Now that veteran theatre producer Woodie King Jr. (he/him) has retired as the founder and artistic director of New Federal Theatre (as of the end of June), it’s worth pausing to reflect on his trailblazing, 51-year career as a producer, director, playwright, writer, educator, filmmaker, and actor. He can be directly credited for bringing more than 400 plays to life, not just around New York City, on and Off-Broadway, but around the country and indeed the world.

Several of those productions have garnered prestigious nominations and awards, including the NAACP Image Award and several AUDELCO Awards, in addition an Obie for Sustained Achievement. Theatre Communications Group awarded King with the Peter Zeisler Memorial Award, and Actors’ Equity Association awarded him with both their Paul Robeson Award and their Rosetta LeNoire Award. Last year the Off-Broadway Alliance presented him with a Legend of Off-Broadway Award.

To learn more about his life and career, you stream a 90-minute documentary on Amazon Prime, Juney Smith’s King of Stage: The Woodie King Jr. Story. A few years back, TCG produced a segment about King in its Legacy Leaders of Color video project. King is also the recipient of several honorary doctorates from Wayne State University, College of Wooster, and CUNY/John Jay College.

It’s all quite impressive, but in going over his half-century odyssey of professional theatre producing with King, as I did on a sunny Saturday in early June over Zoom, there can still be fresh surprises. I’ve had the pleasure of knowing him for nearly two decades and we’ve done a handful of shows together over the years, so I thought I knew all his career highlights. And then he casually dropped the name of Langston Hughes.

MARSHALL JONES III: Wait, you knew Langston Hughes?

WOODIE KING JR.: Yes. Okay, well, he published one of my short stories.

What? How cool is that?

Well, I’m from Detroit, and I was in the library every day reading Shaw, Ibsen, short stories. A librarian told me about there was E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts next door, a wonderful collection of resources about Black theatre artists. That’s how I learned about the Federal Theatre Project during the New Deal under FDR. So one year, the Hackley Collection invited Langston Hughes to speak. That’s how I met him. And Langston Hughes published one of my short stories. That gave me so much confidence and everything. Then I came to New York and I adapted one of his plays.

❦

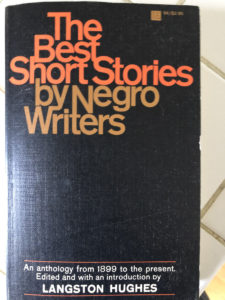

My fingers quickly grabbed the mouse to visit to Amazon, and sure enough, there it is: The Best Short Stories By Negro Writers: An Anthology From 1899 to 1967, edited by Langston Hughes. King’s short story is nestled among several literary giants of the 20th century: Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Alice Walker, Gwendolyn Brooks, James Baldwin, Alice Childress, Ralph Ellison.

My fingers quickly grabbed the mouse to visit to Amazon, and sure enough, there it is: The Best Short Stories By Negro Writers: An Anthology From 1899 to 1967, edited by Langston Hughes. King’s short story is nestled among several literary giants of the 20th century: Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Alice Walker, Gwendolyn Brooks, James Baldwin, Alice Childress, Ralph Ellison.

The short story, entitled Beautiful Light and Black Our Dreams, is essentially a romance, in which a young Black man goes on a romantic journey dreaming about “Joanne.” King’s imagery is both lushly poetic and harshly realistic as the hero grapples with the devastating effects of racism. Yet, in spite of his racism of the era—a lot of which persists to today—he develops a fondness for Joanna.

❦

JONES: You were published by at such a young age with all those literary giants. What was that like?

KING: To be published by Langston Hughes was very special. But I had no idea of who the other writers would be included at the time.

What was Langston like?

We met maybe 10 or 12 times at his place on 127th Street, and oh, man, it was like heaven. I adapted one of his plays, The Weary Blues, at Lincoln Center Museum for the Performing Arts (not the Lincoln Center Theater). He introduced me to people. He took me to plays, all these plays being done all these years ago with Blacks, and I didn’t have to pay because I was with Langston. That was wonderful, Marshall. Wonderful. You don’t have those kinds of people now.

I see what you’re saying. But I will also say that now kids are going not to library collections but to Google to study the career of Woodie King Jr., and they are inspired by you.

Yeah, we didn’t have Google back then. To study and learn you had to go the library. We had to go do the work. I just wish I had kept those little checkered notebooks I used. I wrote so much notes and more. But when I moved from Detroit, of course, I threw them away. I left thinking I wouldn’t ever need them.

Let’s talk about your accomplishments—

My greatest accomplishments was taking what I’ve learned, watching and listening, especially music, and that music being rhythm and blues—man, what those singers could do in three minutes on a record. That got me thinking about trying to inculcate that into plays and finding that same rhythm, like a record, and being able to transfer that to the stage.

That’s really deep. That is similar to August Wilson and how the blues inspired him.

August and I used to talk a great deal about how you come to this music in plays. I came to it by listening. When I was 12 or 13, I listened closely to the Diablos, the Harptones, groups like that. There was something in those records that made you move a certain way, that made you do things a certain way. When I came to do plays, I looked for that. And somehow when you got that rhythm right, those plays were absolutely amazing. Because you could stand at the back of the theatre and see people standing, cheering. I wrote about it in a book, you know.

Yeah, The Impact of Race: Theatre and Culture.

I wanted to tell stories that contained the rhythms that only Black people have. And where does that rhythm come from? It can’t be developed by white people. You understand?

Yes, I do.

I obviously love great gospel singers and shows like Gospel at Colonus. Those singers were brilliant, you know? But the soul, the rhythm—Lee Breuer [the show’s creator, who was white] can’t reproduce that. I wrote about this in a lot of short stories called Searching for Brothers Kindred. And that search will never stop. Because all of our music—like gospel music, and especially Sam Cooke—our music stirs the soul. I used to listen to them records over and over again. And it’s there, Marshall, it’s there! But where does that come from? Almost every Black person in the North migrated from somewhere in the South, or some of our other mothers, grandmothers, great, great, great grandmothers, came out of slavery into the urban North. The Great Migration. So being able to translate that into theatre and being able to really work on it—it’s beautiful, man. What can I say?

It’s great how music impacted your artistry. Do you think it has something to do with being from Motown?

Motown hadn’t started yet. Or maybe it did, but I didn’t know. I was in theatre trying to learn how to act. I was willing to do anything to act. I was going to Wayne State after I graduated high school. I worked from midnight to 8 a.m. at Ford Motor Company, and at 10 a.m. I would go to acting school until 1 p.m., then after class come home and sleep, you know. This was in the ’50s. I graduated high school in 1956.

My mom graduated ’57, so y’all the same age.

[Laughs] Yeah, I was doing my thing, listening to music. But the Motown people came later. I knew all the people that came to Motown. I knew Smokey [Robinson], I knew Bobby Rogers [founding member of Smokey Robinson’s band, the Miracles]. I knew most of those people, because there’s only so many places you could go to skate and dance. Madison Ballroom [Laughs]. Mickey Stevenson, he was Monte’s brother; Monte was an actor, a friend of Ron Milner’s. Without Mickey, there would be no Motown. I even did a play about Mickey, I put his music together in a show. And you know he wrote “Dancing in the Street”?“Dancing in the Street” has been viewed as an anthem for us, but some people say it was just about dancing.

No, there’s a message in that song. It was ’64. It was early Motown. Mickey Stevenson was the A&R man who didn’t know anything about A&R [laughs]. He just went in and tried to do what was missing.

Do you have the script for that show in a box somewhere? The scripts of all of your plays would probably fill up an airplane hangar.

Yeah, well, I can’t sing. I was not a dancer. Listening to the music, the rhythm, the Temptations and Sam Cooke. Oh my God. Yes. You know, the Temptations could do spirituals. They could do rhythm and blues. They could do it all.

❦

I left Detroit after I saw the touring version of A Raisin in the Sun. I was already interested in theatre. I was going to Wayne State University, and we rehearsed scenes in the basement of the school. I got cast in The Adding Machine by Elmer Rice. I was working like 24/7 between work and school.

So you were a theatre major at Wayne State?

Ah, yes, a theatre major. But there was no theatre. So that’s why you’re in the basement! [Laughs]

You were there around the time of Von Washington. He’s the father of my ex-wife.

Von and I did like two or three shows together. Oh man. His voice. He’s got a great voice.

It’s all connected, man. The people in Black theatre, we’re a small and mighty group, but we’re all connected.

I think so. The Black Arts Movement was coming into existence at a rapid pace. Amiri Baraka and I got connected up in Harlem with the Black Arts Repertory Theater. But the Black Arts Movement was national: It was happening all over Los Angeles, the South, the North, New York, San Francisco, all these places, right? Ed Bullins was from San Francisco. Ron Milner from Detroit. So this Black Arts Movement is similar to the music scene, the same as Black theatre. This reaffirmed everything I felt strongly about, the reaffirmation of one’s identity. The Black Arts Movement put a stamp on your identity. It said, This is who I am and this is what I want.

Like, what I got? One degree and five honorary doctorates. This is who I am, I’m not going to change. We paved the way for young people who are coming into theatre today. But I did not want to work for people; I didn’t want to work every day for somebody else. It was not about money, you know.

What comes to your mind looking back?

To just be an actor, man. Working as an actor. When I saw the touring version of A Raisin in the Sun when it came to Detroit—oh, I had never seen anything like it. And I said, “Oh my God, this is something and I want to do that.”

I remember you telling me that story. It changed your life.

Yes, it did.

❦

When I teach Black theatre history, I point out that every major Black theatre company in the U.S. was started by subsidy. You got a large subsidy through Henry Street. How did that come to be?

I was running a training program called Mobilization for Youth. It was for young people 16 to 21 years old. Bertram Beck asked me to come over to Henry Street with the program in 1969-70. So I went over there with him. And then he said, “Look at this playhouse here,” a stunning theatre that used to be the home of the Neighborhood Playhouse.

The Neighborhood Playhouse where Sanford Meisner taught?

Yes, that Neighborhood Playhouse. 466 Grand Street. Henry Street Settlement owned that building. So my arrival with Bertram Beck gave me an opportunity to not only have a training program, but the start of a theatre. I named it the New Federal Theatre, which came out of the old Federal Theatre run by John Houseman and Hallie Flanagan and Orson Welles. It was government-supported from 1935 to 1939, and it had a Negro Unit. The old Federal Theatre did some incredible work, including the Voodoo Macbeth up in Harlem. That was groundbreaking.

How do you decide what plays to produce?

Well, I knew what I liked. And I know how to read a play. I’d read five or six plays a week.

The play would speak to you?

Yeah, the rhythm. Find the rhythm within the play. And the lead characters, what are they searching for? What is their identity? The characters leap off the page, like in Ed Bullins’s The Taking of Miss Janie; Wesley Brown’s Boogie Woogie and Booker T; The Meeting by Jeff Stetson.

How do you select directors?

Well, when I’ve seen something they’ve done and I like it, we’ll talk about it over coffee. And then I’ll suggest there might be a play I have in mind for them to direct. Usually, by the time they read the play, and tell me they want to meet with me about it, I already know if I want to use them or not. [Laughs]

You’re also a director yourself. How have you been able to balance that?

As a director, a regional theatre hires me. Like the play Home by Samm-Art Williams, I did it at about five theatres around the U.S. I mostly produce Off-Broadway. But I did a couple plays on Broadway: I directed Checkmates on Broadway and What the Wine-Sellers Buy.

I like reading the play over and over again, and knowing the actors I think should do it. Then you go looking for some top producers so they’ll put up the money. In the old days it was maybe the Nederlanders, when they were alive, or the Shuberts. Nelle Nugent and Liz McCann. They had these theatre chains, and if one of them didn’t want to produce my play, then, well, you know, you can go to the other three or four.

Have you ever come across a script that you want to produce and know that you’re not the most appropriate director?

Yes, man. Like Looking for LeRoi by Larry Muhammad. This is a play about Amiri Baraka. Now, I love LeRoi Jones—I knew him back when he was LeRoi, not Amiri. But I knew I had to have a woman direct it, so I called Petronia Paley. Petronia, you know, she’s particular, and that’s what the play needed. And I love the works of Elaine Jackson, but I only directed one of her plays, because it needed the feminine perspective, right?

So it was a gender issue?

No, no—it needed something I didn’t have. You know, the deal with that rhythm. Like, I love Lynn Nottage. I love everything she writes. But when she writes anything more than six, seven characters, I just can’t deal with it. And Dominique Morisseau, even her two-character plays are excellent. Excellent, man. I can’t direct them, but I love to produce them!

❦

What did you think of Douglas Turner Ward’s op-ed in The New York Times back in 1966, “American Theater: For Whites Only”?

I didn’t think the Times would print it, but they did. And, sure enough, the Ford Foundation called them and gave them all that money.

Were you close with Doug?

Oh yeah, we were friends. Doug, and Robert Hooks, and Gerald Krone.

Did you ever co-produce work with the Negro Ensemble Company?

No, we never co-produced. They had a company of 13 members, and those 13 members were just fine actors. Like Barbara Ann Teer. I worked with Barbara when she was working with the Group Theatre Workshop. Then they transferred them over to form Negro Ensemble. And I worked with Robert Hooks on two or three movies. Not big roles, but tiny roles.

See, I’m glad you mentioned that—with Dr. Teer’s National Black Theatre, Doug at the NEC, Rick Khan at Crossroads, Lou Bellamy at Penumbra, and others, in Black Theatre, y’all are more than just the artistic director, right?

Right. We are the organization. As a matter of fact, the artistic director has got to change direction or do something else. Lloyd Richards directed a play for us called Christopher Columbus, about Columbus and the discovery of America. It was so eye-opening. Lloyd found things in that play, man! The difference in the artistic input was amazing. And this play was by Nikos Kazantzakis, the famous Greek writer. People don’t know he wrote a play. I got the rights on it and I did it.

You called Lloyd to direct and he said yes.

[Laughs] Yeah, I used to clean Lloyd’s studio when I was taking acting lessons. And I did My One Good Nerve by Ruby Dee. I had this white director, the old actor Charles Nelson Reilly.Oh, he directed Robeson too.

Yes, yes. You know, New Federal has crossed all color lines with all minorities, ethnic minorities, and all major artists in the American theatre. Award winners to non-award winners, so I’m very, very pleased with that.

What about Denzel Washington?

I did a play written by Laurence Holder, When the Chickens Came Home to Roost, and it was the first major role Denzel Washington did in NYC. The play was about Malcolm X. Man, the audience cheered when he walked onstage because he had the Malcolm walk and the Malcolm accent. Denzel couldn’t have been no more than 22, 23 years old. This was 1980. [Denzel was a very young-looking 26 that year. – Ed.] And then he got an agent, and out of that he got St. Elsewhere, and he went on and on. He and I used to be coffee buddies. Early in his career, he used to donate to New Federal, but he doesn’t give now.

With actors like that, you just know. Denzel just had it. Now, when an ordinary actor named Vin Diesel—

Wait, the Fast and Furious Vin Diesel?

Yeah, the action guy in crime movies. He made it. Vin’s stepfather, Irving Vincent, was an acting teacher here and directed shows. Vin was a little kid running around the theatre while his father was rehearsing or teaching. I watched him grow up, then he started making films. He wrote and directed a film called Multi Facial. I don’t know why, but I gave him $500 or $1,000, just wrote a check to help him finance the film. In 1995 the film went to Cannes. He became famous three years later with Saving Private Ryan. Vin sent me $5,000 each year. That’s how you do it.

Yeah, giving back. What about Chadwick?

Now, Chadwick Boseman. He did Ron Milner’s last play, Urban Transitions, with us in 2002. He won an AUDELCO Award for his acting. And, like Denzel, he then got an agent and his career just took off. And just like Denzel, Chadwick could turn on a dime and be a killer with his acting. He had unbelievable knowledge of self and the human spirit. You know, Marshall, actors like Denzel and Chadwick could do it all, man. And at such a young age. I wish I had their courage. But when I was that age, there was no place for me to go. I had to create everything.

❦

You hand-picked Elizabeth Van Dyke to be your successor. Why?

Well, you can’t you just hand over to anyone. She’s ready, definitely. And you want to hope that she’ll go on for 10 or 20 years or more. She’s been around New Federal, so she knows how we work, how we operate, and that’s important.

Even though you’re retiring from New Federal, you’ll still be on the board. There’s still a lot on your plate.

During the pandemic, we’ve been working. We’re doing readings on Tuesdays in June. We’ve done Black History Month. We’ve done the gala, our 51st anniversary celebration. And while we’re doing this, I got to learn how to operate Zoom and all this stuff. At least Elizabeth Van Dyke is right here learning with me. So the future is going to look different. I told you I went to event and I had to stand. After about an hour I couldn’t stand no more. You can’t run a theatre if you can’t stand for two hours. I watched directors sometimes sit in one spot and direct a play. You cannot direct that play like that; you gotta jump up and move. So I will not have a fishing pole, sitting in one spot trying to catch a trout.

[Laughs]Now the film that my attorney asked me to work on is for Netflix. It’s called Bud, not Buddy, an adaptation of the historical fiction novel about a 10-year-old boy’s journey during the Great Depression. I’m the associate producer. My role is to suggest Black voices and things like that. And I know they goin’ to listen to me. In terms of the book I’m putting together, it’s not a memoir, but it’s going to tie into the Black Arts Movement, and that’s going to tie into how I see the future of African Americans in the commercial theatre.

OK. I’ll buy that book.

Great. Third World Press is going to publish it.

Incredible, Woodie. Is there anything that you would like to add that I didn’t cover?

I was around before American Theatre magazine existed. Peter Zeisler was the head of TCG and we were good friends, you know. And when the magazine came out, I was absolutely surprised that it was so wonderful. But it took a lot of years before they got any Black writers, and I could not believe this. TCG was dealing with all these regional theatres. And I said, Oh, wow, it’s like if I put out a magazine, I would definitely feature everybody: Blacks, whites, everybody. But they didn’t hire any Black writers back then, so I’m so glad that you are writing.

Marshall Jones III (he/him) was producing artistic director of Crossroads from 2007 to 2019. Since 2002, he’s been professor of Theatre at his alma mater, the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University.