This story is one in a series on the rise in anti-Asian hate and the American theatre’s response. Another one, about the stereotyping and objectification of Asians in the American theatre, is here; another, a round table with Asian American theatre leaders about the state of the nation and the theatre field, is here.

Asian American invisibility in the theatre can take many forms. It can mean having your story exoticized by someone else (Miss Saigon). It can manifest as actors who don’t share your skin performing a yellowface caricature of you onstage (The Mikado).

Or it can come in the form of an awards ceremony fiasco like the one in Los Angeles last week, which, if you only believed the national headlines you read, single-handedly caused the disbanding of a 46-year-old theatrical institution. The truth is far more complicated.

I should know. I was sitting next to my girlfriend, Jully Lee (she/her), when the fiasco happened.

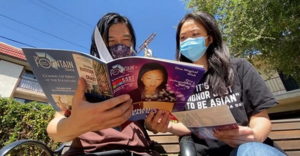

On March 30, the 31st Annual Ovation Awards (very roughly speaking, L.A.’s equivalent of the Tonys) were being streamed on YouTube, and Jully was nominated for the first time as Best Featured Actress in a Play for her performance in Hannah and the Dread Gazebo, a co-production of the Fountain Theatre and East West Players. As her category came up, the screen showed all the nominees’ pictures—except for Jully’s, as the picture above her name was not of her but of her castmate Monica Hong. After our initial shock and laughter, I posted a screenshot of the error on Facebook, where I knew our mutual theatre friends would respond with support. We only later learned that Lee’s name was mispronounced as well.

While wanting your name to be correctly pronounced or your picture to not be interchangeably used with another person’s might seem like a relatively small, even vain concern, many of our friends linked this gaffe to a general societal disrespectful attitude toward Asian Americans. After all, a rise in recent anti-Asian hate crimes was being reported everyday in the news. That’s why Lee felt encouraged to speak out on the Ovation Awards mistake and the feelings of Asian American invisibility that it engendered.

“I think in the context right now of how Asian Americans are fighting our invisibility, it felt like a big slap in the face,” Lee said in a segment on Spectrum News. “It really made me see how this wasn’t about me. That mistake represented the pain of all of us that we experience when our faces are switched, our names are mispronounced. People just don’t take the care or consideration to see us as human beings.”

The Spectrum News interview took place in the park right next to our apartment building. I accompanied Jully for moral support during the interview and ended up in a few of the shots at the behest of the reporter. Other than those 15 minutes of fame, both Jully and I imagined that that would be the end of the story.

How wrong we were.

Within a week, the Ovation Awards’ parent organization, LA Stage Alliance (LASA), would announce that it was officially shutting down for good, after dozens of member theatres joined a movement to leave the organization. This was momentous news for the region’s theatre scene, as LASA had been a nonprofit service organization for the sprawling Southern California theatre scene for nearly five decades (it was initially called Theatre L.A.). It sold tickets, promoted shows, published blogs and at one time a magazine, and generally advocated for the L.A. theatre scene. While LASA had had its problems, its ability to bring together the entire Southland theatre community for a night of celebration was still relatively singular.

None of those criticizing the organization last week, least of all Jully, had called on or expected LASA to shut down. In fact, both Jully and I are proud Ovation Awards voters. I had been nominated for an Ovation Award twice before (in the sound design categories) and brought my entire family along to both ceremonies to see if I’d win. Perhaps this is why these misidentifications stung so much: We should not have been strangers to the Ovation Awards producers.

In fact, during our Ovations voter orientation, which introduced us newbies to the organization’s rigorous rules, Jully and I were informed that LASA was instituting new policies to emphasize more diversity and inclusion. As a result, the number of Ovations voters rose from just 233 in 2015 to a record high of 300 voters in 2019. Among its new ranks were more Asian Americans than ever (including yours truly)—though to be clear, Asian American and Pacific Islanders still only amounted to a mere 5.8 percent of Ovations voters, despite AAPIs being 14 percent of L.A. County.

Still, this was a marked improvement. The orientation meeting seemed to be a validation of our worth to the community. So it has been strange to see Jully effectively scapegoated for LASA’s closing earlier this week. Glib headlines have reduced the situation to something that sounds like cancel culture run amok. Variety’s headline claimed “L.A. Stage Alliance Shuts Down After Misidentifying Asian Actress at Ovation Awards,” as if misidentifying Jully Lee were a capital offense that could tear institutions down. At best, this sounded like an actor’s vanity gone awry; at its worst, it made Asian Americans seem excessively vengeful.

In fact, it was the LASA’s board of directors who themselves shut the organization down rather than attempt to work to regain the community’s trust. Tellingly, in the days before their closure, LASA’s board had released a multi-pronged action plan to help rebuild their organization—a plan which they quickly seemed to have no interest in or ability to implement. I later learned that this action plan was something the organization had been sitting on for months.

“When COVID shut down everything in March, we figured we could use this time to really overhaul the whole program, since there was already a natural disruption,” said Michaela Bulkley (she/her), LASA’s Director of Programs and Development at the time, who helped craft the recommendations in the action plan released last week. “But then the whole staff was laid off.” LASA furloughed its entire staff at the end of June 2020, ending any talk of new changes, while also abandoning its role in bringing community stakeholders together. When LASA had an opportunity to be a guiding light through the pandemic, its leaders instead chose to downsize it into irrelevance.

That might be why the decision to even have an Ovation Awards ceremony caught many off guard and brought an even greater scrutiny to that event from people like Snehal Desai (he/him), producing artistic director of East West Players.

“LA Stage Alliance has been largely absent during the pandemic, the conversations around equity in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, and as we move towards reopening,” said Desai about the many areas he felt LASA was not addressing. “I would have liked to have been focused on what is happening in Minneapolis and the continued rise in violence against the Asian American community and not on the Ovation Awards. However, if you are going to put all your resources into this one event and it is going to be pre-recorded and made available publicly, then yes, there is going to be an expectation that the event has been vetted and errors caught and addressed.”

Indeed, the story deserves more scrutiny than the clickbait headlines would have you believe. The New York Times headline, for instance, read, “LA Stage Alliance Disbands After Awards Ceremony Blunder,” ignoring that there were multiple blunders and that Jully wasn’t the evening’s only aggrieved party. In the category of Lead Actor in a Musical, mixed-race actor Mike Millan was also incorrectly pictured, showing his white castmate Jonah Platt instead. In the Best Featured Actor in a Play category, two misidentifications occurred, one using a picture of Leo Marks instead of nominee Peter Van Norden and another using a picture of Montae Russell instead of nominee Joshua Bitton. In the latter instance, a Black actor had somehow been confused for a white actor.

Other institutional grievances soon came to light. Apparently, no effort had been made to provide captioning or an ASL translator during the awards, despite the requests of Deaf West Theatre, a company whose work was nominated in two categories that evening. And though the company Four Larks had created and co-produced the 11-Ovation winner Frankenstein, Four Larks as a company was not credited during the awards show. This was because LASA had decided against recognizing co-productions, favoring instead to credit a single entity, usually the producing partner who provided the stage. In past years, such co-productions were often recognized after due diligence from the staff had corrected the errors. But this year, having furloughed the staff and not brought them back, LASA lacked the institutional memory or personnel to properly vet each nominee.

“I didn’t see anyone in the program who had taken part in any of that due diligence in years past,” said Mark Doerr (he/him), LASA’s former director of information technology. “So they had no idea of the steps we’d take to try and prevent this sort of fiasco. It’s a shame.”

For East West Players (EWP), this was especially disheartening, as its entire season was built on co-productions with the Fountain Theatre and Pasadena Playhouse, earning those theatres multiple nominations in the process. To add insult to injury, EWP is the nation’s premier Asian American theatre, which meant excluding its co-producing credit was effectively erasing the achievements of AAPI artists. According to Desai, this struggle was nothing new. “We have been pushing for this equitable recognition of co-producers for five years now,” Desai said. “Show by show, I had to have that fight every time.”

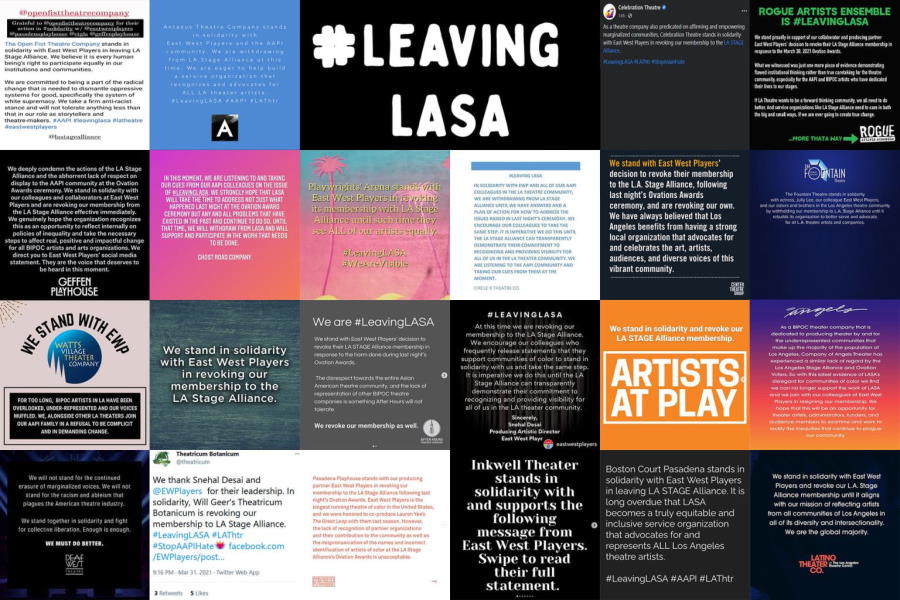

Sensing a possible momentum shift, Desai released a statement decrying the exclusionary practices of the Ovation Awards. But more than releasing a statement, Desai knew he needed to take decisive action—one that would cut through the mere noise of outrage. In his statement, Desai revoked East West Players’ membership in LASA and encouraged other theatres to do so with him in solidarity, using the hashtag #LeavingLASA. When the dust had settled, over 50 theatres, including some of the largest, like Center Theatre Group and Pasadena Playhouse, had joined Desai’s #LeavingLASA movement.

“In honesty, there was no coordination. I thought, ‘We’ll see if others speak up or not’ and that will make its own statement,” said Desai. “And then folks just started releasing statements…They just started to take their own initiative and speak up and speak out.”

For the first time in a long time, or perhaps ever, the entire community seemed ready to listen to the leadership of one of its Asian American members. Many decades before, the protests against Miss Saigon did nothing to stop that show’s eventual 10-year Broadway run, not to mention a Tony Award for a yellowfaced Jonathan Pryce.

Things were different now. Once Desai gave his protest a name, other theatres came out with their own criticisms of other aspects of the Ovations, but it was Desai who read the room and intuited that a mass movement was possible.

“By speaking out, we just provided the catalyst,” said Desai. “The pressure had already been building; we just helped spring the first leak that caused the dam to break.”

The dam was showing signs of cracking well before LASA disbanded. Faced with an increasing void of leadership from LASA, many theatres had taken it upon themselves to form smaller scale alliances. For example, the Alternative Theatres of Los Angeles boasts 65 member theatres in its collective.

Asian Americans were also on the front lines of these efforts. Playwrights’ Arena artistic director Jon Lawrence Rivera (he/him) told me that he had begun what he calls the “L.A. BIPOC Artistic Directors’ Group,” which formed last year but ramped up to meeting once a week in March. So far there are 21 member companies, including Native Voices at the Autry, Watts Village Theatre Company, Latino Theatre Company, and Celebration Theatre, to name just a few.

“It’s a group of BIPOC artistic directors looking to create a collective that could ask for multi-year sustainable funding and support from various funders,” Rivera said. Rivera is somewhat of a stickler for BIPOC theatrical representation. (Full disclosure: I’m an associate artist at Playwrights’ Arena.) At his theatre he has already implemented his own quantifiably robust standard of diversity.

“In recent years, we mandated a 50/50 casting policy, where all productions must have at least 50 percent BIPOC artists,” Rivera said.

The BIPOC Artistic Directors Group happened to have a meeting on the same day of LASA’s closing announcement. Though the group did discuss what a new LASA might look like, Rivera said it was only a brief mention, as they “had other pressing business that needed time to address.” With or without LASA, the show will go on.

Asian Americans have felt invisible for so long that, when suddenly faced with extreme visibility, we can be somewhat caught off guard. That’s what happened March 16, when a white gunman opened fire on three Asian-owned businesses near Atlanta, killing eight, six of whom were females of Asian descent, in the largest mass shooting since the COVID pandemic began. Though anti-Asian violence was already being reported daily in the national news, the Atlanta shooting was a rallying cry the entire country could no longer ignore.

In Atlanta’s wake, I attended a Zoom affinity space for Asian American theatre designers (I am a sound designer). It was run by Clint Ramos (he/him), a Tony-winning designer who, since last summer, has been involved in similar affinity spaces for a group of prominent BIPOC designers called Design Action. Ramos explained the need for such spaces.

“From my experience, America has convinced us that our role in this country is to be invisible and that privileges come with that invisibility,” Ramos said. “I know that I’m programmed culturally to keep my head down and keep on working and suffer through adversity. We already start at a base line of invisibility, so it almost feels antithetical to our being to be visible and take up space and express any sort of emotion.”

The beginning of the pandemic itself was a reckoning for Asian Americans in particular. A spike in anti-Asian violence and harassment has resulted in at least 3,795 anti-Asian hate incidents in the past year alone. This left Asian American theatre artists like me looking for ways to respond creatively. The pandemic had halted production on a 10-minute autobiographical piece about my high school years in the San Gabriel Valley, a suburban Asian American enclave. We were about to head into tech when the country shut down and the production with it.

I had grown up in the “SGV,” as I call it, and had never seen a similar Asian American plurality depicted in media or onstage. I believed my play would help remedy this. To his credit, Company of Angels artistic director Armando Molina (he/him) expressed immediate interest in developing a full-length SGV play with me long before “Stop Asian Hate” was trendy.

“The San Gabriel Valley is America, plain and simple,” Molina said. “This transplantation and blending of cultures is so beautifully American. But like so many other communities of color that make up the majority of Los Angeles, this community has never been depicted onstage or screen, making it invisible to the larger population. Whether it’s Trump’s comments about Mexicans being drug dealers and rapists or referring to COVID using a slur against Asians, if you are not countering that narrative you are actively reinforcing an environment in which it can persist.”

Indeed, numerous violent attacks have been reported in the SGV against the Asian American community, including an attack on an elderly couple that left an 80-year-old Chinese woman senselessly beaten to death in the streets of Pasadena. Today a narrative about vibrant communities like that in the SGV seems all the more necessary and urgent.

“I believe racism is rooted in the fact that we don’t know enough about each other,” said actor Steven Ho (he/him), who was slated to play me in my play. Ho (no relation) may point the way forward for Asian Americans to emerge stronger from this situation. As live theatre shut down last year, social media became the creative outlet for many. Zoom productions and Twitch streams became our new stages.

Moreover, because social media platforms do not have a centralized gatekeeper structure, almost anyone with any type of content is welcome. Though Ho is pursuing acting, his day job is as an emergency room technician. In December, Ho began posting his daily homemade video series “Tips from the ER” on TikTok. Since then he’s been earning a million new subscribers a month (yes, you read that right). So when the new wave of anti-Asian violence began to spike, culminating in the Atlanta shooting, and Ho wanted to respond, the only gatekeeper he had to answer to was himself.

“For a split second I selfishly thought, Will I lose followers if I use my platform to give a political statement?” Ho said. “How crazy is that? That my biggest fear could be losing followers while our community is being beaten and killed. No. If there’s a way to use my platform to help, I will.”

Now, with LASA gone as a gatekeeper for Los Angeles theatre awards, perhaps a new, better system will emerge. What comes next is unclear, but one thing I know for certain: Asian Americans, with our unique names and faces, will remain a vital and visible part of it.

Howard Ho (he/him) is a playwright, composer, and YouTuber. Nominated twice for Ovation Awards in sound design, he has designed shows for Theatreworks Silicon Valley, Center Theatre Group, Deaf West, East West Players, and Playwrights’ Arena, among others. His YouTube videos analyzing Hamilton have earned millions of views and have been recognized by Lin-Manuel Miranda. He holds a musicology degree from UCLA and a Master of Professional Writing from USC.