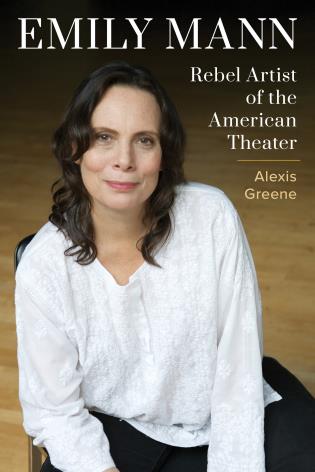

The following is an excerpt from Emily Mann: Rebel Artist of the American Theater, a new biography published by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, to be released Oct. 15; copyright 2021 by Alexis Greene. Through Oct. 31, American Theatre readers can pre-order a copy of the book at a deep discount by going to Rowman.com, opening an account, entering the book’s title on the on upper right of the screen, entering credit card info and using the code: EMANN35.

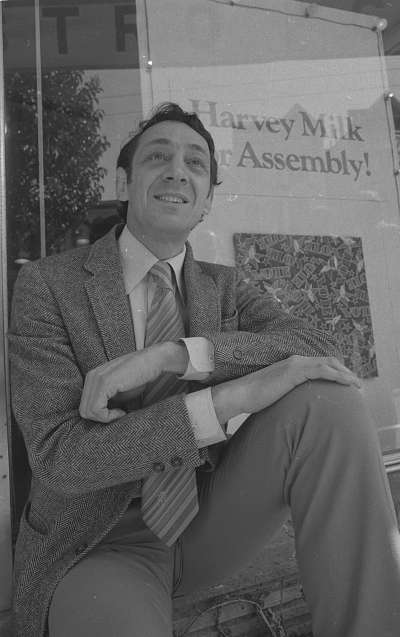

Nov. 27, 1978, was the Monday following Thanksgiving, and all over the country people were returning to work after the long weekend. In San Francisco that morning, a one-time cop and former member of the Board of Supervisors named Dan White went to City Hall with a loaded Smith and Wesson Model 36 .38 caliber revolver, and 10 additional bullets. He entered the building through a first-floor window to avoid the metal detector at the front entrance. White, who was 32, had recently resigned from the board, but he wanted to be reinstated and had learned that Mayor George Moscone was not going to reappoint him. White also knew that Supervisor Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay elected official, had lobbied against his reappointment. White walked to Moscone’s office, pleaded to be reinstated, and when Moscone denied the request, White shot him four times, twice in the head. He reloaded his gun, located Harvey Milk, and shot him five times, twice in the head. Both men died. Moscone was 49, Milk was 48.

White was arrested and six months later, in May 1979, he stood trial for first-degree murder. But the prosecuting attorney was weak, the defense attorney charismatic, and a psychiatrist testified convincingly that White’s high sugar intake had resulted in “diminished capacity”—the infamous “Twinkie defense.” Instead of premeditated murder, the jury found Dan White guilty of voluntary manslaughter, and when the verdict was announced, late on the afternoon of Monday, May 21, San Francisco’s enraged gay men and women took to the streets. In what became known as the White Night riots, they were met with tear gas and blows and arrests by equally furious police, retaliating for what they considered the desecration of San Francisco. The judge sentenced White to seven years and eight months in prison, the maximum sentence for voluntary manslaughter.

Three years later, in 1982, San Francisco’s Eureka Theatre commissioned Emily Mann to write a play about the assassinations, the roots of the violence, and the aftermath.

Mere hours after Moscone and Milk were murdered, Tony Taccone, the artistic director of the Eureka Theatre, joined thousands of people on a candlelight march for the slain men. He had particularly admired Harvey Milk. “If you were on the left,” said Taccone, talking with me one afternoon at the Public Theater in New York City, “you couldn’t help but love the guy. He was a bit of a showman, had that showman’s energy, but he understood how City Hall worked. Harvey represented a powerful bloc of people, people moving to San Francisco. To come out. Like a Mecca. And we at Eureka were in the heart of that.”

But three years had passed since Dan White shed blood at City Hall, and Taccone and his dramaturg, Oskar Eustis, both of whom aspired to forge a political identity for their theatre, had still not presented a play about the assassinations. In fact, they had mostly produced British plays. But they were eager to delve into American work, and with that goal in mind, in April 1982 the Eureka produced Still Life, which Taccone directed. “[Still Life],” he said, “was a very powerful experience for our audience, and for us.” A play about the murders of Moscone and Milk could be an even more potent experience. What followed, Taccone recalled, was “a kind of tumble event”; things moved quickly. Mann and Taccone sat in his house in Berkeley, “jammin’ on the idea” of her writing a play about the Dan White case. Taccone, Mann, and Eustis consumed Randy Shilts’s new book, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life & Times of Harvey Milk; Mann gravitated toward using the trial as a framework for the play; and the Eureka commissioned her. “We paid her probably 20 bucks,” said Taccone. “It wasn’t a lot of money.” In fact, he said, “Emily was ahead of us in her career. We had a good, strong local reputation, but we were pretty early in our work life.”

For Mann, the murders in San Francisco were another example of the American violence she had witnessed and experienced. In a 1983 interview with costume designer Michael Murphy in Seattle, when she was directing Franz Xaver Kroetz’s Through the Leaves at the Empty Space, Mann said, “There is a real connection between what the gay community goes through and the kind of oppression that women have gone through. And the kind of fears that we all walk around with…to be an obvious target, as women are late at night, or a lone gay man is in many areas of San Francisco. I understand that. I understand that terror and that rage.”

Mann felt she was at a crossroads. Her drive to direct had been unswerving in Minneapolis and had steered her to New York. “The career side,” she wrote in her diary in November 1981, has “been my life so completely.” And while she had no intention of giving up directing, that particular ambition felt, for the moment, less enticing than her marriage and the rewards of writing. At times she felt depressed: She was concerned about her health, for she was prone to headaches and stomachaches, which she blamed on “cigarettes, coffee, and liquor.” But at other times she was “elated, refreshed, and loving rediscovering my love for the art of writing.”

Also, Mann wanted a child and, she wrote her mother, so did her husband, Gerry Bamman. But as she confided to Sylvia Mann seven months later, in May 1982, “I feel I am not ready yet for children or childbirth and then I think: Well, ‘ready’—what does that mean? And then I think about how creative I am feeling again—writing, directing, being with Gerry…and I don’t know. Of course, I think, too, about how wonderful it would be to have a baby with Ger and the joy of bringing up a person together, but it seems as if it would also stop the flow of something magical that is happening right now.”

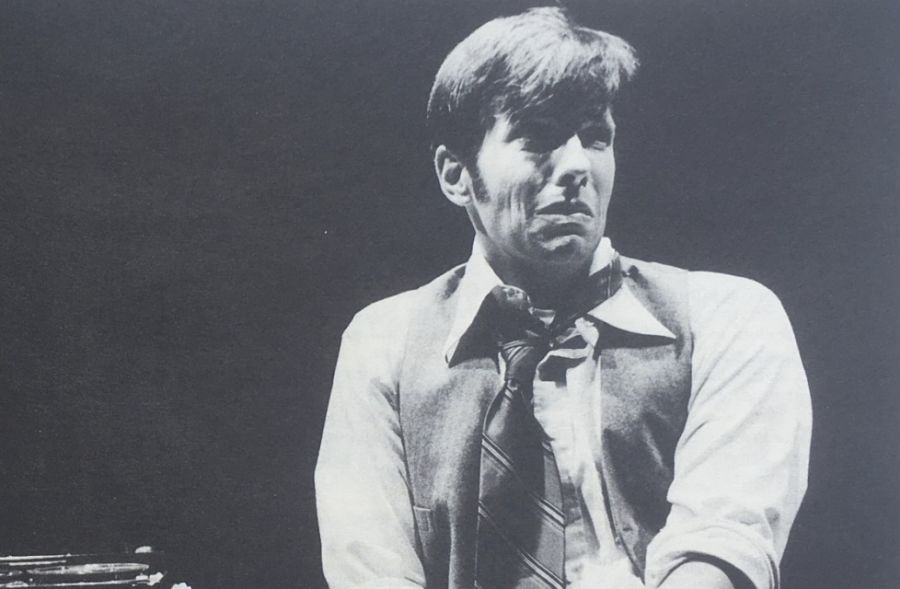

She did not forgo directing completely. In May and June of 1982 she staged Still Life in Los Angeles. In July and early August, at Bruce Siddons’ Oregon Contemporary Theater in Portland, she directed Christopher Hampton’s adaptation of A Doll House, on which she and Gerry made their own textual adjustments. Mary McDonnell played Nora, according to the critic Roger Downey, as a “lovable dimwit,” and Bamman was “explosive” as Nora’s husband, Torvald Helmer. In a bit of casting that delighted Portland’s movie buffs, Wallace Shawn and André Gregory played Nils Krogstad and Dr. Rank, respectively; their popular film, My Dinner with André, had been released the previous year. Gregory played Dr. Rank, Downey wrote, like “an almost campy old bachelor,” and Gregory, years later, recalled that he visualized Dr. Rank “as somebody in the closet who absolutely loves women, and women like to confide in him.” At one point, so Gregory remembered, Mann asked for a “more masculine” interpretation, and “I did Arnold Schwarzenegger, and she was delighted to go back to my original concept.” Gregory described Mann “creating an environment of fun and safety.”

But alongside directing assignments, what Mann and the Eureka were calling The Dan White Project absorbed her attention and her intensity. While in Portland, she requested as much material about the assassinations and the people involved as the Eureka’s small staff could supply. She and Oskar Eustis exchanged names of individuals to be interviewed, some by Eustis and others at the Eureka, some by Mann whenever she could return to San Francisco: politicos, reporters, and newscasters; police, lawyers, relatives and friends of Moscone and Milk; people who lived in San Francisco’s so-called working-class neighborhoods, and people in the gay neighborhood known as the Castro, where Milk had lived. “It was almost like we were doing the initial auditions, and she was doing the callbacks,” said Taccone.

Eustis sent a stack of newspaper clippings and the huge trial transcript to Mann in Portland. Of course, there were no “thumb drives” for storing files in 1982, not to mention personal computers or laptops, and Mann remembered lugging around a duffel bag filled with pounds of Xeroxed court testimony. She even dragged it with her to Thailand, where Gerry Bamman was filming Saigon: Year of the Cat, a low budget but well-cast Thames Television film about the collapse of South Vietnam and the final days of the Vietnam War. Directed by Stephen Frears from a script by David Hare, the movie starred Judith Dench and E. G. Marshall, and featured Wallace Shawn, Roger Rees, and Pichit Bulkul.

When an actor failed to make it to Thailand, Frears enlisted Mann to act the small part of an American left behind with the South Vietnamese after U.S. Embassy personnel flee the country. The last frame of the movie has Mann, alone, in silhouette.

“I don’t think I read through the [trial] transcript more than once,” Mann recollected about the beginnings of Execution of Justice. “I think I read through the transcript and I highlighted and underlined those things that popped out at me, that were funny, weird, brilliant, important…When I read those psychiatrists’ testimonies, I just was amazed…I also was very moved by Mary Ann White [Dan White’s wife],” whom White called immediately after the murders, asking her to meet him at a church. Mann’s first assignment to herself, as she phrased it, was to figure out, “How do you tell just the story through the transcript?”

One approach, explored in Mann’s early private notes, was to have “Trial onstage—audience is audience in courtroom w/ actors/characters in audience.” Her notes suggest that she contemplated putting “Mrs. Dan White front row – Reporters, etc.” and “during ‘trial breaks’ do ‘news coverage’.” The play would be written in “Hyper-real style—performance documentary—but we are distilling and making electric in two hours what was a year long building up to this event and the trial itself.”

One approach, explored in Mann’s early private notes, was to have “Trial on stage – audience is audience in courtroom w/ actors/characters in audience.” Her notes suggest that she contemplated putting “Mrs. Dan White front row – Reporters, etc.,” and “during ‘trial breaks’ do ‘news coverage.’” The play would be written in “Hyper-real style – performance documentary but we are distilling and making electric in two hours what was a year long building up to this event and the trial itself. And its repercussions.”

Among her jottings, “The big question: Why was justice not done? A man murdered/assassinated two public officials in cold blood and will be out next year. Why?” She experimented with possible titles: Getting Away With Murder. The Trial of Harvey Milk, or the Twinkie Defense. Even, perhaps in a lighthearted moment, Trial by Twinkie. As she delved more intensely into her subject, the notes became more specific, until at one point, possibly weary of over-thinking, she wrote, “I go to sleep dreaming it. It’s time to write it. I know what I’m writing now.”

Alexis Greene (she/her) is an author and arts journalist. www.alexisgreene.com