johnson). “It was one of the first times my dad was like, ‘Oh my God, you’ve made it, you’re on a panel with Connie from A Chorus Line!’” Keen-Louie joked.

Keen-Louie’s career has begun to have that full-circle feeling in other ways. Having worked at San Diego’s Old Globe for seven years as associate producer and later as associate director, and spending three years at the Public Theater as the assistant to the associate producer and director of special projects, in 2018 he joined San Diego’s La Jolla Playhouse as producing director, where he has overseen productions, including the world premieres of The Coast Starlight, Kiss My Aztec!, and Diana. He has degrees in dramatic literature from New York University and theatre management and producing from Columbia University and has assisted Broadway producer Margo Lion on Hairspray and Caroline, or Change.

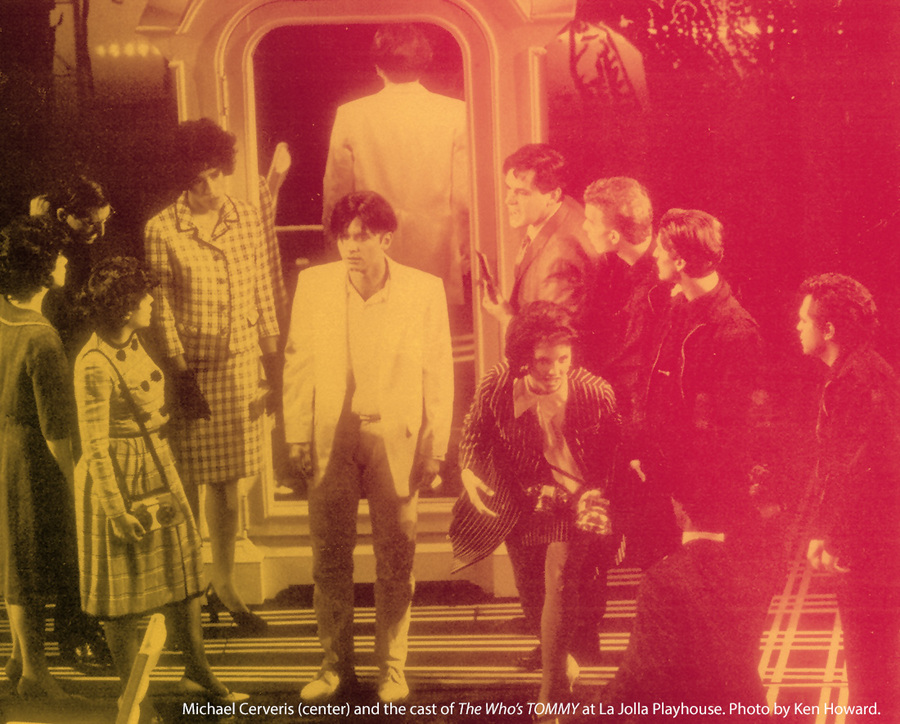

But as we sat talking on the phone last week, a day after his Broadway League panel, Keen-Louie’s eyes were drawn to a poster for The Who’s TOMMY, which premiered at the La Jolla Playhouse back in 1992. It’s a show that just so happened to be the first show Keen-Louie ever saw on Broadway. His parents, he said, couldn’t find a babysitter for him and his two brothers, so they brought the whole family. Seated in the last row of the balcony with binoculars, Keen-Louie said he sat there “enraptured by it.”

“The kinetic staging of it, the excitement, the energy that was coming from the stage,” Keen-Louie said. “I got hooked. I’ve been trying to figure out since seeing that, as I’ve gone through my career, how to get to La Jolla Playhouse—how to get to the place that premiered that thing that ignited my want of doing theatre.”

In 2019, shortly after Keen-Louie joined the Playhouse, the company had a TOMMY reunion concert, which reunited the original Broadway cast. It’s rare, Keen-Louie said, that theatremakers are able to have moments that remind them of the childlike wonder and excitement that got them interested in the field in the first place.

“But the moment that guitar strummed on that reunion concert,” Keen-Louie continued, “I was taken back to 10-year-old me. It was this insane out-of-body experience of reliving my entire life. Watching this concert, but remembering the purity of that moment of seeing that show at 10 years old and going, ‘This is what I want to do.’”

Career paths in this field can be difficult, Keen-Louie said, especially for theatremakers of color. But now, Keen-Louie looks to use his new position within the Playhouse’s leadership structure, moving to the newly created role of executive producer, to carve a path for the next generation of theatremakers.

“If I can create work that impacts the 10-year-old, third-generation, Chinese American kid who doesn’t think there’s a life for him in the theatre,” Keen-Louie said, “then it would’ve been worth it.” I spoke to him recently about his career path so far, and what lies ahead.

JERALD RAYMOND PIERCE: Your former title was producing director, and now you’re moving to executive producer. Can you tell me a little bit about the difference in role and responsibility between those two?

ERIC KEEN-LOUIE: The big change is that I’m really the one who’s overseeing the producing. I’m the lead producer of our subscription season. What that really entails is that I’m the one collaborating with every department. What does it take to create a show? I’m working with our in-house casting person, I’m working very closely with our production department, I’m working very closely with Gabe [Gabriel Greene], who is our director of artistic development—he’s really working on the dramaturgy work, and I’m working with the marketing team to make sure that we’re talking about the show in the way that the artists feel like we should be representing the show. I’m working with finance to make sure that the numbers are all adding up and we can do what the artists want to do. I am sort of the connector to the artists who are coming in to create the work.

So stepping into that role has been really exciting. But the other thing that my job has taken on is really to be the lead a point person, working in collaboration with Chris [Christopher Ashley], our artistic director and Debby [Buchholz], our managing director, to make sure that we are continually centering our EDI initiatives, our anti-racism commitment. The interesting thing about the job, and something I got excited about when we talked about creating it, is that because my job is interacting with every single department here and is the direct link to the artists, I’m making sure that the work that we’re doing institutionally gets infused into the process of those artists who are coming in and vice versa.

That symbiotic relationship to me is vital, especially in this moment of making sure that we are doing what we said we want to do, which is to make the Playhouse a safe space. It’s in our mission of safe space for unsafe and surprising work. We want the work to be challenging. We don’t want this process to be challenging, beyond what a normal artistic process should be of figuring out what that piece is and diving into it. We want people to be able to be their authentic true selves and also allow them to flourish in their creativity, not worrying that there are systems in place that are holding them back or making them feel unsafe.

As I listen to that, I can’t help but feel like that feels like a lot of—I don’t know if “pressure” is the right word—to put on your shoulders. It’s a lot of responsibility. So I’m curious, how are you looking at this and managing things for yourself to make sure keeping everybody else safe is also keeping you mentally healthy and safe?

I think that’s right. I mean, truth be told, I committed to this change of a job because of the work that the organization has been doing over the last couple years and in particular over the last 20 months. I have seen this organization dive into making deeper commitments to being an antiracist organization and an organization that is more equitable, inclusive, and accessible. If I hadn’t seen that, if I hadn’t seen literally every staff member ready to dive in—and not without our faults, we certainly stumble. This work is difficult. This work will never end. This work is something that you have to make sure is always a priority. But I’m seeing an organization making a genuine commitment from the top down, including the board, to make sure that we are meeting the moment, and not only meeting the moment, but making it better here.

If I didn’t see that happening, I wouldn’t have taken the job. I wouldn’t have said I want this new responsibility, because like you said, it would have been unsafe for me as a person of color. I’ve certainly been in many an organization where I’ve been the only senior leader of color, and the trauma I’ve experienced, truthfully, has almost driven me out of the field. I arrived here and felt, “Oh, this is a space that is ready to have me here in a leadership position.” And that’s been the shift for me in wanting to do this job—feeling like I’m supported and there’s buy-in, and I also have the staff helping me and working alongside me to make this change happen.

It means an immense amount to me that Chris and Debby saw the work I was doing and wanted to make space to have another collaborator with them to voice and continue to make sure that we’re prioritizing what we said publicly we would do. That’s not always common. I don’t know a lot of leaders who would make space for another person, let alone a person of color.

I love hearing all of that, because I remember OnStage Blog published an anonymous editorial from a Black director of diversity and inclusion at a theatre who talked about how she was brought in to do this work, but wasn’t feeling supported. So I love hearing that that commitment was there before they decided to expand this role.

I also think there’s this moment of danger that I feel for organizations that want to do this work, that the way they think to solve it is just to hire a person of color as the EDI person. What happens is that person gets marginalized into a box and all of the EDI work gets thrown on them. The thing about this job and why I was excited about it is that a large part of my job is producing the work. So I’m directly involved with producing the work that goes up on our stages, which is why we exist as an institution. And the other part of my job is making sure that I’m collaborating with the staff to prioritize and center antiracism, EDI, and accessibility work.

And the fact that my job, as the lead person doing both of them, means that the work that we’re doing is getting filtered through this lens and the work we’re doing institutionally is getting filtered through the art that we’re doing—that connection to me feels vital for an institution making actual change. Because if the EDI thing is getting pushed as, “This is the person on staff doing the EDI work here”—the fact that they’re intertwined to me shows we’re actually dedicated to doing this work.

As you look at the successes you’ve had at La Jolla, do you have any ideas or tips or examples of ways people at other theatres who may be in some of these positions you’re collaborating with can work with directors of EDI or with these leaders who are trying to do this antiracism work?

This EDI work has to hit the core of what you do and who you are. As we’ve gone through the last 20 months and how incredibly earthshaking We See You, White American Theater was, my biggest fear is that some of this work is happening because people are afraid of being called out on an Instagram post, that people don’t authentically want to make a change, that people are hiring people of color out of guilt, without any sense of understanding how to actually support them in the world they’re being hired for. In a sense, sort of doing things because they feel obligated to versus actually wanting to make change.

The biggest thing that I hope organizations have is intentionality, that the change you’re making is one you’re ready to and want to make, and that you are figuring out how to make sure that once you get that person there, that they’re actually being set up for success and you’ve actually thought through, uncovered, and put systems in place to make sure that happens. And that’s hard. That’s systemic, core-changing work. And I don’t know if every organization actually wants to do that work.

I ask myself that question on a daily basis, let me tell you.

Because it’s hard. This work is difficult. This work never ends. I’ve seen, in doing this work, people who just want to know that they’re doing a good job, that they’re getting a gold star. And the truth be told, all the work that we’re doing at the Playhouse, I’m feeling positive about. But we are stumbling along the way too. I think that’s natural. The thing that I’m seeing is, when we stumble, we’re acknowledging it, we’re figuring out who got harmed, and we’re working toward making sure that we talk to the people who were harmed and doing what we can to make sure they feel taken care of going forward. And that’s the biggest thing, right? My biggest fear is that people will start getting bored with this work, or it will become too hard and mistakes will be made and they just won’t want to engage. The engaging in the mistake-making is how you keep moving forward.

Of course, then you need to figure out how to not do harm after that. It is work that is sometimes one step forward, two steps back. But you’ve got to figure out how to make three steps after that. So it’s that commitment thing, it’s that core-hitting thing that’s important. And I am seeing that the [EDI] work that we’re doing here is making our [artistic] work better. I’m seeing artists breathe a little easier. We are doing the beautiful Kimber Lee play called to the yellow house with a predominantly BIPOC cast, and we have a BIPOC affinity group here, and we just had a lunch with them. It was so nice to be in a space with other BIPOC people in a predominantly white field. We are still a predominantly white institution, but the fact that our BIPOC staff here can break bread with these BIPOC artists who have come in to do this beautiful play, I think it’s amazing.

It’s the community-building aspect of it that I think sometimes we forget, because so much of this work can feel like I’m pushing a boulder up the hill. We can’t lose sight of the fact that this work is going to make the art better, but this work is also going to build a community in a different way in this field. That is exciting. That’s nurturing. That’s nourishing. And my hope is, and honestly the reason I do this work and I put up with a lot of the trauma I’ve experienced working in predominantly white institutions, is that I hope that for the next generation, they don’t find themselves as the only one in the room. I, for my entire career, have basically been the only one, and there are many who don’t want that to happen for this generation that’s coming up who are BIPOC wanting to work in this field.

Speaking of that next generation, as you look around the field, what are the biggest areas of improvement that you still see left for theatremakers as we push toward a more antiracist environment?

Theatres need to be better about learning about new talent. I think we have been at times caught in a cycle of hiring the same people over and over again. Which is not to say that I don’t want to take care of those brilliant artists who we work with all the time, who I love working with. But I also need to make sure that we are not just going back to the same well all the time. We need to continue to grow and expand the artists that we’re working with, and pairing some of those more established BIPOC artists with younger BIPOC artists so there’s that mentorship thing that happens that I so desperately craved growing up in this field that I feel like I never had. I love when I get to work with younger artists and artists who I’ve admired for years, because there’s learning that happens.

I think other thing is going back to, how do we make sure that we are creating a space for artists who are diverse who are coming in, to make sure they’re taken care of and they feel safe? We can research and try to recruit all we want, but if the artists who are working here as we’re trying to figure out diversifying and expanding our list are having a terrible time, the artists who we’re talking to and trying to bring to our theatre are not going to come. So you have to do both. You have to continue to build that steady and nurturing space for the artists you’re bringing in while also figuring out how to continue to grow the artists who you’re working with. If you’re not doing one or the other, they’re both going to collapse.

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor of American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org