“If nothing else, it puts the industry on notice.”

So concluded my recent interview with Tatiana Siegel, a reporter for The Hollywood Reporter who I knew briefly two decades ago when I worked at Back Stage West (the two trades once had the same owner). The “it” she’s referring to is the indispensable beat she’s carved out as an investigative reporter about the misbehavior of Hollywood executives, and it has indeed put the industry on notice: A series of 2019 stories about sexual misconduct among high-level Hollywood producers cost Warner Bros. CEO Kevin Tsujihara and other executives their jobs.

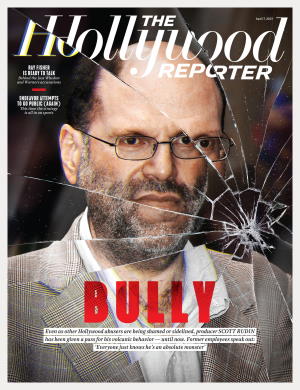

While she has mainly covered film and television, Siegel also shook the theatre industry with a blockbuster April 7 article that finally, belatedly, broke the story of theatre and film producer Scott Rudin’s legendary bullying and alleged abuse of his employees and colleagues in excruciating detail. As she wrote in a blistering follow-up report last month, Rudin anecdotes had long been “passed around Hollywood parties like mushroom canapés, occasionally surfacing in a profile that focused on his genius and with enfant terrible framing.” To my shame, I can vouch for them also being a sort of gossipy currency in theatre circles as well, since Rudin operated chiefly out of New York and, by most accounts, had his heart in his prolific theatre producing more than his film and TV dealmaking.

While she has mainly covered film and television, Siegel also shook the theatre industry with a blockbuster April 7 article that finally, belatedly, broke the story of theatre and film producer Scott Rudin’s legendary bullying and alleged abuse of his employees and colleagues in excruciating detail. As she wrote in a blistering follow-up report last month, Rudin anecdotes had long been “passed around Hollywood parties like mushroom canapés, occasionally surfacing in a profile that focused on his genius and with enfant terrible framing.” To my shame, I can vouch for them also being a sort of gossipy currency in theatre circles as well, since Rudin operated chiefly out of New York and, by most accounts, had his heart in his prolific theatre producing more than his film and TV dealmaking.

While previous articles about Rudin reflected the industry’s overly obsequious attitude toward the powerful by treating his tastemaking savvy and cunning as the central story, relegating rumors of his rage and control-freak behavior to eyebrow-raising side dishes, Siegel’s reporting at last reordered that priority. She opened her story with a harrowing scene from 2012, in which an infuriated Rudin allegedly slammed a computer monitor on an assistant’s hand, sending that employee to the emergency room bloodied and traumatized. And while she included quotes about Rudin’s significance as a producer and his strategic deployments of charm and intellect, she cast those in sharp relief with tales of tantrums and abuse that put him so far beyond the pale that in the wake of the story’s publication, and follow-ups from New York magazine and The New York Times, Rudin felt compelled to issue a pro forma apology and withdraw his name, if not all of his influence and financial stakes, from most of the projects he was working on at the time, including such Broadway productions as To Kill a Mockingbird, The Music Man, and West Side Story.

Rudin’s future in the business remains uncertain, not least while productions he originated continue to take up real estate on Broadway; the hope of many in the field, myself included, is that equally or more savvy producers who don’t have a reputation for abuse will fill the void left by his withdrawal. Also uncertain: the future of this kind of sustained attention to the abuse and exploitation the entertainment business has for too long enabled, ignored, perpetuated, even romanticized. This is where the role of those who report on the business is especially crucial, especially in a post-#MeToo world where what passes for accountability for workplace crimes more often comes via the press than the courts.

So I was curious to talk to Siegel, one of the leading journalists on the frontlines of a rapidly changing field, about the process by which she landed this huge, industry-shaking story, what she thinks the impact of this kind of coverage will be going forward, and how journalists can do this essential work responsibly and fairly. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: First, congrats and kudos on these pieces. When I was at Back Stage West, 20 years ago and more, I know that THR did a fair amount of labor reporting, but I don’t remember investigative pieces about workplace harassment and abuse being so frequent. Is it your perception also that this is a relatively new emphasis—that the entertainment trade papers feel like, “This is an area where people are calling the industry to account for its problems, and we’re going to report it”?

TATIANA SIEGEL: I think it’s because we moved from a daily back in the day to a weekly. That gave us more luxury to stop and think about stories in a larger, more thorough way. It wasn’t just like, this deal closed, that deal closed—you could actually delve into abuses in the industry.

My other question is about the nature of trade magazines, which have historically relied to a large extent on access and advertising from film studios. Has this investigative beat, which regularly calls major companies and players to account and can cost people lucrative jobs and projects, always been welcome at the magazine?

Absolutely. I mean, it is surprising to some, but you know, when I did the reporting on Kevin Tsujihara, I’m sure at the time Warner Bros. was—and still is—a major advertiser. But I’ve never even had a conversation about it. There’s never been any kind of pressure put on me in any way in my years at The Hollywood Reporter.

Obviously, you get pushback and legal pressure from the people you’re covering, I imagine, but you’re saying the call is not coming from within the house? That’s impressive. I would not have thought that was the case at a trade magazine, but I will take your word for it.

Yeah, never. When Jay Penske took over as owner in November, on his first day the magazine had to sign off on a very delicate and contentious story of mine regarding Charlotte Kirk, the actress allegedly being exploited by some of the most powerful people in Hollywood.

There’s a lot of abuse and exploitation in entertainment; you could fill several issues with stories about it. And it’s clearly not the only thing you write about. So how do you decide when to report on this topic, and when to, say, interview a director whose work you admire?

I just like to write the kinds of stories I would want to read. So it’s not always a steady diet of horribleness. It always has to pass my internal bar of intrigue.

So let’s get into the Rudin material. Obviously his reputation for bullying was legendary, and too many of us in the business, to our shame, knew about it without thinking we either could or should report it. What was the breakthrough or turning point that made you say, okay, now it’s time to report this story?

There seemed to be a growing trend toward zero tolerance for bullying and we were working on a story related to that. I had pretty much completed my story, and it was almost an afterthought, like, “Well, we all know Scott Rudin has been a bully forever—surely he can’t still be bullying.” I just assumed he had stopped in 2017, when everyone started taking a closer look at their own behavior, post-Harvey Weinstein, and realized that it was not going to be tolerated anymore. So I started to make a couple of calls, and it was like Amway, where one call led to two more calls, and then more. Everyone was ready to talk. One of the people said, “I have been waiting for this call for a year.”

That’s when I found out that many of my sources had already talked to The New York Times on the record over a year ago. So it then became a situation internally where I said, “Oh my God, what I’ve got right now is so different and so far exceeds the type of bullying and anecdotes that we pulled together from these other people that this doesn’t seem like the same story anymore.” And we immediately pivoted it to just a Scott Rudin story.

How long did it take for the piece to come together? It looked like it must have taken months.

No, it came together very quickly.

Really? Wow. It read like it had been brewing for some time. And in a sense it had been, but not on your desk.

You know what, I honestly believe that it may not have happened if it had taken longer. From what I understand, Scott knows when a story’s in the works. But there was no chance for him to lean on sources and say, “Don’t talk to her, I hear she’s writing a story,” because by the time he knew my story was happening, everyone had already talked, everyone was already on the record. I do think it played to my advantage.

The Times report that came out after yours looked like it had been reported over a considerable amount of time, which may lend credence to the idea that there was a big Times story in the works last year that didn’t come out for one reason or another. My sources at the Times have told me there was no single Rudin story that was slated and then killed; and obviously they pushed back publicly on the idea that Rudin’s advertising money had any influence on a story not appearing. But obviously there were a lot of people, as you say, who had spoken to them and not seen a story, so they were primed to talk to you.

And it appears there was nothing journalistically wrong with the story.

I was struck by your recent piece about celebrities being accused of misconduct by dubious online sources, where you spoke to the lawyers for men who’d been given a sort of trial by rumor and the various recourses they have in that situation.

Yes, some of those websites, where there are literally disclaimers that say, “This might be fiction,” are really dangerous. You could have a situation where it’s not even a real person; it’s unvetted. This is very different than a source coming to me as a journalist and saying, “I want to tell my story, but I want to remain anonymous,” because at least the reader can take away that that source, who they might not ever learn the name of, has talked to me and I’ve talked to other people to corroborate what that source said, and we have legal people who are also making sure that this is journalistically sound. Those sites are dangerous because the average reader does not seem to know the difference. I did get some pushback from people who have made claims in the past; they thought it was like me turning against them after doing all this strong reporting. But I see that issue very differently.

In your opinion, why did stars and writers stick with Rudin?

I think at the end of the day, people want to work with somebody who can potentially win awards for them, be it Oscars or Tonys or Emmys. It’s far more important to them than making a studio a lot of money. Once Harvey Weinstein was out of the business, there was nobody even close to Rudin in terms of somebody who could get you into the awards conversation. And if you win an Oscar or a Tony, you’re part of history; that’s different than having a $200 million opening film.

Your follow-up piece went into more detail about how Rudin allegedly covered his tracks for so long. Was that second story a case of having more to say, or just keeping the heat on?

Actually, it was just a matter of so many people coming forward after the initial piece ran that there became a lot more story to tell.

You also reported on his efforts to regroup. To me, the idea of him stepping back from his shows reminds me of the way Trump purportedly “stepped back” from his businesses while he was president. Do you think Rudin is truly divested from all of the productions he indicates he is?

I think the diplomatic answer is that many people who’ve worked closely with him and know him best are very skeptical. You also just have to wonder about—his own work ethic was so intense, like, he slept four hours a night. I wonder how you can go from 100 miles an hour to zero, just even emotionally. Dare I say I am concerned for Scott Rudin and his well-being? There is that part of me where I just kind of think, how would that work?

Well, if you want to flip that thought away from empathy, you could worry about how that incredible energy might instead be channeled into elaborate plans for a comeback. I know you’ll report on that if it happens, but are there currently any plans for another follow-up story?

I think these two pieces are bookends. The first was laying down the landscape, and the second piece was answering, How was this able to go on?

I was amused by the quote from David Geffen in your second piece that Rudin had never raised his voice in his presence—which seemed rich coming from the guy memorialized by Joni Mitchell as lamenting his job dealing with “telephone screamers.” Do you think that culture of intensity and tantrums, of essentially workplace terrorism, is finally starting to change in Hollywood?

I think it’s definitely changing. I think the only difference is that in the past nobody was willing to report it.

Do you feel like your stories are making a difference, and that there are people trying to purge the toxicity and build a better industry?

I think that it is to be determined; I cannot say definitively one way or another yet. There is a huge spotlight on the industry and bad behavior, but it’s also possible people are just going to figure out ways to circumvent the spotlight.

Right. Well, I guess the job is to keep the spotlight on.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org