This article is one of two we’re publishing today on anti-racism efforts within university theatre training programs. The other piece, about the efforts of student activists to hold these programs accountable, is here.

Over the past year, amid a society-wide movement for greater equity and accountability, academic institutions were not exempt from scrutiny. Specifically, theatre training programs were met with demands from students and alumni for great equity, transparency, and commitment to anti-racist practices. What has this meant for the many educators of color already employed in such programs? Many have felt caught between institutions, busy issuing statements of support while looking to quickly hire additional educators of color, and students who are leading demands for fundamental change at historically white institutions. Lisa Portes (she/her), head of directing for the Theatre School at DePaul University, put the challenge of the moment to me this way: “What do we need to do to support all of the Black, Indigenous, Asian American, Pacific Islander, Latinx, and MENA faculty that are being recruited like crazy across the country right now?”

It’s a sort of Pokémon effect, to borrow a turn of phrase from Madeline Sayet (she/her), with institutions scrambling to catch “one of each kind.” The result has been an over-emphasis on making sure that certain demographic groups are represented, minus the important consideration of how those new hires will be supported within these institutions over the long haul.

Portes recalled entering academia without such support. Though she said her dean at the time was always supportive, she also noted that there was an expectation among faculty to conform to systems and protocols already in place. In essence, she said, the vibe was “suck it up and deal with it.” But the conversation around diversity has begun to change over the last five or so years, Portes added, as more people discuss what it takes to institute and sustain true diversity, and what it means to be a truly equitable, diverse, inclusive, and anti-racist institution.

Still, many educators of color find themselves entering or working at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) with little guidance on how to push for change and support their students, while managing to take care of themselves. And there are still cases in which an institution makes a new hire as a Band-Aid solution when they’re called out for problematic practices, as if one person from a marginalized community can somehow suddenly solve the institution’s problems. The reality, Sayet said, is that such hasty action is only “going to traumatize that one person. If you enter an institution alone, you’re basically entering into a toxic environment and you don’t have any allies.”

By contrast, she recalled joining the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University as part of an all-educators-of-color “cluster” hire. “What that signals to me is that I’m entering into a space in which conversations about race will be a part of the conversations that the center is having,” Sayet said, “as opposed to, if I was being hired alone, there ends up being more of a situation in which you’re being asked to assimilate into an existing culture.”

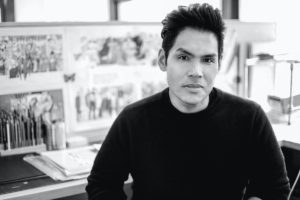

As many noted in my conversations for this article, improvements in theatre training must include upgrades of that underlying culture. Director Victor Malana Maog (he/him), a visiting professor of theatre and performance studies at St. Mary’s College of California, noted that there can be a historical default in many institutions when it comes to directors and professors—a default that says that those positions aren’t occupied by people who look like him. So there’s a degree of power and control in the room that would automatically be given to a white colleague that isn’t necessarily afforded to him. It’s not always as bad as the time he walked into a building and was pointed toward a janitor’s meeting, but that’s a signal example.

“There’s a huge amount of tokenization in that space,” said Maog, “where someone could hire someone like me and go, ‘Oh, you should really watch a director of color work,’ as though I were some sort of animal in a zoo. Even though I could understand all the techniques, whether it’s Stanislavski or whatever, I suddenly become this object to watch and observe. I suddenly become this, ‘Watch how this one works—watch how this Filipino director works.’”

“Folks of color in particular are vulnerable to isolation, and academia thrives on that kind of isolating. It serves folks in power, and it deprives folks of power who experience that vulnerability.”

Addressing these problems for artists of color within the academic sphere must begin with naming these transgressions. But it’s also important to look at who is in leadership at these institutions and talk about the positional power that comes with long-term employment. Some of the nation’s theatre departments may go decades without seeing a person of color in a leadership role. More starkly, institutions may go decades without having a single educator from some cultural backgrounds working anywhere there. If institutions are relying entirely on visiting or guest artists to supply their diversity, that affects the institution’s pedagogy. Without a full-time hand on the wheel, many marginalized communities wind up without a say in pedagogical choices that go on to become cornerstones of a PWI’s work.

“The folks with the security are, most of the time, not faculty or artists of color,” said Maog. “The numbers show who has security and positional power, and that needs to shift.”

Sophia Skiles (she/her) is stepping into one such position of power, allowing her a hand on the decision-making wheel as the incoming head of acting for Brown University/Trinity Rep’s MFA program. Though she agreed that the new hires that have been happening in recent years aren’t magical solutions, she does see them as powerful steps in the right direction. She also pointed out that there’s some potential “peril” for artists of color stepping into public leadership positions: In addition to the exposure and scrutiny that comes with these positions, there can be resistance from white leaders within these institutions, who feel threatened by any potential changes, which puts these new leaders of color in particularly vulnerable positions.

“Folks of color in particular are vulnerable to isolation, and academia thrives on that kind of isolating,” said Skiles. “It serves folks in power, and it deprives of power the folks who experience that vulnerability.”

After all, if you feel isolated, without allies or support, it becomes that much more difficult to question the status quo. This is especially true if your energy is spent correcting the mistaken expectation that you must represent your entire community, as if any educator of color could possibly stand in for a monolithic identity. At ASU, Sayet noted with relief that she is just one of dozens of Native professors, meaning that “there can actually be a discourse of ideas among Native scholars, as opposed to a situation in which you were representing Native people.

“What that means in an academic institution is very different,” Sayet continued, “because if you’re actually supposed to be in a space that is a hub of innovation and ideation, and you’re stuck in a situation where you’re defending and representing 24/7, you can’t actually do innovative, creative work, because you’re constantly in a fight.”

Sayet recalled her time as a graduate student, when she was often the only Native person in certain social situations. She found that much of what she would get a chance to say consisted of explaining, or re-explaining, herself just to get basic points across. This constant fight restricts the conversations artists are able to have, and prevents them from being able to actually do the exciting work that can truly push the field forward.

This feeling certainly extends to students, who may find themselves in PWIs without educators of color to whom they don’t feel they have to explain or defend themselves. Again, attempted quick-fix hires that simply add one person to cover a certain demographic are far from enough. In fact, these moves often put undue pressure on these instructors, who are now charged with supporting young theatremakers without additional support of their own.

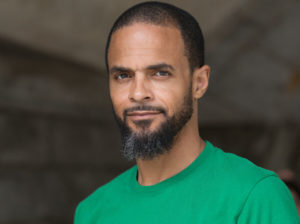

“We have to understand that hiring is not enough,” said Danyon Davis (he/him), director of American Conservatory Theater’s MFA program and head of movement. “One of the things we encounter a lot is that people have been scarred. People have been traumatized. People have been marginalized. People have been really harmed by these institutions, and it takes a lot for people to reenter those spaces and participate in change.”

Even with new personnel or leadership, he continued, it’s important for institutions to acknowledge past transgressions. New leaders must demonstrate that they can be trusted where their predecessors could not. These steps are crucial to institutions moving forward and finding healing within their communities, and they open the door for the possibility of true institutional change. As Sayet put it to me, shouldn’t the goal of education be to create a situation where people have the room to ask deep questions, learn from each other, and grow, rather than to indoctrinate students into preexisting systems?

“If it’s a space for transformational change,” Sayet said, “you need to create the terms for that transformational change to occur.”

Throughout her career, Sayet has found that academic institutions, even moreso than theatre producing institutions, are dominated by whiteness and white culture—a direct result of holding onto ideas and systems that came before rather than actively questioning them. Portes echoed this sentiment, noting that academic institutions are “rife with systems that uphold white supremacy,” with the tenure process being a central one.

“There’s no denying that these training programs exist in institutions, and there are frames and structures embedded inside of these environments that make it difficult,” added Brown/Trinity’s Skiles. “Why stay so long? What is actually the value of staying so long?”

Even Skiles admitted to struggling with the idea that her position could be a de facto “lifetime” appointment. One of the lessons she’s learned amid the changing theatrical and academic landscape, she said, has been that there are people who legitimately feel untouchable. This extends beyond simple job security to a feeling of exemption from continuing to learn and grow. The result is an unhealthy sense of authority, and a culture that is at best reactive to harm rather than proactively anti-racist.

“I wonder if the way to respond to institutional inertia, or institutional authority and institutional powers, is creating relationships,” said Skiles. “Without relationships, there can’t really be accountability that so many of these letters are calling for—a relationship where all folks are learning from each other, and all folks are changed by each other. And that’s a different model than the banking model of, ‘Here, I’m going to drop in my knowledge.’”

That stagnation may also be the result of requiring long-term professors to have Ph.D.s or terminal degrees, thus prioritizing academics over active practitioners. In terms of Native theatre, Sayet noted, many Indigenous knowledge keepers and culture bearers aren’t people with Ph.D.s, but their depth of knowledge and wisdom goes far beyond that restrictive qualification.

“It’s going toward a good direction, but it’s been exhausting. A lot of that labor, even prior to this sort of reckoning, really falls on the faculty of color, both formally and informally.”

Changing these kinds of ingrained institutional systems is difficult, and DePaul’s Portes called the tenure process a “sticky” one for faculty members of color. Artists of color in this realm, whether they’re visitors or full-time faculty, are evaluated over the course of years by a predominantly white group of colleagues and students, which means that bias can run rampant throughout that process.

It’s entirely possible for a fantastic artist of color, with credits through the roof, to receive middling evaluations from a predominantly white group of students. Or for an educator with enthusiastic evaluations from students to get docked by a tenure committee because their access to creative and research opportunities has been limited. Addressing biases inherent in this system is crucial to turning predominantly white institutions into what Portes called “historically white institutions.” This is why she recommends that everyone participating on a retention or tenure committee should take implicit bias training.

“It seems obvious,” said Portes, who serves on one such committee, “but it’s actually real. As committee members, we must evaluate not only our own implicit bias, but how colleagues are evaluating faculty members of color and how students are evaluating faculty members of color.”

When Davis moved into his position of power at ACT, following conservatory director Melissa Smith’s departure at the end of 2020, he said he had to take time to truly examine his relationship to white supremacy, evaluating what unconscious biases he might have. At St. Mary’s, Maog said, they are working to make faculty meetings more transparent, publishing notes from meetings as well as thoughts around curriculum and programmatic changes. This move both opens up some of the typically hidden processes within academia, but also gives faculty an opportunity to provide continual clarifications on the program’s aims, as well as students a chance to see inside.

This effort is similar to one at DePaul to adjust the season selection and casting processes to be more transparent. When looking at her institution, Portes pointed out that seasons have traditionally been decided by a group of around five people, and for a while she was the only woman and the only person of color in that cohort. After student outcry following the death of George Floyd, and a mandate from the program’s alumni, who spoke out about the harm they had experienced, the dean, John Culbert, and others in charge began the process of examining a number of systems that had caused harm, including the season selection process.

Now seasons are decided by a committee of 14 people, including students, faculty, and staff, to create a season that Portes said is much more representative of the theatre school’s student body and community than before. Having students in the room as part of these conversations has allowed shows to be more representative of their needs and interests.

“One thing that I’ve learned this year is: Ask students about everything,” said Portes. “We have brought students into just about every single conversation. And before we’ve made any decisions this year, we’ve tended to poll the students. The students know more about what’s happening on the ground in their world.”

Hand in hand with season selection is casting, which Portes said is “riddled with potential for harm, and it always has been.” It’s tricky for programs like DePaul, which have guaranteed casting, and can see upwards of 70 students cast in roles twice a year. In theory, the previous system had been a thoughtful one, placing students in roles based on faculty evaluations on what would be good for them and their growth. But it also was a system with potential for harm when it failed to take into account how student actors may or may not be able to bring their full identities to their roles. In a change this year, Portes said that, after announcing the school’s upcoming season, they asked actors what plays and roles they were most interested in and what roles they were not.

“Previously, our priorities had been the needs of the play and the training of the students from the faculty perspective,” said Portes. “Now we had the actors’ voices in the room. I think we just came through our most successful casting round ever, where we feel confident that our student actors will be excited about the roles that they’re in, will grow from the roles that they’re in, and be fully on board the productions they are a part of.”

To that latter point, Portes noted that professionally, actors typically have a choice whether or not they’d like to audition for or accept a role, whereas a conservatory program with guaranteed casting doesn’t afford that flexibility. Of course, these changes have meant dedicating extra time to the process; DePaul also added associate diversity officer Azar Kazemi to the casting process. Kazemi was able to sit in and ask questions—like, for instance, what it would mean to cast a Black actor in a role that involved violence or trauma in the immediate wake of George Floyd’s death—which deepened the conversations in the room.

“Across the board, it’s about embracing the student voice, embracing student agency,” said Portes. “That’s the first way you actually start to take down harmful systems.”

The most common mantra throughout the conversations I had for this article was this idea that students should be allowed to be more involved and that institutions need to open up to the possibility of learning from students. Too often academic institutions become insulated bubbles, teaching a certain history or process of theatre without fully taking into account the innovation and change taking place throughout the rest of the field. The conversations happening around anti-racism and equity in the field must also happen in the classroom.

“As a student,” Skiles said, “I was always hungry for the classroom to hold conversations that were happening outside. I wanted it to be more porous. I wanted the art to matter. I wanted it to feel relevant. I do think if you’re not addressing it in some way, there’s an act of denial happening.”

This kind of isolation from the larger world, whether intentional or not, can result in much of academic practice being geared toward comparison and critique. What exactly, Sayet wonders, are we training theatremakers to do? She noted the propensity for theatre education programs to dictate a “right” way to breathe or speak—a tendency that almost led her to quit theatre multiple times when, she said, “Suddenly I felt like everything was wrong with me.”

“I couldn’t breathe correctly, I couldn’t speak correctly,” continued Sayet. “Nothing I did was right, probably because I’m not meant to be in a Pinter play. Not because there’s something wrong with me, but because the world in which I was supposed to exist was under certain terms at the moment.”

This intuition led her to her current path: directing. She didn’t want to have to exist within the confines of someone else’s world, so she set out to reimagine and forge a new one.

“That’s the thing that is scratching at the back of my head,” Sayet said, “the difference between, how do we teach them what we think is good, versus how do we empower them to imagine beyond what we know? I feel like whenever I talk to young people, it’s like they’re always going to be ahead of us. That’s the very nature of intergenerational change: The young people will always know things we cannot know. So how do we actually facilitate that, as opposed to trying to fit them into a mold that will always be a generation behind?”

As an example, she pointed to a Shakespeare survey course she taught at the Old Globe in San Diego, where she challenged MFA students to grapple seriously with the question: Why produce this play now? She recalled one moment in a discussion of Othello when many Black actors present expressed the feeling that they didn’t want to do the production at all unless there were other Black actors involved. This allowed them the space and time to have conversations around the work’s impact before they found themselves in a situation of potential harm.

Of course, making room for these conversations can sometimes call for curricular changes—a process many said can take multiple years, especially in programs where much of a student’s slate is predetermined. Still, it’s important to work to expand the conversations happening, creating space for innovation and new ideas—without, as Sayet pointed out, limiting those conversations based on what academic writing and thinking already exists, and what conversations previous gatekeepers have deemed worthy.

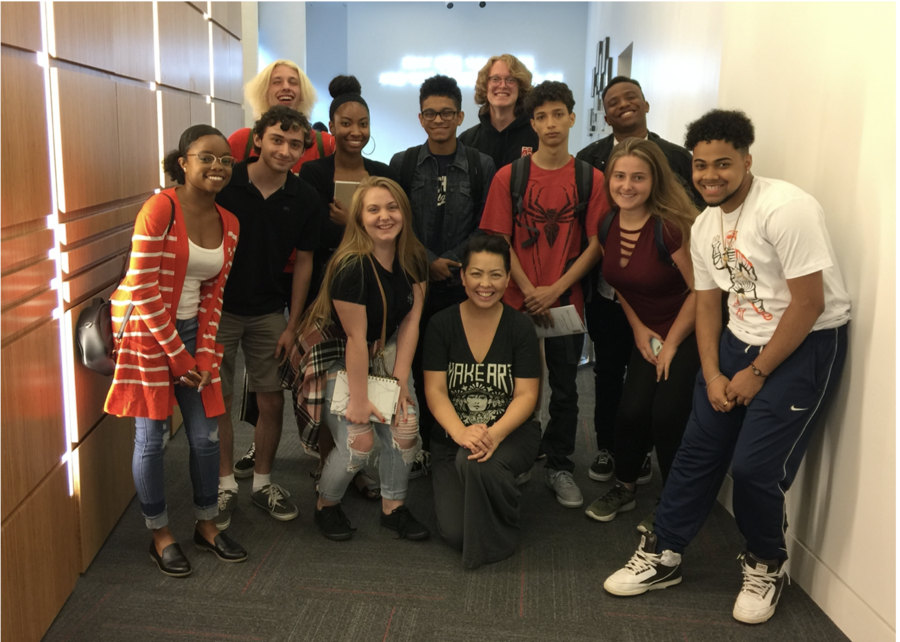

At Fordham University, head of design and production Clint Ramos (he/him) said that their program is in the midst of a curricular overhaul as the school shifts toward a social justice program. These efforts have happened alongside students of color organizing a document detailing what they want from the program, and support from the university itself in the form of mandatory trainings and workshops through ArtEquity.

“It’s going toward a good direction,” said Ramos, “but it’s been exhausting. A lot of that labor, even prior to this sort of reckoning, really falls on the faculty of color, both formally and informally.”

Indeed, faculty of color tend to be the first point of contact for students of color. So on top of their course load, faculty of color are also often tasked with meeting students on a personal level when they experience harm or are facing a difficult situation due to racism within the institution. It’s tough, since many educators instinctually extend, or perhaps overextend, themselves for the sake of educating. Many times that results in educators of color feeling the need to teach not only their students but their white colleagues as well. But as Ramos noted, this extra labor of pulling their white colleagues along isn’t in fact part of their job descriptions.

There’s a sentiment here shared by educators of color and student and alumni organizers alike: that in this push for more anti-racist educational institutions, the people of color are the ones caught in the middle and burdened with extra labor. Both groups are actively seeking to help and working for change, but that desire can quickly result in the floodgates opening, as those who have been harmed at least have folks who will listen. That healing work is so crucial, but there’s no avoiding the fact that the true weight of decades of institutional inertia and harm still falls on the shoulders of artists of color. It’s so important, as Ramos said to me in a reminder to his colleagues, for artists and leaders of color to find time to pause, breathe, and take care of themselves in the midst of painful institutional change.

“I feel like they need to actually, really look at themselves and check in with their spirits in a real manner,” said Ramos of his colleagues of color. “On a pragmatic level, please take into account all of the extra labor you’re doing that your white colleagues are not doing: all of the advising you’re doing, all of the hours on the phone that you’re spending with students, all of the triaging that you’re doing. And if that emotional labor and actual real physical labor is substantial, then ask for a course reduction, because it has to level out. Luckily, I think universities are slowly beginning to understand the immensity of this labor the faculty of color actually perform for the institutions.”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor of American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org