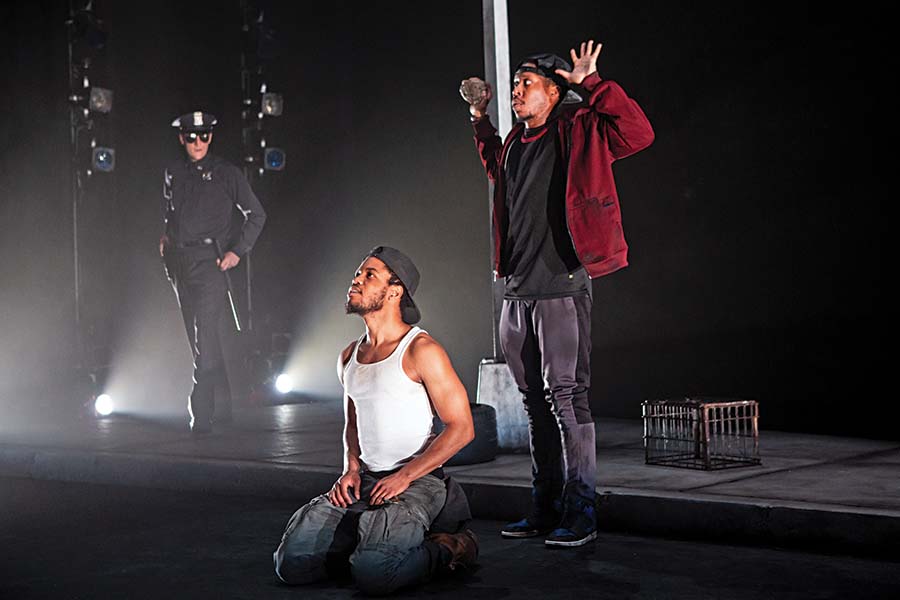

These days, playwright Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu (she/her) is focused on her peace of mind. After a year living through the tumults of the COVID-19 pandemic and some personal strife, she’s ready to celebrate. And she has plenty reason to: namely, the Broadway debut of her play Pass Over in September (previews begin Aug. 4). Inspired by Samuel Beckett’s existential play Waiting for Godot, Pass Over finds two Black men essentially trapped in a “nowhere place” as they try to pass the time and stay out of the crosshairs of an angry police officer.

Nwandu has been living with the play for the last five years, and it has changed with each staging. It premiered at Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago in 2017, in a production captured by director Spike for Prime Video. A year later the play made its Off-Broadway debut at Lincoln Center Theater, but it wasn’t until the beginning of 2020 that discussions about a Broadway run began. Then the pandemic shutdown happened, and along with the rest of us, Nwandu watched as the nation roiled in the turmoil of competing pandemics in healthcare, poverty, and police brutality. Walking the streets of New York and seeing a city still scarred, she recognized that the Broadway version of Pass Over needed to be a rallying cry for unity, liberation, and joy—i.e., one in which the character of Moses doesn’t fall to police violence, as in previous drafts, but lives to fight another day.

American Theatre recently caught up with Nwandu on a busy afternoon as she was getting a manicure between meetings. We spoke about the development of Pass Over, the tradition of the tramp, and her hopes for the future.

KELUNDRA SMITH: You’ve been living with this script for a long time. What made you stick with it?

ANTOINETTE NWANDU: The motto I have adopted for this production is: “It’s above me.” I’m staying with it because the divine spirit continues to keep it in my life. If it was up to me, I would have moved on, but the spirit insists that I stay. I think that until I make the play into the version of itself that people need most—my dream is to make all three versions of the play, which I’m currently referring to as Pass Over 2017, Pass Over 2018, and Pass Over 2021—available to people after this production is over. Each of the three versions is still going to be necessary for somebody.

People often say that Waiting for Godot is a play about nothing. Do you think you’ve changed that notion?

I think I’ve done an okay job, but I also think that people just don’t understand the play. Waiting for Godot is not a play about nothing. I think of my two characters, Moses and Kitch, in the lineage of the tramp. I’m realizing that I need to do some think pieces and essays, because people are stuck in the idea that Beckett is about nothing. Beckett was writing about the tramp. This is when Charlie Chaplin came about; these were white men who were poor and went to fight in World War I and came back with PTSD. You have all of these poor white men—vagabonds, tramps, people who have been disposed of. What war did my characters come through? The war on drugs. The war that’s been waged on Black people since Nixon and Reagan.

When Pass Over premiered in Chicago, there was a lot of controversy around the reviews of that production, especially Hedy Weiss’s review. At any point did you think that response could kill the play’s future?

Yes. Every time I finish a production I think it could be the end. After Chicago, I thought it was done. But Danya Taymor had invited several New York directors to see it in Chicago, and Evan Cabnet [from Lincoln Center] came. Thank God Evan called and convinced me. Lincoln Center was not one of the places I had imagined this show would go up, because Trump had happened.

After that, [producer] Matt Ross and I had our first conversation Feb. 26, 2020. On March 6, 2020, I turned 40; that’s an interesting number in the Bible. I’m writing a play about a plague, and we have a plague. Then, on Jan. 26, 2021, Matt calls me up and says: “Let’s take your play to Broadway.” Like I said, it’s above me.

Performances begin in a few weeks. We don’t know what the Broadway audience will look like when we return, but it may look like it did before the shutdown. Are you grappling with in any way with what it may mean to tell this story in front of an audience that may be mostly white and hence removed from the message?

We are working with REALEMN, which is an all-Black female marketing team. I now have a social media manager who is a Black woman. So we’re going to try to get Black, Asian, and Hispanic people in the audience. As far as the idea that older white people may come in and be removed from the message, I disagree with that quite a bit. The audience for the message is whoever comes in to receive the message. How is it going to be the new world and I still care about your race or your gender? I grew up in the church. Healing and new life are for everybody.

I want to talk about the cost of success, or rather, what success requires. What have you found? What do you need right now?

Do you follow me on Instagram? That’s what it’s requiring of me. It’s requiring me to sit still and allow the fuckery to fall away. When I began the prayer, “Lord, decolonize my life and my mind,” I didn’t know who I was. Whatever this spirit is has seen fit that the thing that I love the most—that has taken most of my energy and focus apart from my work—is no longer in my life. I ain’t got nothing to do with this, and I don’t know if that’s good, bad, or in between. I just know I gotta do this.

There are religious overtones and undertones about passing over as a path to liberation for the men in the play. Do you feel as if you, as a playwright and a person, have passed over? Where do you feel you are in your own passage?

If I were to be so bold as to track my life arc, not to replicate the life of Moses, but it’s like, if you’re going to write about this person in the Bible for five, six, seven years, maybe your life might start to resemble that person a little bit. I would say that definitely in this rehearsal period, I’m going back up to the mount to get the new tablets, because we have the old ones and we don’t need them. You’ve got to lead the people to the Promised Land. The gesture for the new set—I can’t tell you exactly what it’s going to be, but I can tell you that it’s a gesture for a new earth. I’m telling everybody: Come and get your life.

What would you like to see happen for Pass Over after Broadway?

I want it to go to Atlanta, Chicago, Houston, somewhere in the Pacific Northwest, Los Angeles, and then I want it to go to the West End and then the whole world. Because the version of the play that we are making now… When you go through a plague and your mind is right, now all I can see is the version where Moses lives. Black people, BIPOC people, and people of the global majority have seen enough death and violence. Truth be told, if Black bodies are safe, you will be safe too. So now, we’re going to do a version where the Black man lives, and every motherfucker needs to see it. We have mourned enough. This is a time for new life and celebration.

Kelundra Smith (she/her) is a frequent contributor to this magazine.