This is one of three memorial tributes to Jim O’Quinn, the founding editor-in-chief of American Theatre magazine, who died on Oct. 11 at the age of 74. The other two are here and here.

Among the many things I loved about the ebullient, astute, eagle-eyed Jim O’Quinn was this: He knew that theatre existed, and in many cases thrived, far from New York Cit, or and even the Northeast corridor.

Yes, there is obvious synergy among New York and places like Seattle and San Francisco (the cities and theatre hubs where I’ve practiced cultural journalism), as well as Chicago and Houston, Milwaukee and Portland, Los Angeles and New Orleans; plays and assorted artists zigzag back and forth between coasts, and around the Midwest, the South, and wide swatches of “flyover” country. And to be sure, the imprimatur of a Broadway or Off-Broadway box office hit, a New York Times rave and/or a Tony or Pulitzer, still makes it all but certain that a play will be performed across the country eventually.

But as editor of American Theatre magazine for three decades, Jim understood that his mission—also the mission of Theatre Communications Group, which publishes the magazine—was to see beyond the obvious. He and they knew that as important as New York City is to the creation, exposure, and status of theatrical works and artists, there have rich and important things happening on stages all over this big, scratchy patchwork quilt of a nation for a long, long while. Those who understood that and, like Jim, were in a position to call attention to and champion a national theatre scene, helped make it possible for millions of theatregoers and waves of artists to be part of it.

Jim of course cultivated and mentored a crew of terrific New York writers to cover what was percolating in Manhattan and Brooklyn, what theatres and doers were up to, which all of us readers should know about. But he also made it possible for writers like me and so many others to alert him to playwrights and companies who deserved national attention despite their lack of proximity to a major media center or a phalanx of commercial producers. Just as Joe Papp forged a different kind of non-commercial theatrical model at the Public Theater, folks in many regions of the U.S. were establishing a countrywide network of nonprofit theatre scenes—ones that, at their best, reflect the multiplicity and diversity of life and creative expression that remains one of the best attributes of the American experiment (even as it lives under threat).

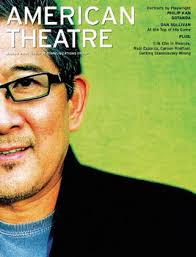

In my own case, Jim was always open to hearing about what was exciting me as a critic in San Francisco (for the San Francisco Bay Guardian) and Seattle (for the Seattle Times). Well before they made a New York splash, I was able to pique Jim’s interest in the Asian American theatre’s flowering, in works by West Coast writers like David Henry Hwang and Philip Kan Gotanda. In Stephen Wadsworth’s refreshed, relevant, and newly translated renditions of plays by Marivaux. In Yussef El Guindi’s sharply ruminative dramas about Middle Eastern Americans. In women directors in the 1990s at last breaking the glass ceiling to become artistic honchos of major regional companies, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Bill T. Jones revisiting and interrogating a troubling touchstone of 19th-century American drama, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

In my own case, Jim was always open to hearing about what was exciting me as a critic in San Francisco (for the San Francisco Bay Guardian) and Seattle (for the Seattle Times). Well before they made a New York splash, I was able to pique Jim’s interest in the Asian American theatre’s flowering, in works by West Coast writers like David Henry Hwang and Philip Kan Gotanda. In Stephen Wadsworth’s refreshed, relevant, and newly translated renditions of plays by Marivaux. In Yussef El Guindi’s sharply ruminative dramas about Middle Eastern Americans. In women directors in the 1990s at last breaking the glass ceiling to become artistic honchos of major regional companies, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Bill T. Jones revisiting and interrogating a troubling touchstone of 19th-century American drama, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

I can’t think of another editor of a national periodical who would have given me such a wide berth to explore such things more than 20 years ago, and who did the same for writers based in other cities thousands of miles from Times Square. This was of course not just Jim’s credo, but also that of Terry Nemeth, Betty Osborn, and James Leverett (publisher of many important plays in the magazine, and in TCG anthologies), and of course Lindy Zesch and Peter Zeisler, who for decades ran TCG and hatched the programs and services that continue to link and benefit disparate artists and theatres.

They fervently believed in the concept of a unique, and uniquely diverse American theatre: constantly evolving, and constantly in need of support and encouragement and exposure, as well as critique. Despite all of its challenges, past and present, such a thing still persists and matters today. And Jim O’Quinn should be remembered as one of the dynamic cultural patriots who made it happen.

Seattle-based critic Misha Berson (she/her) is a frequent contributor to this magazine.