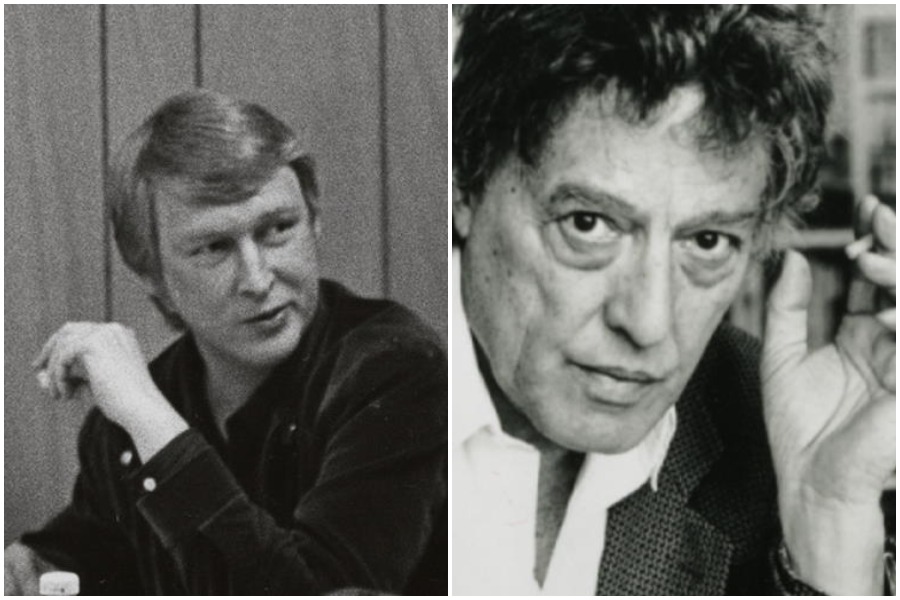

Two WW II refugees, both fleeing the Nazis and the privations of their childhood, employed new names and personal myths in the service of singular theatrical ambitions, and both are the subject of recent biographies.

One of them, 7-year old Igor Peschkowsky, by a stroke of “undeserved, life-shaming luck,” disembarked the S.S. Bremen one spring morning in 1939 with only his three-year-old brother in tow. Or at least that’s the tale Mike Nichols liked to tell about his origins.

Eighteen years later Igor, now known as Mike, was plying his trade in Chicago as an improv comedian with an artistic partner as witty and sardonic as he was. Arriving in New York with $40, Nichols and May in a matter of months leapt from late-night clubs to network television, a Town Hall appearance, a record deal, and $5,000 nightly fees. The next year their Broadway show was the hottest ticket in town. Mike Nichols’s “bitter good fortune” had begun.

The warp-speed advent of wealth and celebrity disoriented Nichols for the rest of his life. In a juicy biography based on 250 interviews, and combining canny theatrical analysis with tangy Hollywood legend, Mark Harris depicts Nichols as a deeply conflicted bon vivant and a compulsive director who caromed between success and failure, art and commerce.

Bald from an early age, Igor shape-shifted—toupee and all—into a seductive, acerbic wit with no trace of the Russian Jew from Berlin. During a constantly frenetic life, he would ask himself “what happens next,” as if having one eye over his shoulder to make sure the Nazis weren’t gaining on him. As a child he knew his mother was having affairs, and once in New York he and his brother were sent to live with two of his father’s medical patients. By his own admission Nichols spent much of his adult life trying to sort out his childhood.

Along with Elia Kazan, Nichols became that rare director who regularly moved between theatre and film in a career honored with eight Tony Awards, a Grammy, and an Oscar. Yet his most original work may have been the routines with Elaine May. They invented a cerebral, sexy, and satiric style of contemporary comedy, closely observed but with a healthy splash of absurdism. Robert Brustein described them as the “voice of outraged intelligence in a world given over to false piety, cloying sentiment, and institutionalized stupidity.”

“When I’m rich and famous…” was a constant Nichols refrain. His de facto lifestyle coach, the photographer Richard Avedon, introduced him to society, art history, and the world of conspicuous consumption. He hobnobbed with movie stars and presidents’ wives, feasted on beluga caviar, and collected Bentleys, Arabian horses, and paintings by modern masters. He owned multiple palatial residencies and spent considerable time holed up in luxury hotels.

Ultimately wealth wasn’t a very successful revenge. Nichols’s personal life boomeranged between elation and melancholy. Along the way he leapt into three marriages that failed, producing three children.

The restless Nichols entertained the dream of becoming a serious dramatic actor even during his partnership with May. After many years as a director, he would occasionally revisit that desire, most notably in a devastating performance in Wallace Shawn’s play The Designated Mourner. A summer stock job directing The World of Jules Feiffer led him to his true vocation. It was a logical step from there to helming Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park on Broadway. Nichols quickly recognized that a boy who was missing his late father throughout adolescence would be reassured by playing the role of a group father.

The routines with May taught him how a scene worked—excellent training, as it turned out, for a director. Nichols became known for guiding actors with minute physical detail. At the time, this was a novel approach to directing comedy on Broadway, and will probably serve as his legacy. Broadway acting typically featured mugging, smirking, and facing front. Influenced by acting classes he took with Lee Strasberg, Nichols demanded truthful behavior. Most actors loved working with a partner who knew the actor’s craft. For others, his unshakeable air of steadiness and certainty was unsettling; Alan Arkin once asked him: “Why are you so uninvolved in this experience?” But inside an urbane and debonair persona Nichols often felt like he was on the deck of the Titanic. In a career replete with contradiction, he was some actors’ favorite director, while often singling out a cast member for inexcusable abuse.

The relationship with Simon made Nichols the king of Broadway, with four hits running simultaneously in just over a year. That was how he summoned the chutzpah to call Elizabeth Taylor’s press agent to tell her he should direct the film of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Having been chaperoned briefly in Italy by Nichols during a stressful time, Taylor quickly agreed.

With no idea how a camera worked, Nichols prepared by watching A Place in the Sun dozens of times and conferring with industry pros like Tony Perkins, who taught him the basics of shooting. And in spite of the international soap opera that surrounded Burton and Taylor, Nichols spurred them to superior performances. He also made two bold decisions that contributed to the movie’s success: He hired the brilliant cinematographer Haskell Wexler and insisted the movie be shot in black and white. For this first film, Nichols received a Best Director Oscar nomination, and a year later he would take home the statue for The Graduate, after the gutsy choice of casting an unknown Dustin Hoffman. Barbara Walters crowed: “You are without a doubt this year’s No. 1 celebrity.”

Still, after winning the Oscar for The Graduate, Nichols warned: “Wait! You’re going to see such failures you won’t believe it.” He wasn’t wrong. Being the only director able to get Catch-22 greenlighted turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory. He made a bloated and aimless film that became a symbol of grandiosity and arrogance. It had the special misfortune of arriving at the same time as Robert Altman’s far more consequential war movie M*A*S*H, a film Nichols watched with envy and despair. When he tried to rebound by returning to the theatre, he chose a hapless musical, The Apple Tree. This time Brustein would take him to task for “becoming famous directing the kind of spineless comedies and boneless musicals that he once would have satirized.”

With more challenging plays like Uncle Vanya, The Little Foxes, The Country Girl, and Betrayal he often couldn’t find a way in. Directing Waiting for Godot for Lincoln Center he licensed Robin Williams and Steve Martin to speak directly to the audience to get bigger laughs. The approach made a hash of a play about isolated souls.

After The Graduate Nichols found himself trapped by big stars and small ideas. Most of his movies paled next to the New Hollywood of Scorsese, Altman, and De Palma. As Harris astutely observes, in the middle of Nichols’s career, “many of his professional decisions would derive from a combination of impulsivity and caution, recklessness and magical thinking.” But somehow when his career had reached a nadir, he manufactured a comeback. He returned to New York theatre with an explosive production of David Rabe’s powerful Streamers and followed with the success d’estime of Trevor Griffiths’s Comedians.

Depression shadowed most of Nichols’s adult life, and in 1986, with no shows on the boards and a third marriage at an end, he suffered a nervous breakdown, partly the result of cocaine and Halcion addictions. Paranoid about money, he sold off paintings and horses, begged a friend to lend him $25 million, and considered suicide. Friends insisted he check into a psych unit and the worst was averted. In Harris’s insightful observation, Nichols “reconsidered his life not as ongoing search for meaning in art but as a decades-long flight from himself.”

There would be a string of mediocre movies in the ’90s and an oversized Broadway production of Death and the Maiden that made him swear off Broadway for good. But it wouldn’t last. He rediscovered Hollywood box office success with The Birdcage and won an Emmy for an acclaimed production of Angels in America. And 48 years after his first Tony, he won his seventh for Death of A Salesman in 2012.

Whether it was fear of failure or an iron will, or both, somehow Mike Nichols defied Fitzgerald’s admonition that American artists have no second acts. He had a handful.

Tom Stoppard’s whirligig life began as Tomas Straüsler.

On March 15, 1938, the day the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, 18-month-old Tomas and his family escaped to Singapore, where his father, a British army volunteer, later died at sea. When Singapore was invaded, mother and children embarked for Australia, only to wind up in India, wandering from city to city, finally settling into a new family and country when his mother Marta (called Bobby) married a British soldier named Stoppard.

At the age of eight, in 1946, Tom’s charmed life began. He invented himself as a proper Englishman in Derbyshire, embracing his new country with zeal. Delighted to have “married into British democracy,” he eventually become an ardent Thatcherite and a friend of the royal family. Stoppard’s extraordinary journey is given a voluminous and sympathetic treatment by Hermione Lee in a book anchored by an intimate 50-year correspondence between Tom and Bobby.

Restless from an early age and eager to start making a living, Stoppard began working for newspapers in Bristol. Journalism suited the quick-witted teenager; he had “an ear for what was funny and an appetite for what was interesting.” Newspapers would be his university. He also had the good fortune to live in a city with a major theatre. All but taking up residence at the Bristol Old Vic, he watched Peter O’Toole in everything from Hamlet to Godot. He fell in love with the art form and the celebrity, telling his mother, “I’d like to be famous.”

Creating satirical columns under a pseudonym was a natural steppingstone to playwriting. BBC radio and television’s need for all manner of narrative content gave Stoppard’s aspirations a major boost. Broadcast work also led to acquiring a shrewd agent in Kenneth Ewing, who suggested he write a play centered on Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. With the RSC and the National Theatre competing fiercely in London, it was a serendipitous moment for a promising young playwright with a play based on Hamlet.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead allowed Stoppard to hone a comic voice. riff on Godot, and unleash a torrent of verbal gymnastics. London critics were over the moon, delighted to endorse a modern young playwright who, in contrast to most of his British contemporaries, wasn’t amplifying left-wing politics. In a few years “Rosguil” was translated into 20 languages and produced in 23 countries. While some considered the play an important philosophical statement, Stoppard insisted, “I didn’t know what the word ‘existential’ meant until it was applied to Rosencrantz.”

Until the middle of the ’70s Stoppard was largely an entertainer serving up plays dominated by brilliantly synthesized ideas and verbal razzle-dazzle. In the words of the director Charles Marowitz, Stoppard was “the theatre’s intellectual P.T. Barnum.” His friend and supporter Kenneth Tynan would say “he had withdrawn with style from the chaos.”

He’d also found a successful and lucrative technique which supported a family and a penchant for treats and luxuries. As a grateful Englishman, he had always been conservative. When Soviet forces invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, he was horrified but did not speak out. That changed when protestors in Moscow were sent to insane asylums. Stoppard began to feel “criminally insular and over-privileged,” and that “the truth was too serious for tricks.” It was one of the two major pivots in his career.

He traveled to Moscow and the Czech Republic, befriended the playwright, activist, and politician Vaclav Havel, as well as other dissidents, and later supported Soviet refuseniks and the Belarus Free Theatre. He grew determined to make the suppression of the individual in Eastern Europe a personal cause and a key writing motif.

The immediate result was the brilliant Every Good Boy Does Favour (1977), a collaboration between the RSC and the London Symphony Orchestra, with music by Andre Previn. EGBDF focuses on two men named Ivanov: one a dissident confined to a mental hospital who will be released only when he admits that his protests are the result of mental illness, and the other an actual schizophrenic conducting an imaginary orchestra. In the Soviet system, the two were indistinguishable. With devastating satire, Stoppard makes madness the correlate of living in a totalitarian state.

In 1982 the reticent and reserved playwright made another bold move. His wife Miriam had long recommended he confront his reputation as a cold fish and write a realistic love story. Fiction would partly follow life: The lead character is a middle-aged playwright known for linguistic fastidiousness and anti-Marxism who is having an affair with another man’s wife while remaining close to his children. Written in a more serious key, The Real Thing is uncharacteristically direct and emotional in its dissection of marriage and the costs of infidelity. Three years later life would imitate art when Stoppard started an affair with The Real Thing’s leading lady, Felicity Kendal.

London reviews were mixed, and when Frank Rich panned the “preposterously gimmicky production” in The New York Times, the possibility of a Broadway transfer seemed to dry up. But producer Manny Azenberg was waiting the wings with the condition that Mike Nichols direct the American premiere.

The émigré wits got on like old pals, laughing at the same jokes. Working with a new cast including Jeremy Irons and Glenn Close, Nichols quickened the pace with the help of substantial cuts and thinned out the physical production. One of the witnesses to the affectionate playwright-director relationship was Irons’s wife, actress Sinead Cusack. In a La Ronde-like twist, she and Stoppard would become a couple after he and Felicity Kendal ended their affair.

Nichols’s production changed Frank Rich’s mind and then some: The Real Thing, he wrote, was “Mr. Stoppard’s most moving play, but also the most bracing play that anyone has written about love and marriage in years.” The Real Thing broke Plymouth Theatre box office records—earning its author £12,000 a week—and snagged the Tony for Best Play. His work had been well received in America, but now he was a rock star.

Lee’s biography details just how fertile Stoppard’s career was in the ’80s and ’90s, not only in theatre. Shakespeare in Love, which won him an Oscar for the screenplay he co-wrote with Marc Norman, would become his most well-known film, but before that he’d become a go-to script doctor, writing dialogue for the likes of Steven Spielberg. In 1993 he finished his “perfect play,” Arcadia. Filled with large dollops of chaos theory, mathematics, and thermodynamics, the play’s very abundance conveys “the thrill of discovering revolutionary ideas for the scientists, poets, historians, landscape gardeners, and geniuses” who inhabit two different centuries. At times playful and ebullient, Arcadia also emits a sadness born of the sense of time passing and time lost, and perhaps the end of a 22-year marriage.

As the first biography based on complete access to his journals, letters, diaries, appointment books, drafts, and notes, Tom Stoppard; A Life bears witness to a prodigious career of plays, movies, adaptations of classics, essays, lectures, and a novel. That he married three times, sired four children, wrote his mother twice a week, attended honorary events and protests on behalf of dissidents, and kept an eagle eye over many of his productions makes for a dizzying read. It can be an exhausting one as well. Lee is a lucid writer who hunts down the origins, drafts, and the impact of every Stoppard work, but why we need to know the layout of each of his homes or read a lengthy analysis of the work of Ford Madox Ford isn’t clear.

Tom Stoppard reveals the playwright as a relentless and savvy collaborator, devoted to maintaining the quality of the brand. Remarkably, he found time to attend most auditions and rehearsals, not only of premieres but also with new casts and many revivals. It was the rare New York production that didn’t involve extensive revisions.

The private Stoppard always looked on biography as an act of breaking and entering. As if to forestall the worst, he gave his chosen biographer extraordinary access and—not surprisingly—fact-checked the book. Lee positions Stoppard not only as the greatest living English playwright but as an altogether swell guy. For the most part, a deep understanding of her subject mitigates the puffery.

Until 1993 Stoppard had congratulated himself for living a charmed life. He’d became British to the core, and “success gave him an identity.” But during rehearsals for Arcadia he learned a truth about his family that shattered his equanimity: On a break at the National Theatre, Bobby’s great-niece Sarka arrived with startling news. Not wanting to revisit the past, Bobby had kept from him their identity and catastrophic family history. Sarka told him that all four of his grandparents were Jewish and had died in the concentration camps.

When Bobby died in 1996, Stoppard began to fully explore that past, making one of his many trips to his country of origin—and the city of his birth, Ziln—to meet relatives and artistic compatriots. It was with this new worldview that he wrote Rock ’n’ Roll, about the resistance to Soviet oppression from the Prague Spring to the Velvet Revolution. A Chekhovian phase followed, replete with adaptations of the master, as well as the ambitious nine-hour 19th-century Russia trilogy, The Coast of Utopia. The massive cycle reflects Stoppard’s increased interest in the choices revolutionaries must make between home and exile. And it bristles with political argument as it homes in on idealists trapped in the straitjacket of bureaucratic and military control.

Despite his actions on behalf of dissidents, Stoppard would continue to feel regret and guilt at not having known his family’s truth for so long. After 2012 those feelings came to a head when he was attacked in a Croatian novel for excluding from his “charmed life” those who died in the Holocaust. Realizing its validity, he accepted the rebuke, which became the ignition for what may be his final play, 2020’s Leopoldstadt.

Six years in the writing, Lee’s biography does Stoppard fans and scholars a service by including a play that few will have seen. She frames the work as Stoppard’s first major family play, set in four time periods beginning in turn of the century Vienna, and as the most autobiographical pronouncement of his career. The authorial stand-in is a key heir of a large assimilated Jewish family who at eight escapes the Holocaust, becomes an Englishman, and leads a “charmed life.” Eventually he grows into an unthinking writer of funny books who loves being English.

While some critics grumbled at the huge cast, the voluminous research, and what they considered static history lessons, they mostly admitted that the criticism of Stoppard as an unemotional writer did not apply to this powerful personal reckoning. Unfortunately, the pandemic halted the epic early in its West End run.

Whether they’ve known him well—and, according to Lee, not many have—most of Stoppard’s acquaintances have attested to his graciousness and collegiality. An example occurred in 2015 at a sendoff for Mike Nichols, who had died the year before. When it was Stoppard’s turn to speak to a convocation of celebrities from many corners of American culture, he told the crowd he’d always felt “overestimated by Mike.” When often asked, “Do you write for yourself or for the audience?” he said he now answered: “For the last 35 years, I’ve wanted to say, ‘No, I write for Mike Nichols.’”

Michael Bloom (he/him) is a director and author of Thinking Like a Director, as well as a new adaptation of Nathan the Wise, to be produced in Washington, D.C., in 2022.