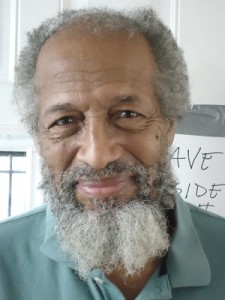

Douglas Turner Ward, one of the founders of the seminal Negro Ensemble Company, died on Feb. 20. He was 90. The following tributes were compiled by Erich McMillan-McCall.

From the Page to Life

Douglas Turner Ward was a giant in the American theatre, but he was also my director, my mentor, my friend. In 1966, he wrote an editorial in The New York Times, titled “American Theater, for Whites Only?” A Ford Foundation grant enabled him to co-found the Negro Ensemble Company. The NEC became a gateway into the theatre for generations of Black actors, directors, designers, playwrights, and stage hands. It also opened the door for the establishment of women’s theatre, LGBTQ theatre, Asian American, Latino, and Native American theatre. In addition, Doug began to develop a canon of Black American plays and their writers. No one had previously done that, and today no one continues that work except for the NEC.

On a personal level, Doug made me the artist I am today. He emphasized the importance of trusting the language. He helped me develop an understanding of how to take words on the page and bring them life, spoken by a real human being in a real world. Everything follows that.

I became a company member at the NEC in 1979 and performed in the original casts of Zooman and the Sign and A Soldier’s Play, which was a huge hit, running for more than 1,400 performances in New York and 26 months on tour. After a few months, the cast had started making what Doug called “improvements.” One night he came to see the show again and told stage management he had notes for us. We assembled in the small, narrow hallway outside the dressing rooms at Theatre Four. And one by one, Doug told us to take out the “improvements.”

One of the proudest days of my life was the day Doug said to me, “You are one of my actors now.”

The last time I saw Doug was in August 2019. Ruben Santiago-Hudson and I were rehearsing the Broadway tour of Jitney in New York. We invited him to dinner. We laughed and talked about old times, A Soldier’s Play, all the colleagues who had passed on. Toward the end of the evening he told us he had completed his magnum opus, decades in the making: The Haitian Chronicles. He told us it was at the printers. While he had been diminished by illness, he was the same old Doug: sharp, witty, still looking to the future and creating new theatre.

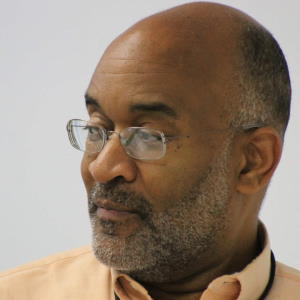

Steven Anthony Jones, actor

A Space of Liberation

I grew up in a theatre world of Douglas Turner Ward’s creation. As a high school student in Detroit, I marveled at the Bonstelle Theatre production of Day of Absence. I was too young to understand that I was witnessing revolutionary, incendiary Black theatre. I took it as a matter of course that Black playwrights and actors could put forth a vision of life in which whiteness would be treated as a joke, not as a malevolent force of destruction and death. Doug’s brilliance as a playwright shone through in this powerful piece de resistance. Later, in college, I experienced Joseph Walker’s The River Niger, which had originated at NEC prior to its Broadway run. Again, I was mesmerized by the message, the players, and the writing—all reflective of Douglas’s notion of the stage as a space of liberation.

When I learned about Doug Turner Ward’s New York Times editorial, which triggered the Ford Foundation grant that brought the NEC to life, I understood that he was not only a gifted writer but a visionary as well. Doug knew that training generations of actors, designers, playwrights, and administrators would do more to empower Black theatre than erecting a playhouse—so that’s exactly what he set about doing.

In 1976 I moved to New York City to pursue a career in the theatre. I landed at Woodie King Jr.’s New Federal Theatre, and Clinton Turner Davis was the first director I worked with. Since that time, I have shared the stage with such other distinguished NEC alumni as Yvonne Warden, Esther Rolle, Ethel Ayler, and Arthur French, to name just a few. Douglas Turner Ward created a unique space in American theatre. We are all his progeny, and we are still “studyin’ him” and signifyin’ and learning from his life.

Michael Dinwiddie, actor

How I Learned What I Learned

I started at NEC as an intern in 1980. My first assignment was to clean out the box office at Theatre Four. The Boys in the Band had been the last show there. It was located on West 55th Street between 9th and 10th Avenues. The Hare Krishna were located up on West 55th Street, and Hell’s Kitchen was a gritty, dark place to hang out when you finished rehearsal at 7 p.m. The Irish bar Amy’s ran a tab for company members and had hamburger deluxe platter that included a tomato and lettuce side that fulfilled your veggie requirements for the day. All was right with the world.

The NEC in the 1980s provided a venue for many young and not-so-young Black artists to work. The neophytes had an up-close opportunity to mix with the Frances Fosters, Rosalind Cashes, Graham Browns, Aldoph Ceasars. The Theatre Four administrative model represented the company’s ability to run a show (283 seats) and meet payroll on 80 percent capacity. This was a goal of Douglas Turner Ward and his journey toward autonomy for the NEC.

During this time, I was in graduate school at Columbia studying theatre management and directing. But the most significant instruction I received was as box office manager at Theatre Four, and alternately standing in the back of the theatre watching Douglas Turner Ward direct plays. I was privy to the lobby conversations between playwrights and director—not to be held in front of the cast inside the theatre, but box office staff was invisible.

Though I have paid off my graduate school loans to Columbia University, I will never be able to clear the debt I owe the NEC and Douglas Turner Ward for the invaluable experience I received!

Susan Watson Turner, theatremaker and professor

Finding the Play

As an undergrad in Texas in the early 1970s, I learned about the Negro Ensemble Company and sent a handwritten letter to them inquiring about their training and classes. I was inspired by what I learned they were doing and felt that was a place I’d like to be. I first met Douglas Turner Ward in Texas in 1977 or so at SMU in Dallas; I was invited to participate when Doug was a guest director and worked with students in the theatre department on The River Niger. Fast forward three years: I made my way to New York and made the rounds auditioning as an actor.

As an undergrad in Texas in the early 1970s, I learned about the Negro Ensemble Company and sent a handwritten letter to them inquiring about their training and classes. I was inspired by what I learned they were doing and felt that was a place I’d like to be. I first met Douglas Turner Ward in Texas in 1977 or so at SMU in Dallas; I was invited to participate when Doug was a guest director and worked with students in the theatre department on The River Niger. Fast forward three years: I made my way to New York and made the rounds auditioning as an actor.

I got an audition with Doug for Zooman and the Sign by Charles Fuller. Doug remembered me from Texas. He didn’t cast me in that play, but a year or so later he called me in for an audition for the Southern tour of Home by Samm-Art Williams to understudy Sam Jackson in the lead role. Got that job, on the road, bus and truck all through the South. It was great. L. Scott Caldwell and Carol Maillard and Juanita Jennings filled out the cast. We got back to New York and the next call from Doug was an offer to do A Soldier’s Play by Charles Fuller. That play won the Pulitzer Prize and ran for about two seasons at NEC and became their biggest box office success. It was truly a red-letter day for me when one day in rehearsals for A Soldier’s Play, stage manager Clinton Turner Davis walked up and handed me the handwritten letter I had sent to the NEC when I was in college.

I went on to work in almost every play done by the NEC for the next two seasons, almost in rep, performing one play eight shows a week and rehearsing the next play during the day. Manhattan Made Me by Gus Edwards, Nightline and The Redeemer by Douglas Turner Ward, Sons and Fathers of Sons by Ray Aranha, Prince and Sally by Charles Fuller, Eyes of the American by Samm-Art Williams. Doug challenged everyone every step on that part of our journey. It gave me a standard of excellence and a work ethic that has served me and so many others quite well over the years. We also have a special pride in the work we were doing: documenting the African American experience with our art, in stories by, for, and about Black people, with an ensemble of gifted artists. Black writers, directors, stage managers, designers, administrators, box office, company managers, even the ushers came together to tell tales and celebrate ourselves.

The NEC only did new plays. We were—I jokingly say sometimes—snatching these plays off playwrights’ typewriters and standing them up for the first time and learning from Doug about that process that I call “finding a play,” eight hours a day, six days a week. That practice was the most significant to my development as a confident, complete artist, and led me to sit down and try my hand at storytelling as a playwright myself. Doug read every play I’ve written and always sat with me with his thoughts and reactions and encouragement. And I’m proud to say plays by Eugene Lee have been met with critical and box-office success in America and abroad.

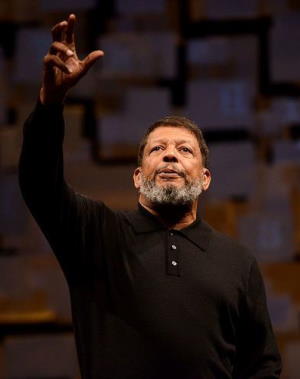

Eugene Lee, actor and playwright

The Most Important Event

I remember Doug over the years—we crossed each paths many times. I always held him in awe. We would greet each other, but as I recall we never talked then. When NEC was forming, I knew about it but I did not have the guts to approach him about it. Instead he approached me! I was able to audition for the company and was accepted as a founding member of the company.

That formation was the most important event that had ever happened for Black theatre in history! Doug’s vision, and his success in obtaining that Ford Foundation grant, made it possible for the founding members and 13 founding performers to be involved in something more important than anything before in Black theatre history. The superlatives, and all the respect and honors bestowed upon him, and the praise that has been heaped upon him, will continue into perpetuity. What happened in those three years could never be duplicated and was never duplicated. Performers in succeeding years got what they got because they passed through his hands!

Norman Bush, actor and photographer

Golden Years

Douglas Turner Ward—the best times!

I believe he was far more aware of my range than I could have imagined. Doug saw into me, to dare yet be aware. Speaking candidly, as the years have flown by, craft has been developed, and craft doesn’t mean “I know.” It means, “I know what my instrument needs, acting or directing, and where to go to get it.”

I treasure his vision and insight. From Leslie Lee’s The First Breeze of Summer, which was moved to Broadway’s Palace Theater, to Waiting for Mongo by Silas Jones, Eden and Nevis Mountain Dew by Steve Carter, Companions of the Fire by Ali Wadud, La Grima del Diablo by Dan Owens, A Season to Unravel by Alexis Devoe, Daughters of the Mock by Judi Ann Mason, Old Phantoms by Gus Edwards, to The Great MacDaddy and the Abercrombie Apocalypse by Paul Carter Harrison, and The African Plays, all interspersed with other theatre productions regionally, commercially, and internationally.

The time spent at the Negro Ensemble Company with Doug, company management, his choice of plays, designers, directors, stage managers, tech crews, and let’s not forget my fellow actors, was golden!

Barbara Montgomery, actor

The Founding Generation

My theatrical destiny with the Negro Ensemble Company began with newspapers. First, a lengthy article by actor/playwright Douglas Turner Ward in a Sunday New York Times had him speak about the lack of job opportunities for Black people in the theatre. His solution: the creation and establishment of a professional Black theatre company, “not out of negative need, but positive potential.” Back in my native Houston weeks later, I happened across a local news announcement of the creation of a Black theatre company in New York City. I called the NYC phone number to arrange for an audition. A receptionist answered (who I later believed to be the actress Denise Nicholas). Flying in from Houston to the St. Marks Playhouse, I said my hellos to actor/fellow Tenn State alumnus Moses Gunn, followed by an introduction to the main man, Douglas Turner Ward. As Ward and I entered the darkened mainstage for the audition, I noticed his chain-smoking choreography—and that decided my audition approach. I would perform the laborer monologue from the play In White America, recounting the tale of an elderly, exhausted Black tenant farmer in Alabama, victimized by a while landowner. Ward sat high up in the corner of the theatre while I went to my single spotlit placement. I waited a long moment while I stared toward Ward’s position, searching for his metronomic cigarette stroking routine—and his eyes. This would be the moment. This was it! Finally, I caught it, and so I began.

Audition ended, I said my goodbyes, thank yous, then back to Houston. Weeks later, a call came in from the newly named Negro Ensemble Company. I had made the cut. The moment was mine! And so the founding membership began. The first all-crafts meeting was on Tuesday of the second week of September, 1967, but without me—I had wrap-up business in Houston. Days later, I arrived to company anticipation—and some disappointment. It seemed that my being from Texas had infused the gathering with the notion that a Black John Wayne personified was joining the company, complete with strapping stride, cowboy authority, boots, toy six guns, and a 10-gallon hat. And when I appeared, it was more like the Texas Mickey Rooney. I said, “Give me a break, partners!”

Moving on, the 13-member resident acting company assembled and introduced: Norman Bush, Rosalind Cash, David Downing, Judyann Johnson, Frances Foster, Arthur French, Moses Gunn, William “Bill” Jay, Denise Nicholas, Esther Rolle, Clarice Taylor, Hattie Winston, and myself. Ed Cambridge was the production stage manager, joined later by Jim Lucas. Peter Weiss’s anti-apartheid drama Song of the Lusitanian Bogey was our initial production, directed by Michael Schultz. Training workshops were established: acting/voice/vocal music/movement. Finally, on Jan. 2, 1968, the company premiered Bogey to universal acclaim as a more than worthy addition to the New York theatre scene. The season moved on to Summer of the 17th Doll, Kongi’s Harvest, and God Is a (Guess What?). Moses and Denise moved on, replaced at different times by Sam Blue Jr., Graham Brown, Damon Kenyatta, and Mari Toussaint, among others.

Also during the founding years, NEC sponsored the Monday Nite series, showcasing company members’ other talents. Roz and Hattie did their musical concerts; choreographer Louis Johnson staged his solo dance creation No Way Out; and I produced and directed two one-act plays in affiliation with playwright Lonnie Elder, coordinator of the Playwrights/Directors Unit, using cast members Sherman Hemsley and Phylicia (Allen) Rashad, among others. International travel followed, with the company performing Bogey and Guess What? as a guest troupe invited to London’s Royal Shakespeare Company. Controversy arose at a matinee performance of Bogey at the Aldwych Theatre when an all-white, apartheid-sympathetic audience protest halted the performance, unnerving some of us onstage. The night’s performance, however, went without incident. We later transferred to Rome for a successful run at the Premio Roma Festival, yielding a festival award for excellence.

Some time during our third season, it became clear that the founding company’s run was nearing an end, as economic constraints set in and individual careers were moving on. I look back and upon my founding membership with the Negro Ensemble Company’s resident acting company as a case of being a supremely lucky actor…and man. As I have said more than once, Douglas Turner Ward, Robert Hooks, and Gerald Krone gave the founding folk not only our careers, they gave us our lives as we all have come to know and live them. In time, theatrical history will list, note, and forever maintain NEC’s original resident acting company membership and the accompanying units as one of the great cultural institutions in American, African American, and Africana cultural history. At some later point, no doubt there will be others whose skills and crafts will enrich and extend the Company’s founding legacy, and that legacy will echo the final words of the NEC’s premiere presentation of Bogey: “And there shall be more. You will see them. Many already in the cities..forests…and mountains. Laying in their weapons and planning with care…the liberation which is near.”

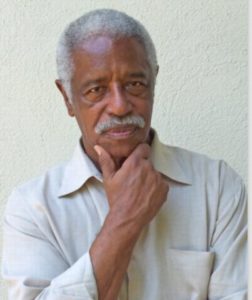

Allie Woods Jr., actor and playwright

‘I Knew That My Life Had Changed’

Mr. Ward is the reason that I’m where I am in theatre. Because when he offered me the opportunity to join the Negro Ensemble Company, I had three years of work, steady work, which actors don’t always get. My life was kind of changed; I learned a lot.

When we had the first meeting, I came during my lunch hour. And after he gave me all the information and asked me if I had any questions, I said no. He said, “Well, take some time before you give me an answer.” I said, “I’m in.” And he said, “Well, no, give it some more time.” So I waited another maybe four or five seconds, and then I told him again. When I left that office, I knew that my life had changed. I knew that this was the best thing that could happen. And I was not going to miss the opportunity.

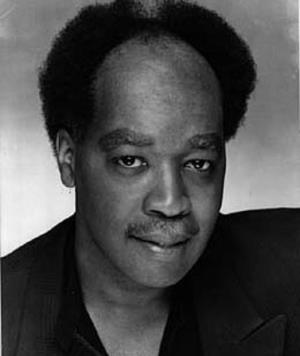

Arthur French, actor

Excellence…and Funding

The San Diego sunlight glimmered brightly on a mid-June day as the two of us gawked like star-struck teenagers as we gazed on his still imposing frame. She and I listened intently to his every word hoping to hear an inspirational nugget or two. We also had our cell phone cameras at the ready in hopes of securing a photograph for posterity, to someday share with our grandchildren.

Throughout this 2014 National Conference for the Theater Communications Group, the expansive legacy of excellence of Douglas Turner Ward as brilliant producer-director-actor-playwright-activist during the 1970s and ’80s filled the entire ballroom, if not the entire conference.

Meanwhile, the pair of star-struck individuals were representatives of the next generation of theatre artists: she, Sarah Bellamy, in line to inherit the baton from her father as the artistic director of Penumbra Theater, and me, former student of Hal Scott and Avery Brooks who was artistic leader of the Tony-winning Crossroads Theatre Company.

During our enlightened exchange, Mr. Ward boldly declared: “The Negro Ensemble Company had nearly a 20-year run of theatrical excellence that is unmatched. No theatre even comes close.” A quick check of the record book reveals this truth; from NEC’s inception in 1966 to the mid-’80s, this ensemble of Black artists and administrators garnered multiple awards and nominations: Tonys, Obies, Pulitzer, Drama Desks, and Critics Circles, to name a few.

What do you believe caused that? I asked. “Excellence, young man. We did not accept anything less than excellence. Oh, and funding.”

Yes, funding. After leading a culturally specific theatre for nearly 13 years, I am very familiar with the challenges regarding funding, as our field is entrenched with philanthropic systems that incredibly favor predominantly white theatre institutions.

But back to Mr. Ward and excellence: It is no secret that several NEC alumni from the early years have subsequently gone on to illustrious careers as Hollywood celebrities. That pathway never interested Mr. Ward. Indeed, by remaining true to the tenets of live theatre in New York City, Mr. Ward’s vision captured the imagination of and inspired many younger theatre artists who came of age during the company’s prime years.

For example, in 1978, a little more than a decade in existence, a pair of newly graduated theatre students from Rutgers University were inspired to start a Jersey embodiment of the NEC. Lee Richardson and Ricardo Khan embraced the NEC’s mantra of excellence. “We definitely aspired to maintain a similar level of excellence when we started Crossroads,” says Khan. “Well-crafted scripts, solidly built sets, great customer service at the box office. All of their standards we embraced.”

Also, as a young theatre wannabe in high school, I vividly recall viewing Home at the St. Marks Playhouse in the Village, then proudly purchasing a ticket to see it again when it transferred to Broadway (and the ticket was like 20 bucks!). In addition, I recall being floored by the gripping and charismatic performance of Adolph Caesar in A Soldier’s Play, along with the lasting memory of a terrifying Giancarlo Esposito as a predatory criminal in Zooman and the Sign.

One can only ponder how many young artists were inspired by the NEC’s nearly 20-year run of unmatched theatrical excellence—probably hundreds if not thousands. I know I certainly was.

Thank you, Mr. Ward, along with Mr. Robert Hooks, for your prescient vision that inspired an entire generation of theatre artists.

Marshall Jones III, director and theatre professor