This story is one in a series on the rise in anti-Asian hate and the American theatre’s response. Another one, about the stereotyping and objectification of Asians in the theatre, is here; another, on the controversy around the L.A. Ovation Awards, is here.

Last year, anti-Asian hate crimes increased by 149 percent in 10 of the nation’s largest cities. More broadly, 58 percent of Asian Americans say it is more common for them to hear people to express racist or racially insensitive views about people who are Asian than it was before the coronavirus outbreak.

Hate crimes against Asian Americans have a long history in this country, but for many, the impact has come closer to home during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the early months of the virus’s spread, former President Donald Trump referred to the coronavirus as the “kung flu” and the “China virus,” regurgitating and reinforcing conspiracy theories about economic control by the Chinese government and wet markets in Wuhan.

Not coincidentally, Asian Americans have become targets for the resentment many people have felt about the losses the pandemic has visited on them. A worst-case scenario unfolded on Tues., March 16, 2021, when a white man, Robert Aaron Long, killed eight people—six of whom were Asian women—at massage parlors in Georgia.

As it came amid a rise in anti-Asian hate, many believe the massacre in Atlanta constituted a hate crime. According to the Department of Justice’s 2019 statistics, 52.5 percent of offenders in hate crimes are white; Georgia passed a long-awaited hate crime bill after the killing of Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, Ga., last February. But Cherokee County police seem to have taken as face value Long’s claim that he was not motivated by race but by his attempts to eradicate a sex addiction. As of this writing, Long has been charged with eight counts of murder, but no hate crime.

In the weeks since, there have been protests, vigils, and calls on social media to #StopAAPIHate. On the ground in Atlanta, artists have painted murals in honor of the victims, and activists have encouraged solidarity between the Asian American and African American communities. The theatre field has mobilized particularly rapidly, with the Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists (CAATA) joining Theatre Communications Group, the publisher of this magazine, in producing a video featuring leading lights of Asian American performing arts denouncing hate, and in launching a hashtag #HadaBadDay to collect stories of hate incidents against Asian American and Pacific Islander people.

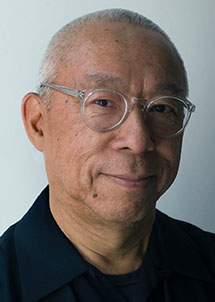

Meanwhile many Asian American theatres have issued statements, turned their buildings into spaces for healing, and begun to create art in response to this moment. American Theatre spoke with an intergenerational group of Asian American theatre leaders across the country about their experiences over the past year and how theatre can be a part of the change. The leaders interviewed include Tisa Chang (she/her, Chinese American), co-founder and producing artistic director of Pan Asian Repertory Theatre in New York; Ping Chong (he/him, Chinese American), co-founder, and Jane Jung (she/her, Korean American), managing director, both of Ping Chong & Co. in New York; Lily Tung Crystal (she/her, Chinese American), artistic director of Theater Mu in Minneapolis, Minn.; Ely Sonny Orquiza (he/him, Filipino American), co-artistic director and founder of the Chikahan Company in San Francisco; Michelle Pokopac (she/her, Korean American and white), actress and co-founder of East by SouthEast in Atlanta; and Samson Syarath (he/him, Laotian), artistic director of Theatre Diaspora in Portland, Ore. Below are excerpts from those conversations.

KELUNDRA SMITH: Asian Americans have struggled for visibility in the American theatre for centuries. Why do you think this is the case?

TISA CHANG: It’s mind-boggling how bias and intolerance have been pervasive. I started performing as an Equity dancer and actor doing summer stock in 1959. I did quite a few musicals, as well as The World of Suzie Wong, a very controversial play about a Chinese prostitute. I knew Asian artists could do more, and my work since founding Pan Asian Rep in 1972 has been to try to equalize the field and say that we too can play Clytemnestra. We too can reach the zenith of American theatre.

MICHELLE POKOPAC: A lot of people who we consider pioneers in the American theatre come from a similar background, usually a white male. Whenever it comes to stories that tell of the different, non-white perspective or experience, ideally you would have someone of color to tell/create that story. Theatre has always been white-centered, so when you have whiteness as the pillar it’s hard to make room for everyone else. And when you do tell other stories, they’re no longer considered mainstream and they’re not given that space to share, so you have terms like “theatres of color.” It’s always relative to whiteness, and Asians are always seen as foreigners.

SMITH: Have you, or has your theatre, been the target of anti-Asian hate since the COVID-19 pandemic started? If so, what has been your response?

PING CHONG: I live in Chinatown, and there have been a lot of attacks in the area. I have two elder sisters who are vulnerable. It’s real.

JANE JUNG: I think it’s important to distinguish regional differences. There have been a lot of attacks reported, especially in the Bay Area. Then, with the attacks in Atlanta, that’s a specific experience with victims that are outside of a metropolitan area. While in some ways it’s been a shared processing and collective grieving across the country, it’s important to highlight the differences.

ELY SONNY ORQUIZA: Last summer, when I began the Living Document for BIPOC artists in the Bay Area, I received so much racist email. The Living Document chronicles the extent of white supremacy in the theatre industry, and invites all Bay Area artists to share accounts of microagressions and overt racism that they have experienced in the theatre. The most upsetting, disturbing, and distressing message I received was someone calling me monkey. There is the constant attempt to silence BIPOC voices, but this document garnered 600 testimonials on the first day of people sharing their experiences.

POKOPAC: I have not had any physical attacks, but I have been verbally harassed. One time I was walking my dog in southwest Atlanta and people were shouting at me from their cars. They’ll call me Chinese or say, “Watch out, the Chinese are here! Go back.” I have had virtual attacks on the Clubhouse app. I was in a room for the Asian community, and all of a sudden this one guy said, “You all look like you eat dog in this room.” I just feel like hate has found its redirection into another marginalized group.

SMITH: When you heard about the murders in Atlanta a few weeks ago, what was your reaction?

CHANG: What happened in Atlanta was someone targeting the most vulnerable—the elderly, women, new immigrants, people who speak English as a second language—people who are the least likely to report crimes. It’s sad. I remember that I was sent by the National Endowment for the Arts in the 1980s to review the Springer Opera House in Columbus, Ga. I was booked in a Hilton hotel as a distinguished guest, and they put me in a room by the service elevator near the kitchen. There’s a lot of lingering racism.

POKOPAC: I didn’t hear about it until the next day, and by then a few of my Asian friends texted me. It was a long and heavy day. I used to live off of Cheshire Bridge and Lindbergh [where one of the shootings happened], so I’m very familiar with the area. [The shooter] was claiming it was a sex addiction; if you know that area, you know there’s an adult novelty store and strip clubs. I appreciate the importance of bringing awareness to black-market sex work and human trafficking, but these women were massage therapists. Even though I didn’t know them personally, when it affects people who look like you, it hits a different way. This past year, I’ve been worried about people like my mom, because for some horrible reason a lot of older Asian men and women have been attacked as well. That could be my mom.

ORQUIZA: I was shocked but not surprised because of the hate crimes that had been going on in 2020. The former president’s rhetoric made coronavirus synonymous with Asian people. The shooting that happened in Atlanta was a capstone. It’s sad to me that it took a shooting to make people see that anti-Asian hate crimes exist. As storytellers in the theatre, we have a responsibility to combat harmful stereotypes.

SMITH: The Asian “model minority” myth, and a history of being seen as silent or being actively silenced, have become topics of discussion around activism in the Asian American community. Where does that fit into the larger discussion around dismantling white supremacy?

LILY TUNG CRYSTAL: The Asian American community is not a monolith, but I do believe that across many Asian cultures, there’s this idea that in Chinese we call “Chi Ku,” which means eating bitterness. We’re often taught to keep our heads down to stay safe, to survive. A lot of us are fighting against not being too loud or the feeling that we shouldn’t complain. It’s easy to find us invisible or pick on us because historically we’ve been less vocal. White supremacy also forces us into silence. There’s a myth that racism against AAPI’s doesn’t exist, so when we are vocal, people often dismiss our experiences or consider our grievances illegitimate.

JUNG: I’m not comfortable taking up a lot of space and it’s been a journey to recognize that, and also claim that space without feeling apologetic. I know that plays into some perceived stereotypes, but it’s also tied to how I was brought up, and in some instance specific cultural influences. On the one hand, I have come to this point after a lot of experiences where it’s important to recognize and not deny my background, but also challenge myself and others to defy those expectations. Everyone has their own relationship and journey with that.

POKOPAC: There’s an unsaid guilt of the model minority myth, especially following the Black Lives Matter protests. There’s racism and colorism within our communities. I think it needs to be brought up more. We’re taught to be the “acceptable” person of color, and that we have the same privileges as the white man when we don’t. It’s gaslighting. It’s had a horrible history of pitting us against the Black and Latinx communities. Being a half white/half Asian person who is Asian passing, that is a duality that I have been faced with my entire life.

SMITH: Along those lines, over the past few months, a lot of people have brought up the need for Black and Asian solidarity. What’s your perspective on that?

CHONG: There is a lot of tension between Black and Chinese poor communities, because it reinforces racism on both sides. The press is always demonizing Black people, so new Chinese immigrants think they have to be fearful of Black people. It makes it harder to take it out on the white master. This pits the two communities against each other, when they should be on the same side, because in this country the poor are never served first.

CRYSTAL: Over the past year, Theater Mu has been fighting anti-Blackness in our own community and standing with the Black community in the Twin Cities and across the country. After George Floyd’s murder, we focused on social justice and shared articles about how to support the Black community. We’ve been in conversation with Penumbra through the Twin Cities Theatres of Color Coalition; we cleaned up after protests, printed posters. We also hosted the RE:Plays Festival, where we hired three pairs of Asian and Black playwrights and presented new works by them in a virtual space.

ORQUIZA: We have a rich history of Black and Asian solidarity in the past. I think it goes back to the 1955 Bandung Conference [in Indonesia], when Asian leaders and African leaders came together to discuss decolonization. What’s wonderful is that we have that history to look at in order for us to move forward and build a stronger foundation together.

SYHARATH: A lot of predominantly white organizations try to pit communities of color against each other, but we realize that coming together is how we have power. To me, it’s about collaboration, reaching out to other organizations of color, supporting them, and giving when you can.

SMITH: How can theatres, and the theatre community in general, support the Asian American community at this time?

CHANG: I wish we had a fairer share of the money pot. Many of us are small in budget size and stature. We are not Lincoln Center, and we can’t compete with those deep pockets. I am beginning to see more theatres of color be recognized with grants and I want to see more.

CHONG: My whole career has been about not being supported by the white theatre world. The person who first supported me was Ellen Stewart at La MaMa, and it still is an artistic home for us. That’s been the reality I worked in all my life. The theatre community needs to think long-term about supporting people of color, both backstage and onstage. If it’s not long-term, it’s meaningless. This country is moving into a different complexion. It’s not going to be what it’s been.

CRYSTAL: Acknowledging that the AAPI community is in pain is a first step. I can’t tell you how many people reached out to me that week as if nothing was going on. We feel invisible in many ways because people aren’t aware that it’s even an issue. Asian Americans are being injured and killed.

JUNG: First and foremost, I’d like to see the American theatre at large tend to and check in with staff and folks within their communities. I’ve seen a lot of solidarity statements, and there is good sentiment, but I’m left with questions about what specific actions people are willing to take.

ORQUIZA: Funding and producing works that are made by, acted by, written by, and directed by Asian Americans would be a start. Providing leadership positions and other artistic opportunities to engage—not just the artists of now but the next generation. Speaking about the Bay Area, there is a lack of Asian American stories being told onstage. The theatre companies can do more to tell stories that reflect the population of the region.

POKOPAC: I feel like I’ve been the go-to spokesperson for the Atlanta theatre community when it comes to Asian things. We’re not a monolith, and I didn’t ask to be that person. When I am asked that question, I feel like we already know the answer, but we don’t know the first step. I don’t know why it has to be my burden to answer that. I don’t understand why it has to be people of color’s burden to answer the questions for people who don’t have to deal with this.

SYHARATH: We’ve had a lot of donations recently. The fear is that this is a one-off thing because of what’s happening in the news. It’s worrisome because the work needs to continue to happen. A lot of predominantly white organizations that I’ve talked to have mentioned how to bring more BIPOC-identifying people to their table. I often ask: Why don’t you go to their table? Why is it always about you? If you want things to be more equitable, how about you rebuild your table?

Kelundra Smith (she/her) is a contributing editor to American Theatre magazine. kelundra.com