The following is an excerpt from playwright Jen Silverman‘s new novel, We Play Ourselves. It tells the story of Cass, a playwright who deals with a career blow in New York by retreating to Los Angeles, where she grows entangled with a pack of feral teen girls and a documentary filmmaker.

The night that my play opened, my parents came in to New York. I could count on one hand the number of times they’d seen my work; they both hated cities, and theatre left them baffled. My parents had never told me to get a real job, but I knew that they thought of writing as a hobby, and that they were patiently waiting for me to become a teacher.

The last time they had seen one of my plays was when I was 25. I and three other writers had rented out the back room of a bar that came with a small square stage. We put on a night of one-acts, for which we were not only the writers but also the designers, publicists, ticket-takers, ushers, and cleanup crew. My parents had sat on punishingly uncomfortable plastic chairs, hands clasped in their laps, as the 10 other audience members around them shifted and snored. I don’t remember what my play was about now, only that my father fell asleep too, and my mother kept jabbing his thigh with her knuckle to try to wake him up before I noticed. We never talked about it afterward, and I hadn’t asked them to come see my work again. Not until now. And even now, in the days leading up to opening, I found myself having recurring nightmares that the theatre was empty except for my parents and Hélène, and as my play inexorably unfurled, all three were dozing.

On opening night, I got to the theatre 40 minutes early, poised to have a nervous breakdown. The lobby was already filling up, and Hélène was sitting to the side, long legs sprawled out. When she saw me, she smiled and stood decisively, motioning to me to follow her. Even before I’d reached her, she was already striding toward the doors to the theatre where two ushers stood on either side like stern guards. The house was not yet open. Hélène gave them a nod and we slipped inside.

“Hélène, what are we . . . ?”

Hélène put a finger over her lips and I smiled back, giving myself over to whatever she was doing. In the last two weeks of previews, we had achieved a careful balance. We’d watched the audiences watch the show, discussed and implemented notes. We never talked about Liz aside from her performance, and when Hélène said she was going to give Liz notes, I never argued with them.

From within the theatre, the murmur of the lobby was muffled and distant. Hélène produced a small stick of wood and a lighter, with only a glance over her shoulder—stage management would not approve—and held the flame to the end of the stick. Palo Santo, I realized, as the thin, sweet smoke spiraled up and dissipated. Hélène closed her eyes. I felt something go quieter inside me—not calm, exactly; oxygen reaching deeper places in me as I breathed. Hélène was reminding me, without speaking, that this space was ours—remained ours, no matter who came here tonight, audience or critics. That we were connected to a long and ancient lineage of players, that prayers for success were part of this lineage.

Hélène’s lips weren’t moving, but she was concentrating hard in a way I knew well. I closed my eyes too. I was silently repeating, “Oh God, let this go well,” again and again, but it didn’t feel like a prayer, because whenever I said, “Oh God,” I imagined The New York Times. After a time, I opened my eyes, and Hélène opened hers and smiled at me. She crushed the smoking end of the stick on the side of her boot, waved her hands in the air until there was no sign of smoke, and we both slipped back out into the lobby. The crowd had thickened in the short time we were inside the theatre. People were picking up tickets and finishing overpriced drinks and asking each other to hold their bags while they ran to the bathroom.

I fetched my four tickets from the stage manager, and Nico arrived moments later, wearing the powder-blue suit jacket I’d borrowed for the Lansings. My parents were right behind him. My mom was wearing black slacks and a sweater vest, and my dad had on his teaching uniform of khaki trousers and a worn blazer. I remembered those exact costumes from PTA meetings of my childhood. My parents seemed out of place in the crowd and a little awed by it; as I hugged my father hello, my mother pointed to the poster for my play and said, too loudly, “Cassie! It has your name on it!”

I felt immediately embarrassed, and also thrilled at having managed to impress her. “I know,” I said, trying for casual, but my mother knew me too well, and her sharp eyes found mine. “It has your name,” she said again, as if the first time had been for her but the second one was for me. Something lifted in my chest suddenly, a great balloon of feeling. I was so scared that it would translate itself into tears that I ushered them very abruptly into the theatre, telling them it was time to sit down.

As I joined Nico in the back row, I saw Hélène. She was in the same row but at the far end, sitting with a man her age. For a moment I felt an ugly spark of jealousy, and then I shoved it down.

Listen, I told myself. There will be this play and the next play and the play after that, and we’ll keep doing this—this part, the one we can do, where we make something that is unique to the two of us: two separate strands of DNA swapping around, intertangling, creating life. This hope settled into me like heat, and the audience settled around us, quieting into watchfulness as the houselights dropped low. Nico gave my knee a swift knock with his, a good-luck knock, and as I strained to make out Hélène’s jawline in the dark I thought: If this is all I get, this can be everything.

❦

It’s hard to remember how it felt to watch my play. Not because the memory is blurred—on the contrary, it seems to get sharper with time—but because the memory of unguarded joy is so keenly humiliating in the aftermath.

But if I have to tell you one thing, I can tell you that Hélène and I were good together. That the thing we made was a knitting of all of our best parts, all of our sharpest instincts, all of our daring. That we made each other more daring. That it was, to me, beautiful. That it was somewhere I couldn’t have gotten by myself. That it was where I most needed to go. That if I could get back there, even knowing everything that followed, even briefly, I still would.

❦

The opening night party was at West Bank. The roar of voices hit me even before I opened the heavy outer door. Inside, bodies were packed into the corridor by the bar, and a step-and-repeat was set up on the opposite side of the room. In the dining area, people moved in and among the tables, a buffet set up at the end with hot plates, pasta, chicken. Nico made a beeline for the buffet and was swallowed by the crowd. I fought my way to the narrowest corner, between the coat closet and the edge of the bar. Marisa materialized to give me a swift hard hug. She told me that the play was “new and raw and a voice from the future” but also at the same time “the voice of the now,” and that she thought a lot of theatres were going to be very excited about me.

“How was Hélène?” she asked. “Good match?”

“The best,” I said with a fervency that might have given me away, but Marisa was already looking over my shoulder toward a stately gentleman in the buffet line. “Oh, I need to talk to him,” she said abruptly. “We’ve been trading calls.” And she released me and slid back into the frenzy.

My parents looked out of place in the seething din, huddled close to each other, wincing whenever someone nearby shouted too loudly. I waved to them and we fought our way toward each other. “More of an audience than that one-act, huh,” I said when I reached them. I’d meant it as a joke, but the second I said it, I heard in my own voice how much I wanted them to be impressed.

“It’s great, Cassie,” my father said. “Your mother and I enjoyed it very much.”

I didn’t want to turn to my mother, but I immediately turned to my mother. My mother didn’t say anything; she put her arms around me and then held on, longer than I’d expected her to. I could sense her pride and her relief, like an electrical current traveling from her body to mine. I knew that she had been worried about me, that she had thought I was wasting years in which I could have been establishing a real profession. I felt that now, for the first time, my life here seemed real to her. That she looked at me and saw success. And this feeling was more of a victory than anything she could have said.

My parents left the party soon after that, and in their absence, I scanned the room for Hélène. Part of me had wanted to introduce them to her, and the rest of me had felt that convergence of worlds to be too dangerous. As I turned, my eyes landed on Liz. She was in a green silk gown, her neck and shoulders bare, her blond hair piled up on her head. Her collarbones shone in the light. She looked like one of her own pictures in the magazines where she often appeared. I so rarely thought of Liz as a celebrity—I mostly thought of her as Liz, and three layers underneath that (although I could only admit it when drunk), as “not-Hélène”—that this image of her gave me pause.

Liz was holding a flute of champagne, laughing at something someone was saying. She lifted her eyes to meet mine across the room and a spark passed between us. She lifted her champagne glass in a toast, and I lifted my wineglass back to her. Just then, a woman came up behind her and put an arm around her waist, and I realized with the shock of surprise that she’d brought her wife to the opening. I’d almost forgotten that she had one.

Her wife was older—in her forties, maybe—and she looked very impressive. She was wearing a stylish but shabby blazer with elbow patches, and serious spectacles perched on her patrician nose. Her hair was cut short and sprinkled with salt and pepper. I didn’t know exactly what she did, but she was clearly a Literary Lesbian. Had Liz said that she was on a book tour? Maybe I’d made that up from the fact that she was gone so much. There were stacks of heavyweight books all over their apartment—I’d seen them when I was padding barefoot between their bed and the shower. I tried to imagine what they talked about together.

Did Liz talk? I wondered if her wife had Liz read her drafts, if Liz lay on their bed in an off-the-shoulder negligee, surrounded by papers, and said things like But, darling, did you mean to use a metonym? Suddenly, in my head, Liz had a light French accent. I shook it away, drained my wine, gestured to the bartender for another.

Liz and her wife were moving toward me through the crowd. I glanced down at the bar in case Liz needed me to not see her, but when they got close enough, I heard her calling my name over the din. “Cass! Hey, Cass!”

She introduced me to her wife, all of us shouting. I didn’t catch her wife’s name. “This is the playwright,” Liz yelled, and the wife leaned in to congratulate me: “Happy opening.”

“Thank you!” I yelled back. She was much taller than I was, even in her leather loafers.

“I enjoyed your play,” she continued. “It’s a real deconstruction of desire.”

“It is?”

She lifted an eyebrow at me: “Isn’t it?”

I hesitated, not sure if this was friendly banter between intellectuals or if she was saying: It has come to my attention that you have fucked my wife on multiple occasions.

I looked to Liz for guidance, but Liz was looking at a reflection of herself in the mirror over the bar. She seemed unconcerned with us both. She adjusted a free curl of hair—tugged it looser, as if a very small and specific wind had swept into the bar.

“Desire both homosexual and homosocial,” the wife hastened to clarify. “You’ve used a facile form, of course—absurdism often feels flippant to me, personally—but it’s clearly intentional. Your engagement, I mean, with the form.”

Was she calling me lowbrow? I didn’t know what she was saying about the play, and I couldn’t decipher what she was saying about me and Liz under that. It was giving me a headache—that and all the yelling. Even more people had arrived, and now, every time someone new came in the door, the people around us would push into us. Liz was leaning over the bar flagging down a gin and tonic, and when the crowd

backed into her, she would ram the nearest offender with her ass cheek, swiftly and vengefully. Then the offender would ricochet off her and collide with whoever was behind them, who then absorbed the impact and shuffled and muttered, “Sorry.” The whole bar was full of people shuffling and muttering Sorry, and the wife had somehow fixed me with a quizzical and penetrating stare, as if we were in a place where answers were possible.

I gestured to the elbow patches of her jacket. “Those are so great,” I said. “Did you do them yourself?”

Liz returned to us at that moment, clutching her G & T, and moved us into safer territory: “Baby, Cass won a big award with this play. It’s so exciting to see somebody’s career launch like this.”

“Yes, very exciting,” said the wife. “Congratulations.”

“You too,” I said automatically, and then it was awkward. “I mean. Liz is amazing in the play. We’ve been so lucky to have her.”

“It’s been a great opportunity for her to do something other than TV,” said the wife.

“TV has gotten much smarter, honey,” Liz said quietly to her wife. “Maybe if you watched it, you’d enjoy it.”

“I’m sure that’s the case,” the wife said in a voice that was sure of the opposite.

A look of pure hurt crossed Liz’s face and then smoothed over quickly. It made her look like a kid: Liz in grade school briefly staring out at us from underneath the hair and the collarbones and the career. I felt like I’d just seen Liz more purely and truly than either the Liz in my bed or the Liz in my play.

I was suddenly depressed for her. I imagined all her red carpets, her Emmys, her photoshoots, and her wife’s voice in her head the whole time, saying dryly: I’m sure that’s the case. I gave them both a polite smile and made a muffled excuse about saying hello to somebody somewhere. I pushed off into the crowd, letting it carry me. An assortment of shoulders and hips and elbows bore me along, and I let myself go beautifully limp in the middle of it. I was subject to the room, without desire, without destination. I was a cell in the middle of a frenetic and vibrating body of cells. I had cell mind, which is to say, I was blank. Anything could be.

And it was from that place, receptive and quiescent, that I felt a shift: one tide going out and another coming in. A hush entered the room like a new wind, living underneath the chatter of conversation. People were unobtrusively glancing at their phones while their conversations forged onward absentmindedly without them. At first I couldn’t understand it. And then I realized: The review was out.

An engine kicked on inside me. I motored through the tangle of shoulders and arms toward the women’s restroom. A waiter passed me with a tray, which I dodged by centimeters. Once inside, I slipped into a stall and locked the door. My breathing filled the sudden silence. The stall was like a small room, the walls and door going all the way to the ground, the floor tiled in clean white. The quiet was astounding after so much noise. I took out my phone, brought up the review, and read the whole thing.

It was dismissive and cool and eviscerating. It questioned the right of the play to exist, and beyond that, my right to have made it. It was bewildered by the disparity between the promise I had exhibited and the failure I’d delivered. Where was my treatise on coming of age, or female sexual awakening? Where was the “fresh and uncompromising” voice that everyone had been promised? This was weird. It was ridiculous. It was European, and not in a good way. How had anyone consented to produce it? It was a travesty that a TV star such as Liz had deigned to do theatre for the first time and been cast in something like this. Why wasn’t she playing Ophelia at the Public? Frankly, the whole thing was more than disappointing—it was offensive. There were serious people who had serious things to say. I, clearly, was not among them.

After I finished reading, I sat on the bathroom floor for a long time. It took time to catch up to what I’d read, and then to realize that it applied to me, to my play. That everyone outside was currently reading it and knowing that it applied to me and my play. There was a surprising chasm between the world I had been in before the review came out and the world that I was in now. From the previous side of this chasm, I had projected into the future. I had seen the opening night party, the celebration, the triumphant hug between myself and Hélène. I had seen the moment in which I paid for a cab, profligate with victory, and went home and slept the sleep of the righteous. I had foreseen the moment in which I awoke to congratulatory emails and texts and offers for more productions, opportunities to go to Helene and say, Let’s do it again. To say, underneath that, I have something to offer you.

A great flashflood had appeared from nowhere and washed it all away. The bridge between where I was and where I could see myself being was gone. I sat on the bathroom floor, stunned. Nobody had told me what to do if this happened. Nobody had told me this could happen. Nobody had told me what comes next.

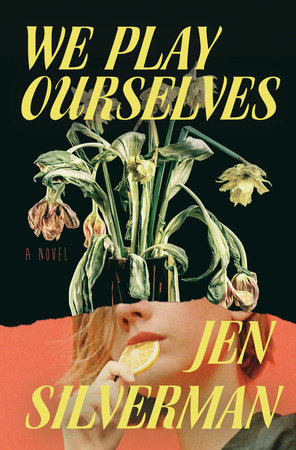

Jen Silverman (she/her) wrote the plays The Moors, Collective Rage: A Play in Five Boops, Witch, and The Roommate. She is a two-time MacDowell Fellow, and is the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts grant and the Yale Drama Series prize.