Three new documentary films, each exploring a different period in Broadway history, couldn’t be timelier. They serve as gentle prods to those wary of entering a theatre, as well as a resounding “welcome back” message for those audiences eager to return, breathing a collective sigh of relief at the very prospect.

Celebration aside, two of the films—On Broadway (in select theatres) and Broadway: Beyond the Golden Age (on PBS)—provide refresher courses for those conversant in theatre lore, while simultaneously making fine introductions for non-aficionados who are nonetheless big fans. They’re ready-made for enthusiasts, in other words. The third film, The Show Must Go On (still awaiting release) is lower-keyed in tone and told from the insider’s perspective, even as its themes have broader application. Premiering in early August in Broadway’s Majestic Theatre as a fund-raiser for the Actors Fund, it considers two mega-productions (Cats and Phantom) that prevailed at the height of the COVID epidemic—not on Broadway or in the West End, but in South Korea. The doc functions as an object lesson, demonstrating how the show indeed can go on if appropriate precautions are in place.

Oren Jacoby’s On Broadway is surely the most “scholarly” of the lot, offering an informative if highly telescoped thumbnail sketch of Broadway’s ongoing evolution and reinvention over the last 50 years, from the growing role of nonprofit theatres on Broadway to the clamor for diversity onstage to the changing landscape (literally) of Times Square. It also casts its lens on the many contradictions that define Broadway. Director George Wolfe cites the most obvious, dubbing theatre both a temple and a commercial endeavor. “At the end of the day we have to pay our rent,” he says.

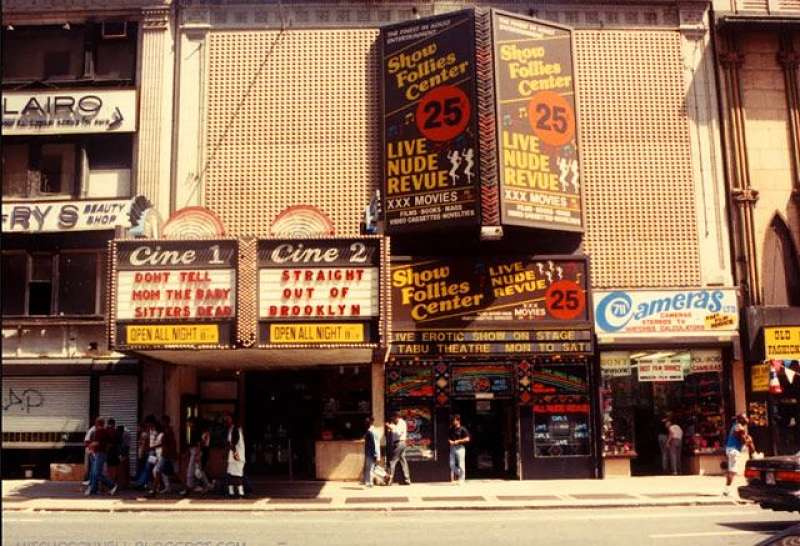

Throughout, a starry cast—Helen Mirren, August Wilson, Hal Prince, James Corden, Alec Baldwin, John Lithgow, Tommy Tune, Hugh Jackman, Ian McKellen—provides recollection and commentary. Mirren says she loves the current garish glitz of Times Square, even as she misses the gritty, abandoned Broadway of yesterday, awash in porn theatres, drug dealers, hookers, and crime. It was thanks in large measure to that neighborhood’s squalor in the late 1960s and early ’70s—Lithgow calls it a “rat hole”—that Broadway was virtually moribund. Times Square and its environs were off-putting to audiences, and it fare was viewed as dated, stale, and irrelevant.

Change began incrementally. In a series of rapid-fire snippets, we learn that Stephen Sondheim’s Company marked a watershed moment in its new musical style and timely subject matter. Shortly thereafter theatre landlords, starving for fresh properties, got into the act in a new way. The Shubert Organization’s head honchos, Bernie Jacobs and Gerald Schoenfeld, showcased the work of Bob Fosse (Pippin) and Michael Bennett (A Chorus Line), while Jimmy Nederlander (of the Nederlander Organization) brought Annie to Broadway sight unseen (Mike Nichols had given it a thumbs-up, and an uncredited touch-up, after he had seen it at Goodspeed Opera in Connecticut).

Change began incrementally. In a series of rapid-fire snippets, we learn that Stephen Sondheim’s Company marked a watershed moment in its new musical style and timely subject matter. Shortly thereafter theatre landlords, starving for fresh properties, got into the act in a new way. The Shubert Organization’s head honchos, Bernie Jacobs and Gerald Schoenfeld, showcased the work of Bob Fosse (Pippin) and Michael Bennett (A Chorus Line), while Jimmy Nederlander (of the Nederlander Organization) brought Annie to Broadway sight unseen (Mike Nichols had given it a thumbs-up, and an uncredited touch-up, after he had seen it at Goodspeed Opera in Connecticut).

It’s here, in the midst of the free-wheeling ’70s, that nonprofit theatre played its milestone role in shaping Broadway’s trajectory. There was the Public Theater’s role in the development of A Chorus Line, which ultimately broke all records, running 16 years on Broadway. A few years later, the Manhattan Theatre Club had a hit with Ain’t Misbehavin’; a few decades later, Rent shot its way onto Broadway and the world from its origin at New York Theatre Workshop.

Works developed in the nation’s regional nonprofits also helped diversify the work on Broadway, from the works of August Wilson to Angels in America. The film also makes the case that MTC’s production of The Nap, a Richard Bean comedy about a trans hit woman played by trans actor Alexandra Billings, broke ground for LGBTQ representation on Broadway, though this section feels both incomplete and tacked on.

A seismic turning point in Broadway’s renaissance was, though we Americans may hate to admit it, the British invasion that began with the epic Nicholas Nickleby and culminated in Cats, Les Miz, and Phantom. Not long after that, Times Square experienced a real estate boom. The film considers, in a little more depth than it gives other topics, the controversy surrounding the destruction of three beloved Broadway theatres to make way for the towering Marriot Hotel, and later the arrival—some would say intrusion—of Disney, an occurrence, like so much else on Broadway, overflowing in paradox. Yes, in many ways it fulfilled its detractors’ worst fears, turning a number of Broadway theatres over to glorified kiddie fare. On the other hand, it also made possible Julie Taymor’s visionary The Lion King.

PBS’s Broadway: Beyond the Golden Age covers much of the same territory, though it’s more clearly designed for the star-struck, without the benefit of cultural context. Its gushing is forgivable, though, because it’s so heartfelt. Its creator/director Rick McKay, a theatre worshipper if ever there was one, died before the film was completed. (Four of his producers finished the job.) The film is a sequel to McKay’s 2003 equally adoring theatre documentary Broadway: The Golden Age, and like its predecessor, it’s a free-flowing oral history with no shortage of folkloric (in some instances legendary) recollections. It spans 20-plus years, from the late ’50s to the mid ’80s, and includes the likes of Carol Burnett, Robert Redford, Liza Minnelli, and Ben Vereen, who recall the nightly joy of greeting the stage doorman and the ever-present stomach butterflies at curtain time, among other topics. As Elaine Stritch puts it, “The scariest word in the language is ‘places.’”

Minnelli recounts the wild ovation she received when she stepped in for Gwen Verdon in Chicago. Dick Van Dyke says that he landed his star-making turn in Bye Bye Birdie” by singing Ray Bolger’s calling card number, “Once in Love with Amy,” at his audition.

The film is gossipy and enjoyable—Mckay was a master at asking pitch-perfect leading questions—and adds a new tidbit here and there, even as it rehashes familiar material, not least the development of benchmark productions such as A Chorus Line, Ain’t Misbehavin,’ and Once Upon a Mattress, which launched the careers of star Burnett and composer Mary Rodgers.

Perhaps the most revealing Mattress story is Jane White’s. As an African American, she was keenly aware of her limited casting opportunities. “Broadway wasn’t ready to see Black people in anything but a certain color or a certain attitude, or a certain manner of speaking,” White says. She had auditioned for the role of the queen, and though director George Abbott was vehemently opposed, on the grounds that a Black woman would never be royalty in a medieval world, his assistant insisted she was perfect for the role, and brought her to a makeup artist to lighten her skin. She landed the role but felt conflicted, telling herself, “Now, Jane…isn’t that what actors are all about? Doesn’t Laurence Olivier put on a funny nose?”

The story that continues to render an emotional sucker-punch is Glenn Close’s recollection of her Broadway debut in Love for Love in 1974. At the last minute director Hal Prince tapped the young understudy to replace veteran actor Mary Ure, who suffered from drug abuse and mental health issues and was unable to learn her lines. Just before going on, Close received a note from Ure that said, “It’s a tradition in the British theatre for one leading lady to welcome the next. I welcome you. Be brave and strong.” Ure was able to transcend her own humiliation. It was pure class—an example of the theatre world at its best.

Transcending hasn’t been as easy when it comes to COVID-19, an airborne virus that for the last year and a half has shuttered theatres across the globe. One notable exception has been the theatre scene in South Korea, which was able, within certain parameters, to keep productions afloat. According to The Show Must Go On, a doc by Dori Bernstein and Sammi Cannold, not one South Korean audience member contracted the disease in the theatre, even as COVID rates in the country soared.

Shot at the height of the pandemic in South Korea, London, and the U.S., the film takes a behind-the-scenes look at the world tour of The Phantom of the Opera and the South Korean tour of Cats, both of which forged ahead against all odds, showing what can be done if the collective will is strong. Among other precautions theatres were outfitted with high-tech ventilation systems; props were sanitized backstage before and after each use; actors got COVID tests on a regular basis (after quarantining for two weeks prior to entering the country), and practiced social distancing in the theatre as much as possible.

Admittedly, rehearsals and performances were problematic. Mask-wearing was not viable. Some of the players said they were uncomfortable, but decided they “trusted” each other. Despite all safety measures, two actors contracted COVID, were hospitalized, and quarantined until cured, at which time they returned to the stage.

To this viewer, the actors’ determination to keep working looks more like desperation. It all feels like a high-risk undertaking, even in a country more committed than the U.S. is to safety (the country has logged a total of under 300,000 cases and around 2,400 deaths). Still, as Broadway theatres reopen, with vaccine passports required at the door and masks required inside, the film may give us a glimpse of our own uncertain future.

Simi Horwitz (she/her) is an award-winning journalist based in New York City who writes for Film Journal International and Forward, among other publications.