Among the many well-documented and amply worried-over scourges ushered by in our interconnected technological age, this is also a time when crowdsourced information sharing has never been easier or more accessible. So when, for instance, a female journalist inspired by the #MeToo movement wanted to share information about men in her profession who’d been accused by other women of harassment and worse, she created the Shitty Media Men Google spreadsheet. When Signature Theatre’s resident dramaturg Jenna Clark Embrey wanted to create more transparency about unequal compensation in theatre jobs, she created an anonymous spreadsheet of salaries in the field where fellow workers could compare notes. And when, last summer, theatre producer Marie Cisco watched the the virtue-signaling spectacle of many theatres making Black Lives Matter statements, she created a spreadsheet to track their words and actions.

Public spreadsheets like this can be used not only by individuals to hold institutions accountable. They can also work in the other direction, providing institutions with the tools to do better in the first place. Many of the nation’s predominantly white theatres have long claimed to want to meaningfully diversify their hiring, and in the past year have felt redoubled pressure from the demands of We See You White American Theater and related movements. Giving theatres no excuse to rely on their familiar Rolodex was director Megan Sandberg-Zakian’s famous and widely used BIPOC Theater Designers and Technicians database, which she started in 2015 so that theatres and productions looking for designers of color had a one-stop shop to seek them out.

Last summer her colleague Kareem Fahmy, a director and playwright, was using the downtime of the COVID shutdown—and the support of Theatre Communications Group’s Rising Leaders of Color program—to make calls and take Zoom meetings with artistic directors around the country. He started to hear a common refrain, and saw an opportunity for leadership.

He was talking to Karen Azenberg, the artistic director of Pioneer Theatre in Salt Lake City, where he’d directed a workshop and one of his plays is in development. Azenberg, he noted, is not new to the business or unconnected—she used to be the board chair of the Stage Directors & Choreographers Society. “Karen knows what’s up,” as Fahmy put it. But in trying to create more opportunities for directors of color at her “white white white” theatre in Utah, she confessed to him that she had to rely mostly on word of mouth and occasional visits to New York to scout talent. “What I personally need is a list,” Fahmy recalled Azenberg telling him.

In a subsequent conversation with Denver Center Theatre artistic director Chris Coleman, Fahmy was told that the Denver Center staff was “actually going through Megan’s list and identifying promising designers so they could arm themselves with more connections to designers with diverse backgrounds.” He realized, as he put it, that “lists are helpful, because artistic directors and their staffs are very busy. They’re very siloed in their communities. And they don’t know whose work they should be tracking.”

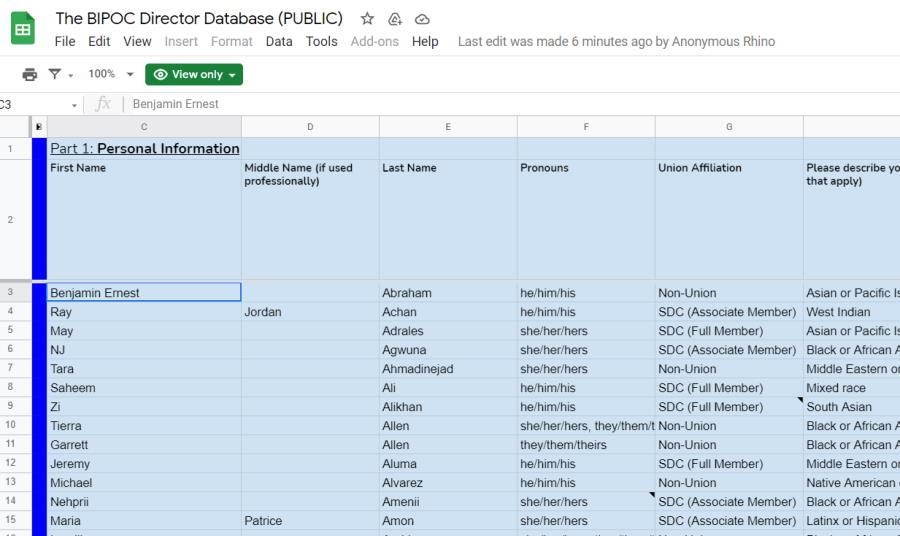

Thus was born Fahmy’s new BIPOC Director Database, which thus far contains the names and details for 227 directors who are Black, Indigenous, or people of color. To create it, Fahmy surveyed not only artistic directors about what they would like to know about prospective hires, but also his directing colleagues about what information they would be willing to share. The result is a comprehensive spreadsheet with three sections: one for personal information (name, gender pronouns, background, union affiliation, and location), one for contact information (including agents where applicable), and one for career experience, which has fields for degrees, honors, specialties and interests, and years in the business.

“Ideally, it can be many things to many people,” said Fahmy. “So if an artistic director is like, ‘I want to search this database to identify a BIPOC director based in the Bay Area and who has at least five years of experience and is an SDC member,’ it can be that granular. Or it could just be, ‘I want to know who the Latinx directors are,’ or, ‘I want to know who the Indigenous directors are.’ It is searchable through a lot of those parameters.”

Among the challenges faced by U.S. theatre directors, both practitioners of color and their white counterparts, is the feeding frenzy that can happen when an in-demand director becomes a hot commodity. Directors who toil in obscurity for years can suddenly get a high-profile regional, Off-Broadway, or Broadway gig, and then everyone wants to hire them, whether it’s Sam Gold or Lileana Blain-Cruz. Fahmy said the BIPOC Directors Database could also be used by fellow directors who want to be able to refer directors to qualified colleagues when they can’t take the gig.

Another fact of theatre hiring is that for every director tapped by an artistic director to helm an existing project—or even bring a wish-list show into a theatre’s season—is a director who comes as part of a “package” when the theatre books a given playwright. As a playwright himself, Fahmy said he sees uses for the database as well.

“It happens a lot in the Middle Eastern theatre community, which is really my world—sometimes a playwright wants to say, ‘I really need somebody who has a very specific shared cultural identity for this project.’ And sometimes they want exactly the opposite of that. Again, I want to make it easy for anybody to access that information. If somebody is saying, ‘You know what, I really want to be working with an Asian American female director on this specific project,’ it’s not that easy to find that information.”

Directors are often inclined to bring networks with them, which means that hiring them can have a multiplier effect for theatres.

“I’ve started to see it happen already, where the director of color tends to be the one who can then bring along designers, dramaturgs, cultural consultants or color,” said Fahmy. “People are seeing that this can be a way to bring in a lot of new blood to their institution, whereas a playwright may only bring the play and a director.”

The only tough choice Fahmy faced in the creation of the database, he said, was in setting a minimum bar for entry.

“It’s for people who identify as professional directors who are currently working in or aspire to work in the professional theatre,” he said. “This is not a database for people who are dabbling in directing. I’m a hyphenated artist myself, but this list is not for folks who are ‘interested in’ directing who have never directed.” So a caveat on the open Google form reads, “You will be asked to verify your commitment to theatre DIRECTING as a professional career. If directing for the stage isn’t one of your PRIMARY artistic practices, please do not add yourself to this database.”

The maintenance of an open-source Google spreadsheet is unlikely to take up much of his time in the future, and good thing, because 2021 is already looking busy for Fahmy. He is a 2021 Yaddo resident writer, and upcoming readings of his work include American Fast at Capital Repertory Theatre in Albany, N.Y., on April 28, and A Distinct Society at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley on May 8. For a May 16 reading of the latter play with Chicago’s Northlight Theatre, Fahmy will be working both sides of his hyphenate, as both writer and director.

“I see this from both sides, as playwright and director, and playwrights have a lot of opportunities—so many places they can submit their scripts, so many major prizes and awards and fellowships,” said Fahmy. “Directors have way fewer avenues. Hopefully that is going to start to shift.”

The BIPOC Director Database can be found here, and the form to qualify for listing on it is here.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org