This story is one in a series on the rise in anti-Asian hate and the American theatre’s response. Another one, a round table with Asian American theatre leaders about the state of the nation and the theatre field, is here; another one, about the controversy around the L.A. Ovation Awards, is here.

A few years ago, I was walking down the street in Portland during the 2017 TCG National Conference. I was speaking on the phone to my mother in Vietnamese. I walked past a group of young men, and behind me I heard what sounded like the word “chink.” I didn’t turn around, I walked faster. I started shaking.

Maybe I misheard it, I thought. Maybe I was just being paranoid. Even now, I tell myself that maybe I didn’t hear what I thought I heard. But if it wasn’t what I thought I heard, why do I still think about it?

That’s the thing about being Asian in America: You are constantly telling yourself that what you’ve experienced is not that bad. You excuse the ignorant comments of “go back to where you came from,” the “me love you long time” and “ni hao ma” jokes, the being mistaken for the other Asian person at work. It’s just words, we are told. You should learn how to take a joke. So we swallow the discomfort.

As Cathy Park Hong wrote in her bestselling book Minor Feelings:

When I hear the phrase, “Asians are next in to be white,” I replace the word “white” with “disappear.” Asians are next in line to disappear. We are reputed to be so accomplished, and so law-abiding, we will disappear into this country’s amnesiac fog. We will not be the power but become absorbed by power, not share the power of whites but be stooges to a white ideology that exploited our ancestors. This country insists that our racial identity is beside the point, that it has nothing to do with being bullied, or passed over for promotion, or cut off every time we talk.

We are usually on the sidelines when it comes to storytelling; we say words but never make any kind of impact. We are so invisible that many people (including many Asian Americans) don’t know our own history in this country, and how that history is rife with exploitation, violence, and exclusion. But Asians are also fed to the prison industrial complex, deported, and killed by police officers kneeling on our necks. But because those stories don’t fit into the “model minority” myth of Asians being affluent and successful, you probably haven’t heard them.

Being Asian in America is a continual process of being gaslit by the people around you and, most insidiously, by yourself. When the wider culture tells you that your stories, your face, your people are not worthy of attention, you make yourself smaller. You tell yourself that your feelings, your pain, your rage is not worthy of attention.

After all, if you’re invisible, you can’t bleed.

May Adrales (she/her), director and newly named Lark Play Development Center artistic director, told me that while she’s experienced racism, she “was purposely not taking a lot of space, because I didn’t want it to detract from other movements, from Black Lives Matter. And I think that that reticence was respectful. But it also wasn’t allowing for greater solidarity and building a movement against the violence.”

With the murder of six Asian women in Atlanta, amid a rise of violence and hate crimes against Asians in America, we now know that invisibility can kill us.

According to the Asian American Performers Action Coalition, in the 2018-19 theatrical season in New York City, Asian American actors were cast in just 6.3 percent of all available roles, Asian American playwrights and musical theatre writers made up just 4.9 percent of all writers produced, and Asian American directors oversaw just 4.5 percent of all productions.

As AAPAC said in their own recent statement condemning anti-Asian violence:

In our own industry, we have witnessed this same white supremacist narrative in the form of the exotification, dehumanization, and erasure of Asian men and women on America’s stages. Words matter. Representation matters. The perpetuation of hideous and inaccurate stereotypes, only seeing our stories via a white lens, and removing us from the American narrative through exclusion are all directly connected and have their ramifications. They dehumanize us to the point that some believe we are expendable enough to further erase with cold-blooded murder.

The American theatre has historically sidelined Asians in two main ways: yellowface—hiring white actors to play Asian roles—and stereotyping. Yellowface only very recently became a faux pas in theatre, and only because a critical mass of theatre artists protested against it.

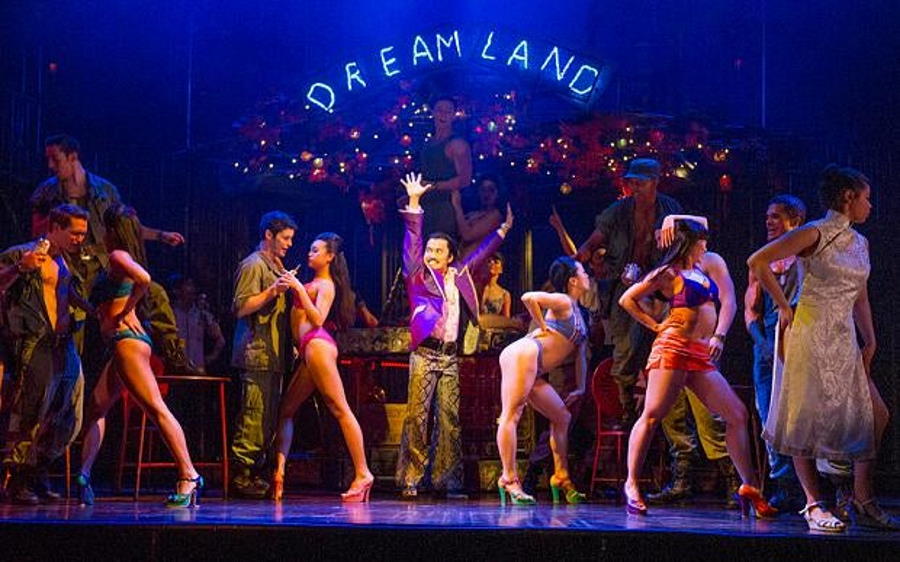

I have written about the theatre field’s love of Asian stereotypes. Even before the pandemic, Miss Saigon was still touring around the country and The King and I was touring worldwide. There has been no similarly widespread reach for a play written by Asian Americans. Mainstream theatre audiences would still rather see Asians as foreigners in need of white people’s help than as equals.

American stages have perpetuated the sexualization and dehumanization of Asian women, from frequent performances of Madama Butterfly to its knockoff Miss Saigon. In the popular South Pacific, Bloody Mary gives her Polynesian daughter Liat away to an American sailor as a gift. Liat doesn’t speak in the musical. Silent and submissive, she takes off her clothes immediately after meeting Lt. Joseph Cable. She is merely an object to be looked at and taken.

Miss Saigon is the story of a Vietnamese prostitute named Kim. We never learn much about her: What are her dreams? What was her village like before the war? What does she like to eat? The only thing we know about Kim and her fellow prostitutes is that they all want to go to America. Their entire characterization is about idolizing whiteness. Like South Pacific, Miss Saigon positions Asian women as playthings of white men, minus any aspirations, dreams, agency, or last names. Their only job is to service white men. It’s “me love you long time” as a musical.

I’m not saying sex workers should not be portrayed onstage—Among the Dead by Hansol Jung, for instance, is a brutally frank play about Korean comfort women that doesn’t romanticize the history and instead highlights the resilience and inner life of those women. Bottom line: You shouldn’t portray a sex worker without also showing why she is in that position. In the case of Kim and Miss Saigon, it’s because American imperialism has destroyed her country. It’s because of the American appetite for Asian women’s bodies. You cannot have prostitution without demand.

But that’s not what white audiences want to see. They want Asian women who are subservient and self-sacrificing, so that white audiences don’t feel complicit in Kim’s pain. They can write it off as, That’s just the way those people are. They want to see American soldiers as flawed heroes, but still heroes—not as sex traffickers and bannermen of the American war machine.

When you sexualize an Asian woman without giving her agency or a personality, when you make her a vessel for white guilt, you contribute to stereotypes about Asian women. You make her invisible. You make her less than human. And when she is murdered in Atlanta, you can dismiss her as “temptation.” See how easily that excuse of the killer was taken up by the police and parroted by the media. America would rather see Asians as objects and stereotypes, in part because that’s what American popular culture has been giving them.

These stereotypes also affect the way Asian Americans are treated as theatre workers. As Adrales told me, production teams don’t know what to do with an Asian woman in a position of power.

“Many attempts of assertiveness were met with reprimand and ‘difficult to work with,’” she told me. “When I tried to create space for myself to do my job at the helm of the production, I was criticized and in subtle ways retaliated against. Production managers have undermined my authority because of these instances, souring my reputation with other theatres and talking badly about me with members of my creative team—even as I see my white male counterparts gain respect from the very same behaviors.”

This is more than the usual misogynist double standard—it is that, definitely, plus racism.

“I think it’s largely because what those with authority/power saw was an Asian woman who would comply and remain obedient and grateful, and any disruption of that stereotype was seen as an egregious aggression and incompetence,” Adrales said. “It’s taken me a very long time to come to terms with that racism; even articulating it now is still somewhat revelatory.”

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, New York City was experiencing something I had never seen before in my 10 years of covering theatre: Asian American playwrights being produced in record numbers. Cambodian Rock Band by Lauren Yee was running at the same time as The Headlands by Christopher Chen, Endlings by Celine Song, and Suicide Forest by Haruna Lee. Yee was one of the most-produced playwrights in the American nonprofit theatre that season. Before then, we were lucky if we got one production a season at a major Off-Broadway or regional theatre.

It seemed that Asian American plays were finally having a moment. These weren’t just stories about immigrant parents and their kids, or trauma porn, or merely identity-driven. They were playful and edgy, and they showcased Asian faces as human, with individuality and variety, with characters who loved rock music or ocean diving.

That moment was hard-won. I talked to a number of Asian American artists for this story, and all agreed that there is a “bamboo ceiling” in terms of how big a budget level they can expect to work with. For one thing, you normally won’t normally see a predominantly white theatre’s Asian American show—or any show by BIPOC artists—on the mainstage. It’s usually in a theatre’s secondary space.

As a director of new plays primarily written by playwrights of color, May Adrales knows this tendency well.

“Typically I’m in the smaller spaces,” she said. “Most of those theatres formulaically do their person-of-color show in February or March. They don’t do it as the big spring closer or the big fall opener.”

As Adrales and a number of artists told me, theatres will usually program a BIPOC show to fulfill the mandates of a diversity grant. Which means they don’t necessarily believe their white subscriber audience will actually see it or relate to it.

Over her career, Adrales has noticed that Asian American artists often have to “prove that there is a demand for these stories.” A common question she’s been asked is, “How could an Asian show possibly attract enough people to fill a bigger space?” Adrales concludes: “People think that Asian stories are not universal,” but “exotic outsiders to the mainstream.”

Playwright Lauren Yee (she/her) faced similar hesitancy when she was looking for commercial producers who might help transfer her hit play Cambodian Rock Band to Broadway. It had done well regionally and Off-Broadway, selling out and extending at multiple major theatres. But when it came time to talk about Broadway, Yee hit a wall.

“It seems harder to get an Asian American show on Broadway than it is to get a movie or a TV show made,” said Yee, who is one of the writers for Pachinko on Apple TV+. Indeed, to date, there have been many more major Broadway productions about Asians by white writers than Asian stories by Asians.

Regardless of authorship, plays with Asian characters at least mean that Asian actors can find work—indeed, it seems to be the only time they can hope to get work. According to AAPAC, Asian American and Middle Eastern actors were the least likely to be cast outside their race. If the role isn’t racially prescribed, 80 percent of the time it will go to a white actor.

Even when they are cast, Asian American actors are seldom embraced as whole people, or as the heroes. Actor and AAPAC leader Pun Bandhu (he/him) was once brought into a major Off-Broadway theatre to play an Asian American side character. He wasn’t given an opportunity to make the role deeper or to change it, because the director was white, the playwright was white, and the artistic director of the theatre was white. “You just felt like a cog in a wheel,” Bandhu said. “It’s really subtle things that are so hard to articulate, but it’s a real thing that’s felt, and it’s totally systemic.”

Bandhu described working in theatres run by white producers as akin to being a guest in someone else’s house. “You’re the show of color this season, you’re fulfilling some sort of diversity initiative, it feels like a diversity hire,” he said. “And so there’s this feeling of like, ‘Oh, we’re so glad you’re here.’ But there isn’t the level of engagement where they’re interested in you other than what you bring in terms of race.”

There are also economic consequences for siloing BIPOC creators on smaller stages: It enshrines a wage gap between BIPOC and white artists. Because pay rates and profit-sharing are dependent on how big a theatre’s house is, the smaller the house, the less money there is to be made. The deck is stacked from the get-go. As Yee put it, “If you produce all women and BIPOC artists on the second stage, and you do all your white men on the big stage, those white men will make more for the same amount of work.”

Indeed, AAPAC’s study points out that for every $1.70 a white actor makes, a BIPOC actor makes $1, due largely to this sidelining of BIPOC plays and spaces. It also limits the impact our stories can have: When a white play can get 500 pairs of eyes on it per night, the 100 viewers that a BIPOC show has in the second stage is minuscule in comparison.

This inequality is also felt sharply between theatres of color and predominantly white institutions. Theatres of color have historically been underfunded compared to white theatres (I’ve also covered this topic before). AAPAC looked at the 990 forms of the 18 largest nonprofit theatres and 28 BIPOC theatres in NYC, and found that the white theatres got over $170 million in funding, while BIPOC theaters received $12.2 million in funding.

It’s not just in NYC. As the Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists (CAATA) pointed out in a statement, “When looking at government funding alone, the predominantly white institutions received $30.7 million of government funding while BIPOC theatres received under $5 million. It is evident that being historically underfunded normalizes deprivation and rigidly employs structural social control.”

“If you look at the budgets of theatres of color across the country, they’ve been stagnant,” said Ralph Peña (he/him), artistic director of Ma-Yi Theater Company. “Because funders, both private and public, think of us as an economic subset of American theatre.” In other words, because theatres of color usually program stories about one particular ethnic community and serve those audiences, they’re considered “small” and “niche,” said Peña. “We’re specialized, we cater to specific communities. And so our funding has been kept at that ceiling, so we never get to grow beyond that.” It’s hard to grow when you keep getting the same amount of money every year.

When white theatres want to program “diverse” shows, on the other hand, they will often get specialized funding to do so from foundations (which don’t normally fund theatres of color). Then these same white theatres will ask theatres and artists of color to serve as their marketing arm, to spread word about the show in their specific communities. Yee told me how she had to act as a community liaison for her plays to make sure that, for instance, Cambodian Americans would turn up for Cambodian Rock Band.

As that labor is not recognized, it is also not compensated.

“You have to change the way you value our work,” said Peña. “Because no one else at these PWIs [predominantly white institutions] are responding to the needs of our community. Or if they do, it’s almost always carpetbagging. They’re there to sell tickets, but they don’t have a relationship with the communities.”

Just as Asian shows are seen as exotic oddities rather than universal, Asian American theatres aren’t considered national theatres by funders, even though it is companies like Ma-Yi, Theater Mu, and East West Players that have historically nurtured Asian American artists when white theatres would not work with them, and told Asian American stories before there was a financial imperative. Even now, in quarantine, Ma-Yi is providing $500 micro-grants to BIPOC artists.

Theatres of color are responsible for nurturing many BIPOC artists, who in turn are not seen as legitimate artists until they’re produced at white institutions. It’s not that Asian American artists shouldn’t work at the most prestigious institutions or get their Broadway credit (and money). But when what is considered prestigious are white institutions, and Asian American theatres are seen as niche and less worthy of attention, that’s a problem. At the recent Ovation Awards in Los Angeles, organizers had no problem mentioning white theatres whose shows were nominated but made no mention of East West Players, which had two shows nominated (the awards also misidentified an Asian nominee by mispronouncing her name and showing a photo of another Asian actor in her place).

Peña sees a link between the sidelining of Asian American stories and the surge of recent violence against the community—and the urgency of his theatre’s work to counter that.

“We do the humanizing of Asian faces for America,” he said of Ma-Yi’s work. “We tell Asian stories from Asian artists, with Asian agency and centering Asian lives, therefore humanizing Asian lives. That’s our function. And so when we do that, it’s harder to choke somebody on the subway until they’re unconscious.” He then added for emphasis, “That is our function, and you need to empower us to do that, because otherwise we just don’t have the resources.”

When I write or think about anti-Asian violence, I'm not talking about microagressions, although that is harmful too. It can become violent if you grow up in an environment where that is your everyday reality, & the racism makes you hate yourself & where you come from. (1/13)

— Tracy La (@_TracyLa) March 31, 2021

Microaggressions aren’t the same as full-scale violence. And better representation isn’t the only answer to Asian hate. But the former president and many in his party have consistently referred to COVID-19 as the “China virus,” leading directly to the past year’s increase in hate crimes. And violence does not come from nothing. Microaggressions, erasure, stereotypes, and exoticitization provide the soil in which violence can grow. Also indifference to violence: How else to explain people looking away when a 65-year-old Filipina woman is being kicked repeatedly in the head in midtown Manhattan, as if she doesn’t exist?

It wasn’t until the Atlanta shooting that Stop Asian Hate became a hashtag that reverberated outside of the Asian American community. Hate crimes against Asian Americans had been happening before last month, but most people didn’t want to hear about it. The day before the Atlanta shooting, 32 Vietnamese Americans were deported back to Vietnam, even though they had already served time in jail for their misdemeanors. You probably hadn’t heard about that because of how normal it is for Asians to be invisible, for our stories to not be worth mentioning.

As Tracy La, executive director of VietRise, an advocacy organization for Vietnamese immigrants, said on Twitter: “When I write or think about anti-Asian violence, I’m not talking about microaggressions, although that is harmful, too. It can become violent if you grow up in an environment where that is your everyday reality, and the racism makes you hate yourself and where you come from. If the microaggressions and racism restructure/rewire your connection to your identity and make you hate yourself and your community, that is psychological violence.”

How can we learn to acknowledge our history and learn to be proud of who we are when the popular culture insists on shoving us to the side or worse, making us the butt of the jokes? When we are seen as invisible, we internalize it. That’s why Asian Americans are the ethnic group least likely to report a hate crime. We have gotten used to swallowing our own pain.

This is why I am tired of solidarity statements. I do not want another theatre to release a statement saying they condemn Asian hate, or that they stand with the Asian American community, without reckoning with their own role in sidelining Asian voices. Because we did not make ourselves invisible. We have been made invisible.

Lately I’ve been taking comfort in my own community as we rally and support each other, and learn to vocalize our own truths, some of us for the first time. After the Atlanta murders, Adrales and the Lark hosted a virtual convening where anyone could attend, process, and find support. Said Adrales, “If we can, as an entire BIPOC community, recognize that many of our struggles are different but many are the same and that one injustice to one group is an injustice for all, I’m hoping that will sow the seed for other conversations and coalition-building with other social justice movements.”

There is no easy answer for what happens next (though CAATA has some suggestions). Even as I write this, in the darkness of this particular moment, I remember the light that shined briefly: the moment before the pandemic when, for the first time, there was a proliferation of Asian stories that showcased our individuality. And I am buoyed that for the first time, an Asian American story, Minari, is nominated for Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards.

I am reminded that artists and activists have been banging against the doors of the white establishment for centuries, despite those pretending not to hear or see. The outcry of this moment shows that maybe people are finally listening.

And when theatre comes back, I want more stories, bigger stories, and for Asian faces to take centerstage and for all audiences to see themselves in us—to see us as not a them, but a you. Our history is American history. Our stories are American stories. One thing is for sure: Being invisible is no longer an option. The price is too high.

Diep Tran (she/her) is a former senior editor of this magazine. She is currently the managing editor of VietFactCheck, a bilingual misinformation education project for the Vietnamese American community that has been featured in The New York Times, Vox, and NPR.