Producing is Candace Feldman’s passion. Being able to take a concept or idea and flesh it out so that it has the potential to make a positive impact on society is what made her accept the position of director of programming for the University of Arizona Presents (now Arizona Arts Live). Her job involved producing and programming the performing arts season, helping grow audiences, and supporting fundraising efforts. Feldman (she/her) says that she was enthusiastic about bringing world-class acts to the university and infusing more diversity in the programming.

But what she thought was a dream job quickly turned into a nightmare. Colleagues made dismissive comments about her interest in diversity, asking, “Does it always have to be a Black thing with Candace?” She says that during meetings, the dean at the time would roll up his agenda and literally pat her on the head with it. Further, her initial salary offer was $50,000—a full $35,000 less than her predecessors.

In 2018, things came to a boiling point and Feldman resigned. Her resignation was leaked to the press, and so were her plans to file a federal lawsuit against the University of Arizona, citing a culture of racism, discrimination and inequitable compensation. Unfortunately, her lawyers dropped her as a client and she was unable to find a viable alternative by the filing deadline, so the case went away.

“I wasn’t respected,” Feldman says. “I had a title, but I didn’t have authority, voice, or power. I’ve been in therapy for three years to clean my soul of that experience.”

Feldman turned her encounters of discrimination, systemic racism, and inequity at the University of Arizona into a what she calls “proactive activist business.” She and Ashley Walden Davis founded Unlock Creative Coaching & Management Solutions, a social enterprise whose mission is to nurture, grow, and sustain Black creative leadership, with a priority on Black women.

“The field is going to be what it’s going to be because of who is in power,” Feldman says. Her and Davis’s aim will be “to show what it is to be just, equitable, and right,” though she adds, “Accountability is coming regardless. It’s up to the field to change. It is not up to me to change the field.”

Feldman’s experience is hardly an outlier for Black women working in the theatre. As the impact of racism and sexism is compounding, Black women regularly experience distrust, micromanagement, emotional abuse, microaggressions, and gaslighting as well as condescension, sexual harassment, and unequal pay. But instead of staying in those abusive environments and trying to change them from within, many have opted to start their own businesses with the aim of giving other Black artists and administrators opportunities and equipping them for the work.

Erin Washington (she/her) started the SoulCenter, also in Atlanta, after working at a number of renowned regional theatres, including Arena Stage, Penumbra Theater, and Oregon Shakespeare Festival. SoulCenter was born out of her previous company, Soul Productions, which she started in 2010 after completing her MFA program and seeing the need to create art that centered independent Black artists in theatre, film, and music.

At SoulCenter, she is the lead “waymaker” for Black creative-led arts initiatives, ranging from producing and writing groups to design work and content development. She works alongside a group of four other Black creatives, including her associate waymaker, Toran X. Moore, fellowship coordinator Dara Prentiss, and creative producer/anthropologist Shanya Cordis. The space is funded by community members, value-aligned grant organizations, and content development projects. No idea is too big or too small for SoulCenter—an ethos she is determined to bring to that space after hitting walls with her ideas at regional theatres.

“Black women’s ideas, Black queer women’s ideas, are big, and often they feel outside of the budget line of possibility, because we’re long-term thinkers,” Washington says. “When we make something, we’re thinking about lineage. The American theatre is often a very reactive space, but the Black women I know are innovators and activators.”

Washington’s last gig before going full-time with SoulCenter was as interim associate artistic director at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, where she had earned her MFA a few years earlier. She worked on the Women’s Leadership Conference and created the popular Bayview Arts Festival. Though she is proud of the work she was able to do there, the achievements weren’t without obstacles. There were challenges to her authority from the start. She says that the environment at the theatre fostered a space where Black women’s ideas were second-guessed and white patriarchy was centered.

“People have an issue with Black women having the audacity to say, ‘This is what I do and this is what I don’t,’” Washington said. “I literally had to train people on how to listen to me. That should be present before I arrive.”

In the next five years, Washington plans to open a SoulCenter in her hometown of Montgomery, Ala., as a cultural arts space for children and their parents to create art. The goal is to have centers across the South. She wants to pass these spaces on to other Black creatives, as a way of fostering intergenerational dialogue and legacies within the community.

The issue of Black women feeling unwelcome in leadership roles is related to Black women’s unique history in the American labor force, which for the first 500 years required them to be silent and tend exclusively to the needs of white people. Many Black women’s ancestral lineage has a history in chattel slavery. After Emancipation, Black women were forced to continue agriculture or domestic work. The most common profession for Black women from the 1880s to the 1940s was laundress. For the next 30 years it was maid.

Unlike white women, Black women have always worked and often been the primary breadwinners for their households. The subjugation and disproportionate incarceration of Black men made this a necessary burden to feed their families.

This means that for most of their history in the U.S., Black women worked without employer-provided retirement plans, health insurance, paid sick or maternity leave, or paid vacations. Even today, 36 percent of Black women do not have paid sick leave. Further, in the private sector, the professions most likely to hire Black women are nursing, social assistance, and nonprofits. These are all honorable and essential professions, but they still involve catering to other people’s needs.

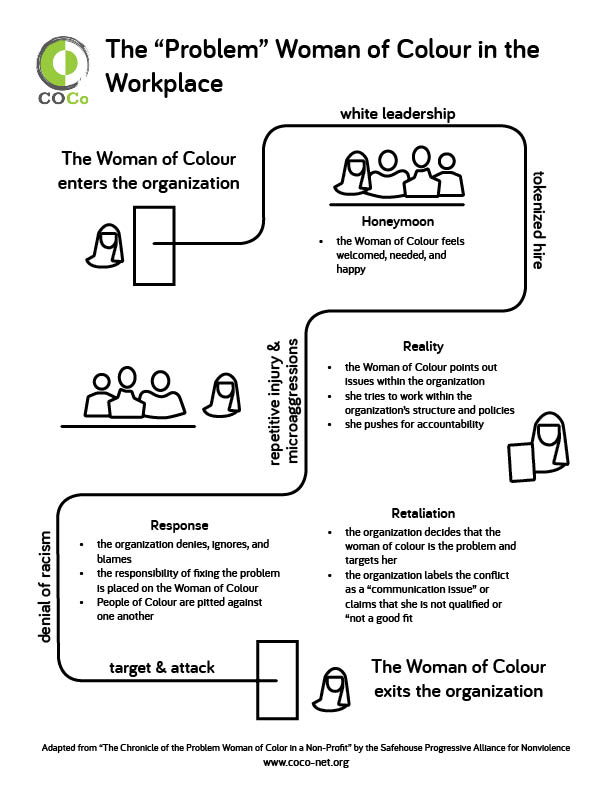

Since most people’s experience of Black women in the workforce is rooted in submission, when they do move into management or leadership positions, it can be disorienting for some people. Their creative ideas and labor are desired, but allowing them to set boundaries and direct the execution of those ideas becomes a source of conflict. The Centre for Community Organizations in Québec created a chart that illustrates this idea. It’s as if the maid became the mistress of the estate—a plantation mentality still haunts the labor market.

“We have the opportunity to shift our lens of Black creativity and how Black artists participate in majority white spaces,” Washington says. “We have the opportunity to shift our relationality. We [as Black women] don’t have to just be the needed—the savior. We can be the innovator.”

Moving more diverse people into leadership positions in the American theatre is what inspired Jocelyn Prince (she/her) and business partner Al Heartley to start ALJP Consulting Group. Currently, Nataki Garrett at Oregon Shakes and Hana Sharif at St. Louis Rep are the only Black women serving as artistic directors of major LORT theatres, which remain predominantly under the leadership of white men.

Prince could hardly speak through tears as she recounted the many instances of discrimination and harassment she experienced in the nonprofit theatre field.

As an intern at Steppenwolf, she says people always confused her and another Black intern for each other. At the Public Theater, there was a culture of “no mistakes,” and a colleague told her that she needed to make her personality more like that of a white male co-worker. At Woolly Mammoth, during a meeting she told a superior that she was being racially discriminated against by other colleagues, and the person laughed at her.

Perhaps the most lasting was when Prince was working in the education department at Cleveland Play House, and she reported sexual harassment by a Cleveland Metropolitan School District employee to the Play House and the school. According to an investigation by the school district, the school retaliated against Prince for reporting the harassment by recommending her removal. CPH put Prince on a leave of absence within weeks, never returned her to work, and later entered into a settlement agreement with her. Due to the agreement’s confidentiality, Prince could not comment on its terms.

Prince now uses those experiences as fuel to make sure that no other people of color endure the same harms that she did at work. At ALJP, she and Heartley consult with arts organizations on searches from start to finish. This includes everything from helping them write job descriptions in an equitable way to facilitating salary negotiation. Some companies retain them to help support candidates of color even after they are hired.

“We’re about representation and reducing harm that BIPOC people experience during the recruitment, interviewing and onboarding process,” Prince says.

While Prince and others are working as consultants to help change the field’s practices, like Washington, Lauren E. Turner (she/her) is more concerned with an exit strategy. She is building an alternative model outside white-dominated theatres. In 2016, she started No Dream Deferred in New Orleans with a friend and colleague, India Mack. The goal of their organization is to be an arts incubator for Black artists in New Orleans, with a focus on developing new work by local playwrights of color.

She worked as a community engagement manager at a major theatre in New Orleans from 2016 to 2018, making her the organization’s first Black employee. She was hired through the TCG Leadership U Grant, which provided a salary and matched her with a mentor. In her application, she stated that she wanted to embed herself at a major theatre and create a slate of community engagement programs as a testing ground for eventually starting a theatre in New Orleans for people of color. But she says it quickly became clear to her that she was viewed as a token.

Turner says that the first sign came when she was asked to accompany the leadership team on a site visit to a new space located in a majority Black neighborhood. The theatre had a reputation for being exclusionary, and Turner says it didn’t take her long to realize that they brought her along to show the Black community that they were changing, even though Turner says she knew they weren’t.

As she continued her duties, community members started asking for her to appear at meetings and speak to build trust between the theatre and the people. These outside activities, she says, were met with suspicion by the artistic director. The theatre created a handbook for the first time, in which one section stated that any compensated speaking or outside engagements needed to be approved by the artistic director.

“I went from pet to threat,” Turner says. “I had to verify where I was to the artistic director at all times in a way that other staff members did not. She said that she felt ‘proprietary’ over me…This idea that we’re untrustworthy with labor and money is rooted in plantation culture.”

After leaving New Orleans, Turner went to a presenting company in Brooklyn as the executive director and faced many of the same obstacles.

As a mother and artist, she sees investing in No Dream Deferred as a move toward freedom. For the last four years, she and “the dream team” have worked to secure funding for the organization, but hit the same obstacles Turner faced in the nonprofit theatre: People didn’t take them seriously, and major funders doubted their ability to be good stewards of large gifts. This led them to start Equity and Justice for Institutional Change, a service within No Dream Deferred by which they help organizations move toward equity. Turner believes that not solely relying on foundation and corporate support has allowed them to be more ethical in their practices, such as operating with a collective leadership model.

“From an administrative point of view, our values show up in the how and in the budgeting of what we do,” Turner says. “We are pushing transparent budgeting. We have a queer youth theatre in New Orleans called LOUD, and they have a line item in all of our budgets. Our intention to be good community partners is stated in our moral document, which is our budget.”

Looking forward, Turner and the team plan to cultivate global majority playwrights in New Orleans and create a festival that celebrates that work.

“We [as people of color] have to stop thinking of the prize as clawing our way in and climbing this mountain,” Turner says. “There is no correct posturing or enough respectability that we can offer up to cure white supremacy culture when it’s rooted in the dehumanization of us.”

Kelundra Smith (she/her) is a contributing editor to American Theatre magazine. kelundra.com