When Anna Deavere Smith premiered her pathbreaking solo show Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 in the city of its title, it was May 1993, just little over a month after the so-called “second trial”—i.e., the federal civil rights trial of the four LAPD officers who participated in the vicious beating of Rodney King in early 1991, and who were infamously acquitted of misconduct in a Simi Valley trial in April 1992. That moral outrage not only led to some of the worst urban violence in U.S. history in the ensuing weeks; it also led then-President Bush to direct his Department of Justice to consider federal charges against the same officers. In what felt to many like a kind of do-over, on April 16, 1993, two of the officers were convicted, and two acquitted, of violating King’s civil rights.

Amid the vivid panorama of Twilight—assembled from interviews Smith conducted with a wide and diverse range of voices about and around the L.A. uprising and its various causes and effects, which she then reenacted entirely and brilliantly by, with only slight costume changes—one testimony popped out with uncanny immediacy. This was hardly surprising, as it was added to the show a mere 10 days before opening at the Mark Taper Forum: It was the inside story of a juror on the civil rights trial, who described in arresting detail how that jury broke through its various biases and hangups to reach its verdict. In what felt like a playlet-within-a-play, she narrated the twists and turns of their deliberations with vivid exasperation and bravura comic timing.

I had never seen theatre that felt so hot off the presses, so nakedly relevant to the moment I and my city were living through, and struggling to make sense of. As I wrote at the time, Smith’s unique outsider’s perspective on the class, race, and cultural conflicts that both led to and were exposed by the L.A. uprising, coupled with her fine-tuned editorial and curatorial sensibility, led to a “fugue of discrete experiences, seen from different angles, all gathered and reproduced with such clarity that we come out practically humming its buzz.”

Now that the play is having a strong new revival at New York City’s Signature Theatre (through Nov. 14), under the guidance of Smith and director Taibi Magar (she/her), but with a cast of five actors this time, I had two burning questions: How would Twilight hold up as a play, now that the events of 1992 are very much in the rearview mirror? And would it hold together without Smith’s extraordinary physical and emotional presence cohering its constituent parts, a theatrical feat about which Vinson Cunningham rhapsodized eloquently last year?

On the first point, duh: While the events in Los Angeles three decades ago are history, we are clearly still facing the grimly familiar problem of police brutality against Black Americans and a lack of accountability for same, despite an organized movement, and occasionally violent protests, against it. As Smith told me in a recent interview, she sees both racist state violence and the resistance to it, organized since 2013 under the name Black Lives Matter, on a timeline in which both 1992 and 2020, the summer of George Floyd, are major but not unique flashpoints.

“You know, there was no uproar when that video of Rodney King came out,” said Smith. “I remember no one thinking it could possibly be anything but a guilty verdict.” The shock of the officers’ full acquittal was one inciting incident of the April 1992 uprising, but she also pointed to a lesser known precipitating injustice, also addressed in Twilight: the 1991 shooting of Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl, by a South Central L.A. Korean convenience store owner, who was sentenced to a mere five years of probation.

While the violent response to the insult of these two verdicts—which conveyed the message that Black life and dignity were not worth more than property or state authority—may have appeared entirely reckless rather than organized, Smith noted, “One of the women who’s portrayed in the show says they started ‘No justice, no peace’ all the way back then. There was also a movement then, but the country didn’t realize that until they saw Los Angeles burn.”

Citing the stream of upsetting videos that began with the indelible camcorder capture of Rodney King’s beating, and have since grown to include the injuries and deaths of countless others, Smith said “the whole public and, in the case of George Floyd, the world have been educating themselves about—whether you want to call it police brutality, whether you want to say, is this another movement like the movement in the ’60s against imperialism and colonialism? I’m not sure; I’m not that type of a scholar. But, you know, white people are studying about race now, and the ’80s and the ’90s are a very important part of what ends up in colleges, and not only for Black students. So this is a different moment, and I think that what happened in L.A. is part of what has informed it.”

The pandemic shutdown may only have intensified this valence of the production’s resonance. Initially scheduled to begin rehearsals at the Signature in the spring of 2020, Twilight instead had time to gestate. Smith conducted some public conversations in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, while director Magar worked on the show’s archival video elements. “The projection designer, David Bengali, and I were continuing to work over the summer,” Magar recalled. “I would be on Zoom looking at images with him, and then we would click over to the news about George Floyd, and it was like, which footage is from 1992 and which is from now?”

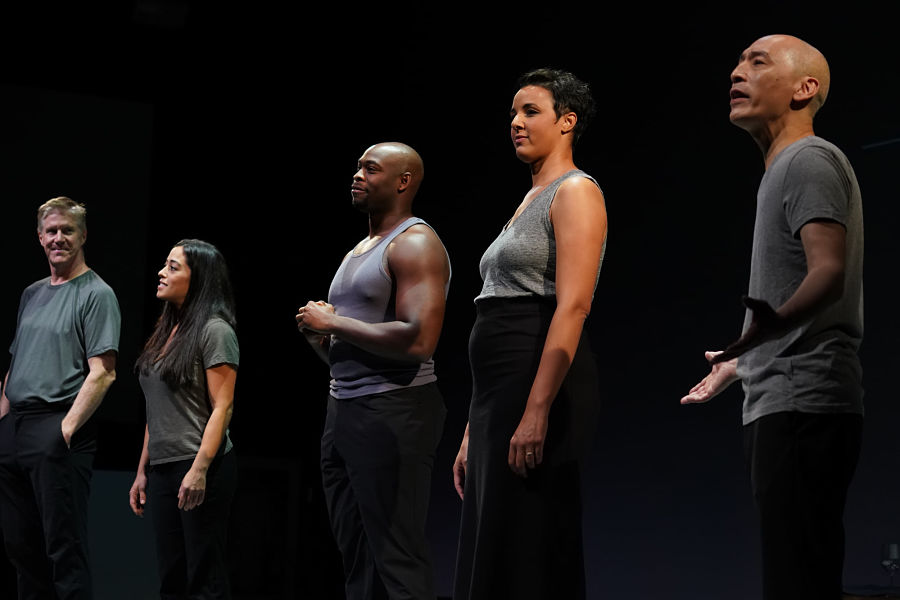

On the second point—whether this multi-actor approach, which has been authorized in educational settings and in at least one regional production I know of, would still do Smith’s unique vision justice—I shouldn’t have doubted the piece’s stage-worthiness. The monologues she brilliantly crafted 30 years ago stand up not only as timely reportage but as drama, and are embodied here by a versatile five-actor cast (Elena Hurst, Wesley T. Jones, Francis Jue, Karl Kenzler, and Tiffany Rachelle Stewart).

Getting into a room with them, in fact, prompted her and director Magar to consider revisions. Indeed, said Magar, “We shouldn’t be calling this the ‘revival’ whatsoever. It’s a living document.” Not only did Smith do some new interviews, including one in which one of the piece’s original dramaturgs, Hector Tobar, reflects on George Floyd’s murder and the COVID-19 pandemic. She also cut and pasted monologues into direct exchanges, as in a “dinner party” and other multivocal scenes.

She has even richly realized the full dramatic potential of that amazing juror’s monologue I mentioned earlier, which she calls the show’s “sort of 11 o’clock number. It’s a tour de force piece for one-person, and that’s the way I assumed it was going to be here too. But in one of the rehearsals, it dawned on me: My God, she’s acting out all the other people on the jury. How about if I have the whole cast involved in this?”

The result is no less of a showcase for actor Tiffany Rachelle Stewart, who leads us and her fellow actors through the raucous scene like a maestro. But it at last feels like the multi-character play this moment always cried out to be. As Magar and others have put it about Smith’s process, “I think she once said, if you keep anyone talking, eventually they’ll say something poetic.”

I asked Smith about this—about how she manages to make her characters feel not only like the protagonists of their own story, but dramatists of their narratives as well.

“Particularly when people are in turmoil, or in circumstances that are full of conflict and disarray, they really do find themselves in language in a magnificent way,” she told me. This language, she said, “has aesthetic value, has music, and very, very beautiful imagery. It doesn’t matter how educated they are. That’s what we have on display here.” In an analogy that rhymed with my own original assessment of the work, she concluded of her dramatic craft: “I really think of it more as playing music.”

The harmony of that music may only have grown more dissonant in the decades since the Rodney King verdict convulsed Los Angeles and the world. But from Fires in the Mirror to Let Me Down Easy to Notes From the Field, Smith’s work has always contained multitudes, in all their variety and complexity.

“As Johnnie Cochran told me when I interviewed him for Twilight, ‘There are three sides to every story: yours, mine, and the truth.’ I just don’t believe that any one of us holds the truth of this country. But it’s a sad fact of our tribalism right now that people think the truth is only inside their tribe. It’s just not.”

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org