This is part of a season preview package.

It’s hard to deny that there have been changes to the theatre field over the last 18 months. As a fall of in-person programming is already upon us, many theatres have already made efforts to make positive: moving away from 10 out of 12 technical rehearsals, diversifying their staffs, hiring theatremakers of color to help lead them forward, or instituting new equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives. Many of these changes have come in response to demands from movements like We See You, White American Theater, the activism of local theatre communities, and industry trade groups.

But even at theatres that have made gestures in the direction of change—which isn’t all of them, by any stretch—questions linger.

“My issue is in the sincerity of it all,” said Chicago actor Sydney Charles (she/her). “These are the same theatres that, during the summer of George Floyd, put up the black boxes in their profile pics and then didn’t do anything. Or we still get excuses about, ‘Well, if we do that, it’ll affect the board.’”

As Charles sees it, some theatres are more concerned with the optics—not wanting to be called out on social media, for example, and how that might affect the company’s bottom line—than actually instituting lasting change. Just over a year after seeing theatres release statements committing to do better in response to WSYWAT’s social media call-outs, Charles is now seeing season announcements that feel more in tune with theatre circa 2018 than a vision for theatre in 2022.

“You’re already in an industry where, from the jump, you’re warned to not trust anyone,” said Charles. “It’s especially hard to trust people that don’t look like you. And then it is equally as hard to trust people who look like you, but are taking positions in these companies that have been harmful in the past but haven’t done any work to rectify the damage that’s been done in the community.”

I’ve heard similar thoughts and questions from artists around the country for months. In many interviews, often for articles on unrelated topics, I’ve included a simple question: Apart from a pandemic-necessitated lockdown and now a tentative reopening, have you actually seen change in the industry over the past year? Too often the answer has been a simple “no.” Other respondents acknowledged, as Charles did, that there have been some cosmetic changes. But many still have a deeply seated distrust in how lasting or impactful these changes actually are or will be.

But what is an artist to do with this distrust?

“Do you not work?” Charles wondered. She said she has turned down opportunities to audition for certain companies throughout her well-established Chicago career, and may continue to do so. In the meantime, she asked rhetorically, “Do you make your own space? But then it requires money, and then where do you get this money from? How much of yourself do you have to sacrifice?”

For many artists, these kinds of concerns can mean spending a career compartmentalizing: trying to balance working in a predominantly white male-led field while also trying to bring their entire selves to the work in those spaces. The hope of many is that the learnings from the pandemic have made that less of a necessity. But as revealed in “Emerging From the Cave,” an independent study conducted by Jesse Cameron Alick (he/him) and commissioned by the Sundance Institute, there’s deep skepticism among artists about whether institutions are actually committed to addressing these issues.

Alick interviewed more than 70 artists, many of whom echoed Charles’s sense that institutions seem to be acting out of fear rather than true aspiration to change. As Alick noted in a recent interview, that distrust isn’t a recent phenomenon—it is grounded in decades of experiences across the country, in all aspects of life, including the arts. Even Alick admitted that he doesn’t think his study is especially groundbreaking in terms of what is on artists’ minds; these thoughts have been brewing for years. What sets the study apart is the way it highlights just how unanimous these feelings are among artists of all levels and backgrounds.

What his study also found, though, was that individuals within institutions saw themselves as being “deeply engaged in reevaluating themselves.” So this substantial gap of trust exists in the gap between artists and the institutions they are once again working with in the coming months. What can be done to begin to bridge that gap?

“It really feels like the theatre industry, we’re on the edge of a cliff,” said Alick. “We can either fall in fear or fall in excitement, and it depends on how we communicate with each other.”

“I think one of the reasons that our field has felt so inequitable is because people on the inside have not acclimated to working with a lot of different people of different cultural backgrounds.”

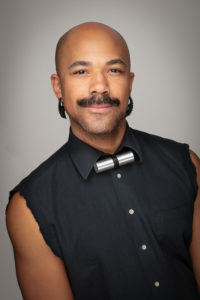

The difficult next step, Alick said, is to find ways to bring people together outside of the production process, in which the urgency of getting the next show up, then the next, can so quickly arise, and crowd out the space required for honest and fruitful conversations. Director and playwright Kareem Fahmy said he’s trying to have these tough, frank conversations during the hiring process to ensure that the theatres he will be working with are giving more than just lip service to calls for change.

“When I’m entering into conversations with any organization that could possibly support my work, either as a director or as a playwright,” Fahmy said, “what I want them to be able to articulate, or at least be able to respond to questions about, is what their value systems are when it comes to working with artists of color.”

Depending on the organization, Fahmy said, he may find himself in situations where he’s the first director or playwright of Middle Eastern descent they’ve worked with. So in effect what he’s asking the leaders of those companies what it means to them to work with someone with his background. There’s a certain responsibility he’s looking for—an acknowledgement and recognition that artists of color in these roles need a level of support that allows them to feel empowered to do their best work.

“I think one of the reasons that our field has felt so inequitable is because people on the inside have not acclimated to working with a lot of different people of different cultural backgrounds,” said Fahmy.

He gave the example of taking the time to talk through operational systems with artists coming in as guest directors. What’s the staffing setup? What are the roles and responsibilities of those around the building? For itinerant and freelance theatremakers, these answers can change with each institution. And the upshot of these questions is less about needing to know all of the inner workings of every institution, and more about knowing if, where, and how support will come, if and when it may be needed. Addressing these too easily overlooked questions up front can set artists up to work with the institution’s staff in the best way possible.

Fahmy acknowledged how difficult it can be to push against the scarcity mindset—the idea that he should just be grateful for getting the opportunity in the first place, and that he shouldn’t ask for what he needs to succeed or ask tough questions.

“That’s when people get taken advantage of,” Fahmy said. “That’s what led to all of the things that we’re now trying to fight against—all of the inequality, all of the inhumane working conditions, the long hours, etc. Starting with a core values-led conversation when I’m still in the process of trying to get a job at that theatre opens up a really important line of communication.” As he noted, “I think in every instance that I’ve had problems come up in a professional setting, it’s always because there hadn’t been enough communication at the outset or throughout.”

Starting these conversations during the hiring process can open the door to a more fully collaborative process. Fahmy doesn’t take these conversations for granted, and he acknowledged that some of the larger organizations around the country, especially those with long and at times complicated histories, aren’t particularly nimble when it comes to change. But he emphasized how important institutional leaders taking the time to have these conversations about their values systems can be.

The need for these conversations echoed words Ken-Matt Martin said as he took the reins of Victory Gardens earlier this year. “I’m making a renewed commitment to living by my values, which I think are aligned with the values of this theatre and the mission,” Martin told me last March. “To your question about how do you go about doing that: I had to sit and listen.”

So Martin went on an extensive listening tour, talking to Victory Gardens artists from throughout the theatre’s history. Other new artistic leaders have taken on similar listening tours. But that just makes me curious: How many current and/or long-standing artistic leaders have taken this pause as an opportunity to do the same themselves? How many have used the time away from the full-steam attempt to retake the stage to check in one on one with their artistic communities and have honest values conversations?

“Trust your intuition. Let that guide you and don’t let anyone take that power away from you and take it away from what you want.”

Fahmy noted a real-world example of how frank early conversations are helping his process. One 2022 project, for which he will be directing in an 800-seat theatre, is the largest directing contract he’s booked to date. While he’s confident that he’s up to the task, he also acknowledged that he’d never had to work in such a large space before. So in his initial conversations, he made sure to ask the artistic director if they would be available for mentorship or guidance, should Fahmy need it. Perhaps, he said, he’ll get there and everything will be easy. But coming to to an understanding with the artistic director that Fahmy wouldn’t be left to fend entirely for himself allowed him to feel supported in taking on the production.

“We have spent too long not talking about working together,” Fahmy said, “which is part of why people hire the same artists again and again and again—because they don’t want to put the time into figuring out how to build a new collaboration.”

Similarly, Los Angeles-based actor Natasha Ofili echoed the importance of feeling supported in her work during early conversations. She recalled preparing a speech for her first conversation with the director of one of her plays—a speech crafted to advocate for herself as a Deaf person, in hopes that the director wasn’t going to try to finesse away her vision. She was ready to sit down and have that potentially uncomfortable conversation, but it turns out that the director, Michael Arabian, expressed his support for her and her vision before she could even get into her prepared remarks.

Though that conversation went well, Ofili advised her fellow artists to have that inner fire and defense of their art ready for conversations with leaders in the field.

“Trust your intuition,” Ofili advised. “Let that guide you, and don’t let anyone take that power away from you and take it away from what you want. It’s a conversation, saying, ‘Okay, these are my needs. These are my wishes. This is what I want.’ Sometimes it’s scary to do that because you don’t know how that’s going to play out.”

While many major conversations around change and progress in the field have centered around racial diversity, Ofili noted that accessibility to Deaf and disabled artists and patrons remains the area where the field has the most room for improvement. There have been some glimmers of hope, especially on the audience accessibility side of things as theatres branched into digital presentations. But movement on that front has still been far from enough.

“It’s been 18 months and we have been seeing a lot of statements, but we haven’t really seen any action, or at least not much,” said Ofili. “So coming back into theatre in person, being back onstage and working together, I really do hope that they are following through with their word and keeping themselves accountable for that change.”

Moving forward, Ofili appealed to theatre leaders to think back to when they themselves were artists trying to make it in this industry, and then to enter into conversations with today’s working artists with more mindfulness and patience, taking the time to truly listen to both artist’s concerns and their visions.

Fahmy acknowledged the temptation of leaders to skip these tough conversations and work repeatedly with the same artists. But there’s a balance that has to be struck, he feels, between fostering long-term working relationships and building the trust of new collaborators.

Fahmy is also the creator of the Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) Director Database, created to help busy artistic directors and staffs connect with more diverse directors. The list had grown to around 400 names when we spoke in early September. It’s crucial, Fahmy noted, that the list be used as a collaborative tool, not simply as a way to fulfill a numerical commitment to BIPOC representation. There’s a big difference between actually committing to supporting an artist and their artistic growth, he said, and using their experience to meet an arbitrary quota.

There needs to be an optics change around diversification, Fahmy said. Theatres need to stop treating artists of color as “showpieces,” and to stop over-celebrating BIPOC hires or even all-BIPOC seasons, which can too quickly become about theatres performatively patting themselves on the back rather than supporting the work of those hires.

❦

As I ponder how to close the trust gap between artists and institutions, it feels like landing on a “well, just talk to each other” solution is just too simple. But as Alick reflected on what surprised him the most about his work on the survey, he said it was the universal desire among theatre workers for the industry to have a communal space for ideation—some location, whether physical, digital, or even spiritual, where honest and open conversations can be had about the problems in the field.

“It’s also the must ‘duh’ idea that you could possibly have after the last year and a half,” Alick said. “We clearly need to talk. We need to have a conversation with each other in many ways.”

The solution we don’t have yet: how to have these conversations in a way that is non-hierarchical, and not over-charged with power dynamics. There are many brilliant theatremakers in leadership positions, or just coming into them, with great ideas for how to change and improve the theatre field, and they deserve the time and space to see those visions through to fruition. But there are also so many artists out there who haven’t reached that positional mountaintop whose ideas simply go unheard.

It’s hard to say what form this kind of large-scale conversations might take. I like to think that American Theatre and its publisher, Theatre Communications Group, can at least begin to crack open those doors (TCG’s Fall-Winter Convening Season, “Crisis and Transformation,” kicks off in late October and includes a day-long forum on Nov. 13 to unpack the findings of Alick and the Sundance Institute’s study). But the scale and urgency at which these conversations need to happen can at times be overwhelming.

One thing is clear from these conversations, though: Artists must be ready to resist the gravitational pull of “returning to normal” over the coming months and years. As Alick put it, artists and theatremakers have a major task ahead of them as they return to in-person spaces.

“We have to be prepared to push back,” Alick said. “To hold our ground and not forget what the last year and a half taught us about our own boundaries, our own health, and how the American theatre should be treating us.”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor of American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that a conversation with Natasha Ofili happened with director Michael Arden when it actually happened between Ofili and director Michael Arabian.