This is the second in an ongoing series, the Tapestry of American Black Theatre, which is chronicling the too often forgotten contributions of Black theatremakers in the U.S. The first article in the series told the story of the Negro Ensemble Company. Future articles will explore some of the many Black Theatre organizations, leaders, performers, and work. There are currently nearly 90 Black theatres in the United States.

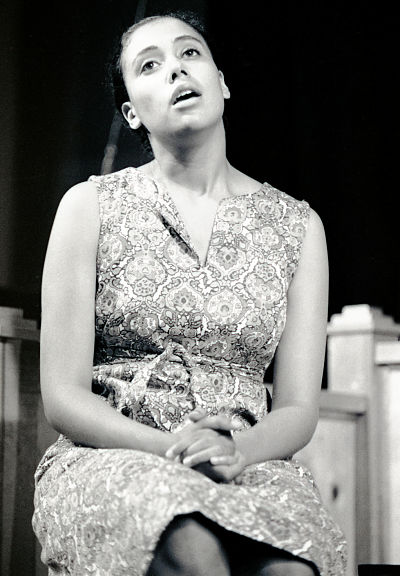

Years before she became a TV star on Room 222 and In the Heat of the Night, Denise Nicholas found herself in Jackson, Miss., in June, 1964, during a busy time. It was the beginning of official U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, and just days after three Civil Rights workers went missing; their bodies would soon be discovered. Arriving at the request of Gilbert Moses, one of the founders of the Free Southern Theater (FST), she was there to educate and help with voter registration on behalf of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), where Moses was a long-time staff member.

What Nicholas saw was a huge departure from her upbringing in Detroit and her classes at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Yes, she had seen discrimination both heavy and light. Her dorm roommate had taken one look and announced she’d only seen Black people in maids’ uniforms. But in deeply segregated Mississippi, schools did not intellectually nourish black children, and mainstream TV, radio, and other media failed to deliver information about the real conditions of life for African Americans. Whites lived comfortably in Mississippi, but for Black people it was a feudal Jim Crow society offering few options beyond picking cotton and serving whites. Most recreation centers, movies theatres, and YMCAs were off limits to Black people. As Moses stated, “Mississippi’s closed system effectively refuses the Negro knowledge of himself.”

Such an environment was not welcoming to his theatre either, Nicholas recalled, so they learned how to inoculate themselves—to get accustomed to whatever level of terror they could take and still keep going. For example, in Jackson, they had to sleep on the floor, because the Klan often roamed the streets at night, firing their guns, in the places they stayed.

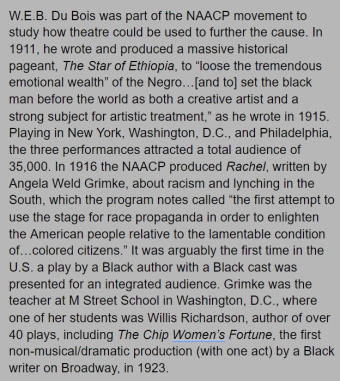

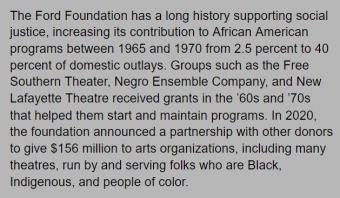

Moses had started FST in 1963 with SNCC and NAACP member Doris Derby and SNCC member John O’Neal. SNCC’s prospectus included the goals of overcoming “the caste system in a cultural desert” by helping to create patterns of creative and reflective thought, both of which had been as restricted for Blacks as their access to other social and material goods. FST’s goal was to start a Black theatre with Black artists. After convincing Richard Schechner, then a professor of drama at Tulane, to help, the founders held a three-day marathon meeting to make plans. The decision was to produce political and moral dramas by James Baldwin, Bertolt Brecht, and Langston Hughes, as well as musicals, comedies, and improvisations, and to stage their work in churches, halls, even fields—any place suitable for an audience. Participants would be local residents, as well as professional actors. FST realized that protest was not enough; there was an educational and cultural gap to be closed. SNCC helped create a permanent resident company in Jackson, with mobile units travelling to other locations. A Ford Foundation grant helped them achieve their goals

Moses had started FST in 1963 with SNCC and NAACP member Doris Derby and SNCC member John O’Neal. SNCC’s prospectus included the goals of overcoming “the caste system in a cultural desert” by helping to create patterns of creative and reflective thought, both of which had been as restricted for Blacks as their access to other social and material goods. FST’s goal was to start a Black theatre with Black artists. After convincing Richard Schechner, then a professor of drama at Tulane, to help, the founders held a three-day marathon meeting to make plans. The decision was to produce political and moral dramas by James Baldwin, Bertolt Brecht, and Langston Hughes, as well as musicals, comedies, and improvisations, and to stage their work in churches, halls, even fields—any place suitable for an audience. Participants would be local residents, as well as professional actors. FST realized that protest was not enough; there was an educational and cultural gap to be closed. SNCC helped create a permanent resident company in Jackson, with mobile units travelling to other locations. A Ford Foundation grant helped them achieve their goals

FST’s first production, In White America by Martin Duberman, was a documentary play which, according to The New York Times, “creates a historical mosaic of the lives of African-Americans from slave days in the early 1600s through the integration of public schools in the ’50s.” It toured 16 towns, with farm and country people attending; performances were held in the afternoon so that audience members had time to get home by dark. In Greenwood, Miss., the movement attorney Len Hold was told, “They were telling my story on that stage…and telling it like it really is.”

Performances were held mostly in churches, but also outside. Nicholas, who became one of FST’s leaders after Derby departed for academia, recalled one performance of Ossie Davis’s Purlie Victorious next to a cotton field, in which the Uncle Tom-like character of Gitlow came running onto the stage from that cotton field, sending cotton balls flying all around. The audience broke out in hysterical laughter.

Performances were held mostly in churches, but also outside. Nicholas, who became one of FST’s leaders after Derby departed for academia, recalled one performance of Ossie Davis’s Purlie Victorious next to a cotton field, in which the Uncle Tom-like character of Gitlow came running onto the stage from that cotton field, sending cotton balls flying all around. The audience broke out in hysterical laughter.

FST wanted people to feel they were not isolated, that they were part of a coming moment, and to help them keep their fear in check, as their lives were threatened on a day-to-day basis by bullying and brutal violence. One venue, in Mileston, Miss., in Holmes County, was a partly completed community center that had recently been bombed by white terrorists.

After the shows there was a discussion, often covering the subjects of voting rights, what theatre meant to the audience members, and how they interpreted the play they had just watched, considering what was going on around them. After one performance of Waiting for Godot, which was sometimes performed in whiteface, Fannie Lou Hamer led the post-show discussion; one audience member expressed perplexity at Samuel Beckett’s absurdist drama. Recalled Nicholas, “Hamer just looked at them and said, ‘I guess we know something about waiting,’ and they all responded with, ‘Don’t we!’”

Others from up North joined, including Roscoe Orman, who was later heavily involved in the New Lafayette Theatre, and would become widely known as Gordon on Sesame Street. Another Northerner was Erik Lewis, who went from mobilizer of a youth theatre on New York’s Lower East Side (and a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War) to technical director for FST, building portable sets and making masks and puppets out of papier-mâché and clay for children’s workshops. One production took place right after a hurricane, to help the kids deal with the trauma. Lewis, who became lifelong friends with Nicholas and Orman, was recruited by Moses—a man, in Lewis’s word, with such power he was like “a hurricane packed into a body.” The shows they put on were filled with such dynamism and engagement that quite a number of young audience members, wanting to be part of FST, followed them from town to town.

Though these theatre offerings provided relief and entertainment to audiences, it was not all fun and games. The FST and SNCC people were putting their lives on the line. Said Orman, who ended up touring for two years, “It was really dangerous. People were getting killed and attacked, and we had some pretty close calls ourselves.” Because of threats from the Ku Klux Klan, an organization called the Deacons for Defense and Justice protected them, standing at the gates and in the fields with rifles. The Deacons were Black men whose purpose was to defend the African American community and Civil Rights workers. The group started in Bogalusa, La., after decades of lynchings, bombings, and police brutality faced no legal consequences. In 1965, FST relocated to New Orleans, where they had slightly more freedom than in other parts of the Deep South.

Whereas Black theatre in the South was in need of basic access to cultural activities, as well as discussion and debate on socioeconomic and racial issues and general consciousness-raising, Black theatre in the North was still influenced by the intellectual ferment and political empowerment of the earlier Harlem Renaissance. One could say that the point of Black theatre in the North was internal, embodied in the play and the culture, while the point of Black theatre in the South was external, meant to develop the community and encourage voter participation.

Nevertheless, Black theatre without walls wasn’t just a phenomenon in the South, but also in New York City. Playwright, director, and actor Roger Furman, who had been part of the American Negro Theater (ANT) in the 1940s, initiated a new venture in 1964 called the New Heritage Repertory Theatre (NHRT), with the mission to sustain and preserve classic Black theatre works. Furman began what was originally a street theatre company as a supplementary activity to his job at the federally financed Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited. HARYOU was an organization of social activism started by the married couple Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark and Dr. Kenneth Clark, the first African Americans to receive doctorates in psychology from Columbia University. Kenneth Clark was well known for his testimony in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, in which he described the research he and his wife had conducted, showing differently colored dolls to African American children; the children all preferred whiter dolls, causing the Clarks to conclude “prejudice, discrimination, and segregation” damaged self-esteem and created a sense of inferiority in Black children.

Nevertheless, Black theatre without walls wasn’t just a phenomenon in the South, but also in New York City. Playwright, director, and actor Roger Furman, who had been part of the American Negro Theater (ANT) in the 1940s, initiated a new venture in 1964 called the New Heritage Repertory Theatre (NHRT), with the mission to sustain and preserve classic Black theatre works. Furman began what was originally a street theatre company as a supplementary activity to his job at the federally financed Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited. HARYOU was an organization of social activism started by the married couple Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark and Dr. Kenneth Clark, the first African Americans to receive doctorates in psychology from Columbia University. Kenneth Clark was well known for his testimony in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, in which he described the research he and his wife had conducted, showing differently colored dolls to African American children; the children all preferred whiter dolls, causing the Clarks to conclude “prejudice, discrimination, and segregation” damaged self-esteem and created a sense of inferiority in Black children.

One young man whose self-esteem was boosted by the theatre was Voza Rivers, a shy young man in Harlem who, when he was asked what he thought about the issues and incidents of the day, struggled with answers. So he signed up for a public speaking course at the Harlem YMCA, and his first guest was speaker was Roger Furman, who talked about the important role arts and culture, and particularly theatre, can play: It can help develop character and heal wounds. Furman shared his gratitude for having been part of the American Negro Theatre as a young man, and how he wanted to start a company based on the ANT model. Soon many of his students—who in addition to Rivers included Ruby Dee, Sidney Poitier, and Harry Belafonte—began working with Furman to put on plays in a little library on 130th street (currently the location of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

One young man whose self-esteem was boosted by the theatre was Voza Rivers, a shy young man in Harlem who, when he was asked what he thought about the issues and incidents of the day, struggled with answers. So he signed up for a public speaking course at the Harlem YMCA, and his first guest was speaker was Roger Furman, who talked about the important role arts and culture, and particularly theatre, can play: It can help develop character and heal wounds. Furman shared his gratitude for having been part of the American Negro Theatre as a young man, and how he wanted to start a company based on the ANT model. Soon many of his students—who in addition to Rivers included Ruby Dee, Sidney Poitier, and Harry Belafonte—began working with Furman to put on plays in a little library on 130th street (currently the location of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

When Furman launched NHRT in 1964, he managed to bring on board the two ANT founders, Abram Hill and Frederick O’Neal. And two years later, when federal anti-poverty programs began, NHRT got a $48,000 grant to teach theatre to young people, and the program got written up in The New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, The Daily News, and even a Boston newspaper.

Though he was initially not interested in theatre—he had come for the public speaking only—Rivers had become a volunteer at the theatre, helping out as the box office person, the chauffeur, the maintenance guy. One day Furman sat Rivers down and commended his dedication and his skills in so many areas. How would he like to be a partner, running the business side, so that Furman could concentrate on the artistic elements? With this new configuration, the pace at NHRT picked up. The company produced more than 35 plays, including an immensely popular revival of Abram Hill’s On Strivers Row, whose title refers to an upscale block in Harlem. It became the theatre’s longest-running show up to that time.

When Furman died in 1983 at age 59, the board asked Rivers to take over, and he agreed. The name was changed to New Heritage Theatre Group (NHTG), and its repertoire expanded, as they worked with fifth-generation Harlem resident and award-winning actor and director Debra Ann Byrd, who started the Harlem Shakespeare Festival. As Byrd noted, “I decided, I am going to start a theatre company where classically trained actors of color get opportunities to perform whatever classics they want to perform.”

Branching out beyond Furman’s vision of highlighting African American literature and culture, Rivers expanded beyond Harlem and brought in South African “artivism” writers who were fighting apartheid and using the theatre to connect with communities and motivate people. His first venture was to bring Woza Albert! (translation Rise Up, Albert)—a present-day imagining of what might happen if Jesus showed up in the apartheid South Africa, which was a hit with largely white audiences at the Lucille Lortel Theater in the West Village in 1984—to Harlem for a limited run. Downtown theatre royalty came to sit alongside everyday folks in folding chairs when there were no seats left.

Rivers convinced Mbogeni Ngemi, one of the show’s two actor-writers (the other was Percy Mtwa), to return to South Africa and write another play, which Rivers would produce. But when it came time for Rivers to fly to South Africa to see the new play, he could not get a visa, because, as a producer of Woza Albert! in the U.S., he was now considered part of the anti-apartheid movement by the South African government. Rivers had to listen in by phone as the troupe rehearsed a new musical about the Soweto riots and the 1976 massacre. Hearing the energy over the phone, he decided to bring the show to Harlem, sight unseen. There were a few complications along the way: He had assumed there might be 10 actors in the show, but the writers told him the number was 35. Rivers went to funders and to the NY Council for the Arts, and most of them thought he was crazy to want to bring 35 South African actors over to perform in a 99-seat theatre.

But Sarafina! opened in the small theatre on 130th Street in 1987 and ran for five sold-out weeks. Poitier was in the audience, as well as Miriam Makeba and Quincy Jones. Sarafina! moved to Lincoln Center Theater’s Off-Broadway space, where it ran from September 1987 to January 1988, then to the Cort Theatre on Broadway, where it ran from January 1988 through July 1989 (for a total of 597 performances) and was nominated for four Tony Awards. After Broadway, Rivers worked with the South African creators to put together an international company that toured Sarafina! though Europe, Africa, and Japan for 10 years. When Broadway’s The Lion King opened in 1997, a number of Sarafina! actors were chosen for key roles.

Rivers also worked with the Public Theater and Woodie King Jr. of the New Federal Theatre (to be featured in a future article in this series) to produce Roger Guenveur Smith’s one-man show, A Huey P. Newton Story. In the audience was Spike Lee, who adapted the play into a successful film in 2001. Also in 1997, IMPACT, a youth division of NHTG, was established by writer, director, poet, and activist Jamal Joseph, who has since educated over 1,000 young people between ages 12 and 19. Further work by the NHTG includes a reading series and film festival.

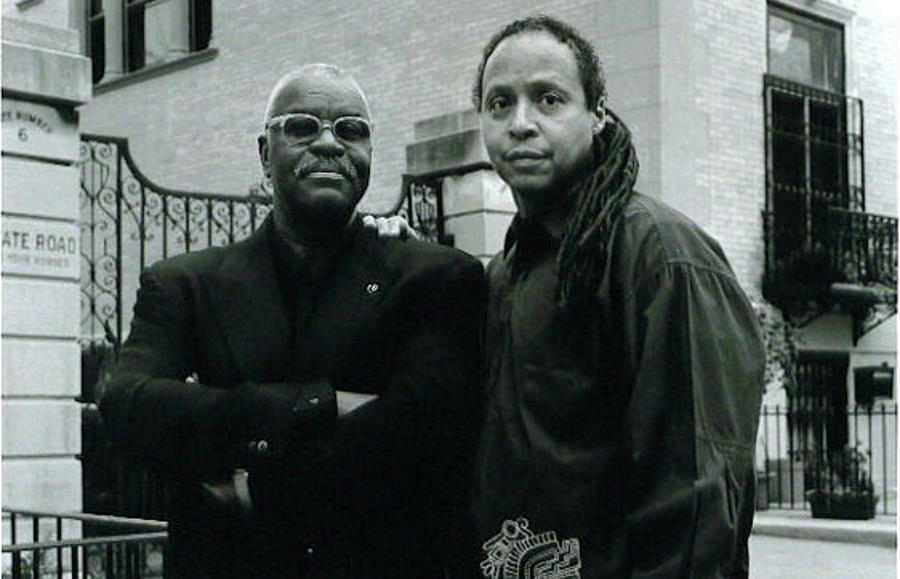

What is the secret to Rivers’ success? He modestly says, “I’m not that brilliant, but great stories or historical scenarios have a way of moving me. There’s something in my DNA that connects me with the content and the important message.” In 2021, the New Heritage Theatre Group celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Hinton Battle is a three-time Tony winner whose Broadway credits include The Wiz, Bob Fosse’s Dancin’, Dreamgirls, Sophisticated Ladies, Chicago, Miss Saigon, and The Tap Dance Kid. He is currently the co-founder and director of the Hinton Battle Dance Academy (HBDA) in Tokyo.

Dorothy Marcic, Ph.D., is a Columbia University professor, Fulbright Scholar, and playwright of Respect: The Musical and Sistas: The Musical, the longest-running African American musical Off-Broadway. She’s the writer of 21 bestselling books and award-winning screenplays, and is co-creator of the Wondery podcast Man-Slaughter.

Kimberley LaMarque Orman, a professor at Fordham University and executive producer of the video series Fordham Road, has produced, acted, and directed in a variety of productions across the U.S., including Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Jar the Floor, Macbeth, In the Blood, Blues for an Alabama Sky, Romeo & Juliet, Three Sisters, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, and The Old Settler.