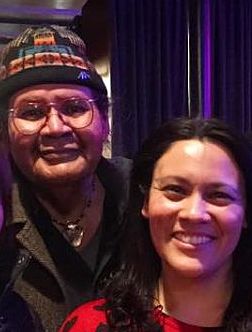

Playwright William S. Yellow Robe Jr., author of Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers, Wood Bones, and Better-n-Indins, among many other plays, died on July 19. He was 61.

Bill was the first Native person I had met for whom theatre was their life’s work. He was a consummate artist, and I believe he would have wanted to be remembered not for his quotes but for the full, complicated, and beautiful existence he and his writing spent a lifetime perfecting. I am just one person who was there in his audience, one witness to attest and argue for this Indian man’s humanity.

I was 19, attending the University of New Mexico when a flyer on the theatre department corkboard said, “Casting Native female.” As I was the only Native student in the theatre department, my playwriting professor, Digby Wolf, encouraged me to meet Bill and see what he had to say.

He was the biggest Indian I’d ever met and the first Assiniboine. Over six feet tall and heavyset, he had a sing-song quality to his booming voice. He told me about himself in what I didn’t know at the time was the trademark Bill Yellow Robe way, of reciting full histories of the theatre artists he had worked with and plays he had worked on that influenced his philosophies about theatre and life in general.

Bill left a position at the Institute of American Indian Arts and had come to Albuquerque to be an adjunct professor in the American Indian Studies department and to start a theatre company. Wakiknabe was the definition of grassroots. He brought together Native folks who’d never done theatre, would never do it again, and people like me who eventually were going to devote their lives to it, or to another way to better the status of American Indians. We were scrappy and new to the work, but Bill always treated us like the professionals he wanted us to become admonishing us to take the work seriously like him.

He ran rehearsal rooms like an old-school Stanislavsky devotee, not tolerating us coming to rehearsal late, without our lines memorized or not ready to work hard. His generation of Indians were used to lecturing us younger generation about the hard knocks they endured, whether it was beatings at boarding school, beatings of the body and spirit in reservation border towns, or the systemic white supremacy that never let Native people even think about participating in structures like theatre that made life beautiful for others.

If you knew Bill, you knew his community. He didn’t go a day without crediting people like John Kauffman, Curt Dempster, and talking about his favorite playwright, Eugene O’Neill. He imparted a love for the craft and art of theatre while embodying Indigenous values of relationship and community. If you asked him what success looked like, it wasn’t to have our work on the stages of predominantly white spaces; it would be a theatre in every Native nation. It would be Native artists valuing their cultural traditions over the rationed rewards of white systems created by white minds, Native artists taking care of each other, never believing in scarcity. It would be theatre his mother could see herself in, and lots and lots of spam at the concessions.

Wakiknabe produced brand new plays and classics. He played Vladimir, I played Pozzo. We performed for large audiences and we performed for audiences where there were more of us onstage than in the seats. Bill took us to New York to tour his play The Council. A couple of us in the ensemble bought tickets to see our first Broadway production with our cash stipends. When we found out the price, $80, at the ticket booth, we were all too intimidated not to hand over the money, while Bill stayed back at the hotel, not naïve about the profession that to us looked like a mirage in the distance. But he made sure we saw important stuff too: Spiderwoman Theater at La MaMa, and a visit to one of his homes, the Ensemble Studio Theatre.

Bill was not commoditize-able. Never would he claim at the top of any of his shows that it’s okay for white people to laugh, nor would he address concerns about their comfort level while his characters spoke truth. But he would say: Yes, you may laugh, if you take on this burden, this history, and this charge to dismantle your role in the oppression of my people. He never let an audience off the hook, non-Native or Native. He confronted the kind of racism he lived with growing up in Montana, and never backed down from internalized anti-Black and anti-Indian sentiments in our own communities.

He struck fear in the hearts of Pretendians and sellouts; he was large and brown and was often the only one a young Native theatre artist could turn to who understood the peculiar heartache the American theatre could inflict on a Native soul. He never let anything be left unsaid, and when he couldn’t, he’d write the best of the best Facebook shade—ayyyy! (Sorry for those of you who won’t get that last bit, but Bill would have loved it.)

When I started my own company, New Native Theatre, we would go on to produce four of his plays. We even toured his one-act Sneaky to Standing Rock in 2016 for a crowd of water protectors. That was the best show I’d ever had the honor to be part of; I can still hear the roar of laughter and the incredibly silent moments when his characters asked to be heard.

He alchemized the pain of genocide, racism, and an American theatre too fearful to widely produce his work into transcendent moments of comedy and truth. Bill’s plays were for Native people, period. But the honesty, the craft, and artistry he channeled into his plays from his life’s broken hearts, hard-fought wins, and unexpected deep joy—that was for everyone.

Rhiana Yazzie (she/her) is a Navajo playwright, filmmaker, director, performer, and producer.