Something was behind me. In my bedroom.

In the dark.

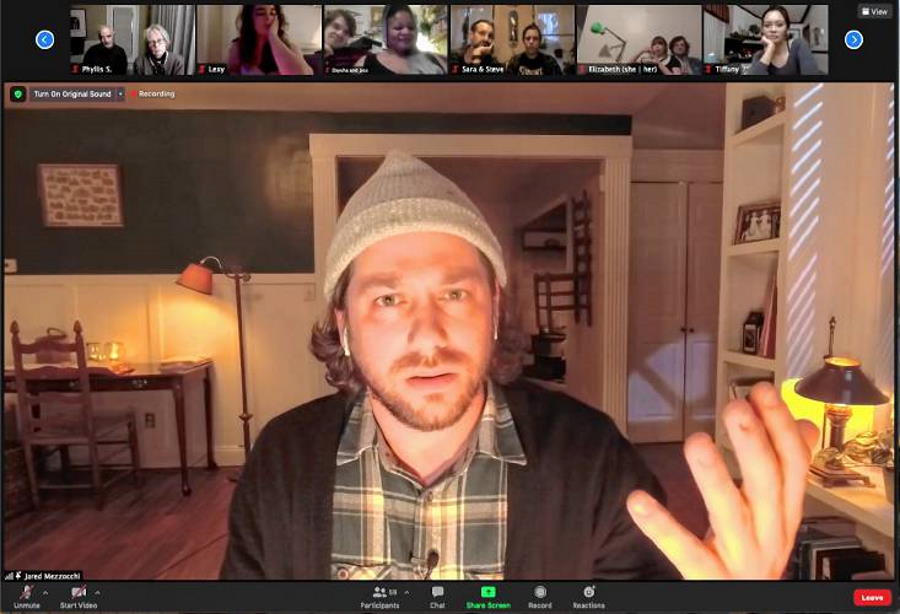

When the Geffen Playhouse production of Someone Else’s House began at 8:30 p.m., bright daylight still snuck through my shades. My laptop, usually reserved for work and doom-scrolling, was surrounded by flickering candles and a few other eerie online-show accoutrements that arrived in a package on my front steps a week earlier. My computer’s camera was on (a requirement), and, staring straight at me through the screen, Jared Mezzocchi (he/him) told the real-life story of his family’s encounter with a haunted house.

Before I noticed it happening, it was pitch-black outside. My room was filled with shadows, and I whipped my head around every time I saw a shadow move. After 15 months spent fighting the emotional flatness of spending the bulk of my time at home, these unexpected adrenaline spikes felt like a defibrillator to the spirit, and achieved something that few—if any—traditional, in-person theatrical experiences have ever given me: I was afraid.

Shared space, the energizing power of live theatre, can be a neutralizing force when it comes to fear. When you can glimpse a glowing exit sign in your peripheral vision, it’s hard to believe in real danger. But innovative artists like Mezzocchi are tapping into remote theatre’s unique capability to help us suspend our disbelief, not to mention a zeitgeist-y hunger for genuine, visceral thrills.

Mezzocchi spent the early months of the pandemic deploying his experience as a theatre director and multimedia designer on projects such as Sarah Gancher’s lauded Russian Troll Farm, integrating design tech into the brave new world of online theatre.

He started crafting a pitch for the Geffen while ensconced at the MacDowell Colony (“excruciatingly haunted” was one phrase he came up with) in the woods of Peterborough, N.H. “Is it weird that we’re talking about springtime and I can’t help but think about ghosts?” Mezzocchi remembers texting his agent. “And she was like, we are surrounded by death right now. I don’t think it’s weird at all.”

In crafting the Zoom iteration of this story, Mezzocchi and director Margot Bordelon (she/her) made a deliberate choice to steer Someone Else’s House away from the familiar horror traps of camp and spectacle, both for structural integrity and out of respect for Mezzocchi’s family experience. “Even though Jared is a video genius, the main spectacle in this piece is the story,” Bordelon said. “You can add a lot of splashy design to something, but if it’s not a strong narrative, then who cares?”

The audience experience of Someone Else’s House felt deceptively lo-fi—which was in its own way a heavy lift. Indeed, said Mezzocchi, “This was one of the most technically challenging pieces I’ve worked on this whole pandemic, because it could never feel like the technology was in front. It’s hard to remain in a subtle, nuanced space over Zoom.”

I won’t spoil the narrative, because I firmly believe experiences like this should remain un-Googleable, in case they return in a future iteration. Suffice it to say, Someone Else’s House centers on a New Hampshire house and is bolstered by reams of Mezzocchi’s historical research (but I’m not fact checking). Watching the candlelight play across the faces of my fellow audience members, wherever they may have been, we helped to tell the story, and noticed one another noticing visual effects so subtle that at first we barely recognized they were happening.

When the shock and awe hit, not only was the jolt of adrenaline a sort psychic umami bomb. There was also something powerful about a feeling of collective survival, in a story I was part of, as we are all surrounded by death in real life.

Audience members’ mileage may vary when it comes to individual scare tactics, but as Mezzocchi put it, “There’s real catharsis in telling ghost stories right now, because we, as an [American] culture, have no idea where to put 600,000 souls lost.”

In an unofficial text-message poll of theatremakers I know, the most frequent response to my question, “Have you ever been genuinely scared at the theatre?” was a version of, “Do you mean scared scared, or like…existential dread?”

Many respondents had experienced horror, the genre; far fewer horror, the feeling. Proposed examples were similar because there are so few: the ending of The Pillowman, a particularly bloody Titus Andronicus. Bordelon named Lucas Hnath’s The Thin Place at Playwrights Horizons as a successfully scary piece of in-person theatre.

Of course, horror theatre exists, as much as you can claim the existence of a genre so subjective in definition. In early 20th-century Paris, the Theatre of the Grand Guignol ran a solid business in early splatter horror. The Woman in Black has been spooking London audiences since 1989. National Theatre of Scotland’s often harrowing stage adaptation of the vampire film Let the Right One In was striking in its rejection of typical horror genre aesthetics, its bright, minimal design a welcome departure from the maroon-velvet-draped, often Victorian world of stage horror.

Immersive theatre is a more successful form for horror—haunted houses are an ur-form of immersive theatre, after all, and spiritualists leading scam séances were early practitioners—but it relies heavily on environmental control and the ability to direct audience attention. Making work to be consumed in someone’s home, an environment to which you have very little access, is a different challenge altogether.

“All of our previous work has been for audiences in total darkness, where we would use sound to create these imagined environments and characters that the audience would navigate through,” said David Rosenberg (he/him), who, together with Glen Neath (he/him), is creative director of the London-based immersive theatrical outfit Darkfield. Rosenberg and Neath have been making work together for more than a decade, recently inside shipping containers where they had complete environmental control: They could control the space, the scent, the last thing the audience saw before the lights went out.

Not having that control was the key challenge in building Darkfield Radio, an audio offshoot of Darkfield that just launched its second season, called Knot, via the easy and intuitive Darkfield app.

“The first thing we thought might be interesting would be to play with rooms that most everybody has in their home,” Neath said. “That has been an advantage, actually, because now we’ve played around with people’s familiar spaces, and also the people who are in their spaces with them, their partners or flatmates.”

Season 1 consisted of three short-form theatre pieces designed to be experienced in a row, in a kitchen, a front room, and a bedroom. Two of the pieces were experienced with a partner—an important step in helping the show feel live—but for Eternal, the piece set in your bedroom, you go it alone. By identifying items that would likely be common to these environments, they felt confident they could access a new kind of intimacy with their audience.

“These are all considerations we had in trying to create this doubt with the audience’s mind about what’s real and what’s imagined,” Rosenberg said. And what’s scarier than being unsure you can trust your own eyes, your own mind?

All Darkfield Radio shows are set at specific times of day and ask you to engage in specific ways—certainly your emotional response to your own pillow will feel very different than to any set design, which helps. So does the sense of appointment and task orientation; you can’t, say, do the dishes while you’re listening.

Though it feels uniquely suited to COVID-era theatre, these audio experiences were brewing long before our current reality. Darkfield has long capitalized on head-spinning technology, including binaural audio, a recording method which uses multiple microphones to create a sort of 3D soundscape, which feels like what you’re hearing is in the room with you. I wore an eyeshade during Eternal to try and keep myself from peeking, but after someone whooshed up close to my left ear, right next to me in my bed, I couldn’t help myself.

To create Season 2, Neath and Rosenberg again began crafting the three-part story around familiar spaces: a park bench, a car, the largest room in your home. Though less overtly eerie than Season 1, Knot shows Rosenberg and Neath’s propensity toward non-linear narratives that are unnerving: The words “unsettling” and “Lynchian” pop up semi-regularly in appraisals of their work.

“We don’t have a play and then think, how are we going to stage this?” Neath said. “Everything is made in relation to this idea of the audience, and how they’re going to be in the middle of it as the protagonist, in some way.”

Interestingly, letting go of environmental control can also help keep this kind of live theatre feeling live, and lend it the frisson of unpredictability often touted as unique to live, in-person performance. At a pivotal moment during one performance of Someone Else’s House, Mezzocchi said, a minor earthquake in California shook the laptops of some three-fourths of the audience members—and those on the East Coast thought it was a visual effect.

Theatres have long lamented the uphill battle of competing for audience attention with streaming television. It’s hard to entice people out of their homes. But what if you can entice them within their homes? At-home theatre is not by definition less compelling than in-person theatre, and we shouldn’t underestimate the human desire to connect, or the power of a sense of occasion.

“By doing things in people’s homes, we’re trying to create an audience for a new kind of entertainment,” Rosenberg said. Darkfield Radio is being consumed by audiences all over the world. Many of Mezzocchi’s audiences indicate that they’ve never been to the theatre before, he said. Perhaps horror’s unique ability to grip an audience, even from afar, can help ensure that remote theatre, and all the unique creative possibilities therein, will have legs well beyond shutdown.

There may be something even more fundamental going on as well. Said Mezzocchi, “There have been nights where people will not leave until they get confirmation that I’m okay. No one would do that in a theatre if they saw me run offstage in the blackout. But here there’s a genuine concern, and that’s specific to the online platform, and that’s exciting.”

Gemma Wilson (she/her) is a contributing editor to American Theatre.