Over the last 12 months, theatre artists have been organizing with renewed vigor toward dismantling the white supremacist structures we’ve inherited, which pervade much of the regional and commercial theatre system. However, most of the highly profiled organizing has taken the shape of critiquing predominantly white institutions. Little of it has actively focused on building the world we want to see. (Let us be clear: We know that there are plenty of arts workers modeling the way, but national attention has been focused almost exclusively on organizing that centers whiteness and predominantly white institutions.)

One of the principles of Emergent Strategy, a movement tool that we frequently return to, is “what you pay attention to grows.” That is to say: Where you choose to invest or divest your energy, your time, your labor, and your resources matters. Not only is it an important political act, it’s a proven scientific phenomenon that what happens at the small scale also happens at a large scale. The ramifications of our actions, like fractals, echo out to inform the larger system. So if we choose to center our attention on whiteness, the power of whiteness grows. This is not what we want. How can we seed the growth of something else? We propose that, alongside critiques of what doesn’t work, we must focus our attention on laying a foundation for a just future.

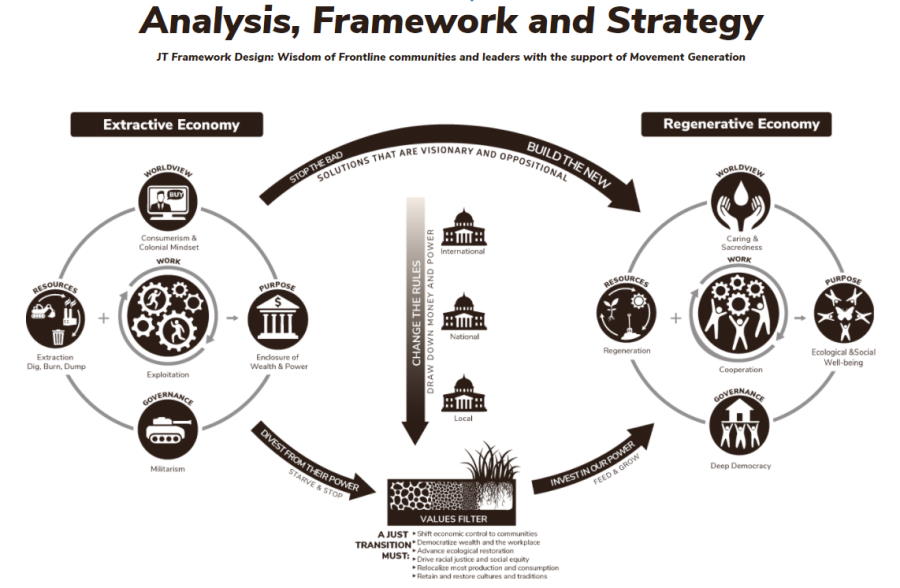

The program’s goals can be stated simply: Divest from the bad, invest in the good (and sign the pledge!). But there’s more to say about it, of course. We recently outlined an argument for theatre workers to divest from fossil fuels, and here we’d like to focus on the other side of that coin: investing in the systems, communities, dreams, and futures we long for. It is not enough just to divest from harmful systems; we must also invest in the new and generative. We have the opportunity to dismantle exploitative practices and, in their place, seed a just future.

What if…

In the not too distant future, a global Just Transition from extractive economies to regenerative economies has taken place, driven in part by arts workers and arts and cultural institutions divesting from fossil fuels and choosing instead to invest in regenerative ways of working. In this not too distant future, the incomprehensible magnitude of the global wealth gap has been dismantled through a wide scale redistribution of wealth and investment in local, bioregional economies. Large funding organizations have committed to spending down corpuses and made reparations to the communities they made their wealth on.

Because wealth has been redistributed, individuals can now invest in the art that is meaningful to themselves and their communities. Publicly transparent budgeting and participatory processes are the norm in the arts and in our civic governing practices. In fact, our local and global relationships to resources is now characterized by principles of regeneration rather than consumption and waste.

Theatre is able to meet the moment and create work that is accountable to the people around its workers. In this not too distant future, the global capitalist culture of disposability which relies on mass consumption and mass incarceration has been abolished. Inside of this shift, BIPOC artists and decolonized ways of working are the standard. Now theatre workers are working within systems where they can be their whole selves, where families can have the time they need, where rest can be had by all, and where theatremaking is regenerative and energizing rather than extractive and draining. Art making is in joyful relationship with communities, and artists and audiences are in right relationship to each other, the land, and their mutual histories. Sound familiar? Perhaps you’ve heard us talk about it in the Green New Theatre.

So how do we get here? We get to this future by investing in the well-being of frontline communities and frontline arts workers. (Frontline communities are those who experience the “first and worst” impacts of the climate crisis. They are Indigenous and Black communities, low-income communities, coastal communities of color, migrant workers, and more.) As the Combahee River Collective articulated in the 1970s, “We realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy.” Black women have told us for decades: When Black women are free, we’re all free.

This logic follows in responding to the environmental racism of the climate crisis: when we prioritize the safety, well-being, and freedom of frontline communities, we are all safe, well, and free. The Climate Justice Alliance and others have said this: Reinvesting in community power is a key strategy in the global Just Transition.

So then the question is…

What actionable steps can we take now toward investing in that future where we’re all safe, healthy, and free? We suggest a three-pronged approach, which interrogates: 1. Where we invest our material resources, 2. Where we invest our finances and endowments, and 3. Who is investing in us. Think of “investment” as attention. Remember: What you pay attention to grows.

What future are you currently growing with your investment of attention, time, care, and finances?

Where We Invest Our Material and Liquid (Cash) Resources

Actions related to divesting and investing do not merely relate to the realm of finances and the market, though we’ll get to that in a moment. For now, we challenge you to dig deeper. Consider all your resources at hand. Is it space? Is it time? How can we reorient ourselves away from capitalist extraction and into relational ways of working and being together?

Theatres:

- Invest resources (productions, residencies, long-term developmental support, office space, etc.) in BIPOC artists and especially in BIPOC artists with decolonized ways of working/creating. What if we invested in people rather than products?

- Consider setting up policies to give a percentage of your income to frontline organizations in your communities. For example, at Groundwater Arts, as standard practice we invest 3 percent of all of our income in frontline organizations, which we identify on an annual basis. This year, we’re donating to Native American Lifelines of Baltimore, the NYC Environmental Justice Coalition, and the Terrence Crutcher Foundation in Tulsa.

Independent artists & producers: It’s tempting to think to ourselves, “I’m not in a position of power at an institution, so what agency do I really have?” We hear you. However, we all have more power than we tend to think, especially when we organize and work collectively.

- Producers: get involved with the Producer Hub to find values-driven colleagues.

- Artists: Who are your assistants? Who are you mentoring? Consider developing an inclusion rider for all your contracts.

Foundations & funders: It’s past time to decolonize philanthropy. While we (and brilliant thinkers such as Edgar Villanueva) actually believe you should make plans now to spend down your corpuses, in the meantime…

- Get real clear on the principles of regenerative finance.

- Invest your resources and relationships in theatres of color, collectives, and grassroots cooperatives working in socially responsible ways.

- Invest in BIPOC training programs and teachers.

- Invest in BIPOC careworkers, healers, and artists who may not define their practice in ways that are currently legible to you.

- Start instituting publicly transparent budgeting of your funding decisions.

All of us: As we are moving toward regenerative ways of being, we must also adopt regenerative practices for time. There are movements such as No More 10 Out of 12s and demands made by We See You White American Theatre to instill a five-day work week and call for the theatre to end the extractive time practices that disenfranchise BIPOC, disabled people, caregivers, and low-income folks.

If you’ve been part of any public-facing event with Groundwater, you’ve probably heard us talk about time. Tara Moses talks about time in relation to her Indigenous communities, where time is relative. More specifically, time is a relative. Time is a living entity whom we create meaningful relationships with, just as we do with our elders, our aunties, our grandmas, etc. If we take care of time like we take care of our elders, suddenly the immense pressure to extract every moment of productivity vanishes. Suddenly we prioritize care for one another—and for the clock on the wall. Before you know it, there isn’t the stress of getting through every scene scheduled that day for rehearsal, because we understand that time will take care of us in the process too.

We’re also advocating to be regenerative in our budgeting practices. Here’s some things we can all do right now:

- Publishing publicly accessible, detailed, itemized budgets: See Flux Theatre’s Open Book Model.

- Passing budgets with full agreement of both communities and employees: See Alternate Roots.

- Making major financial decisions in open meetings where decisions are made by vote.

- Check out the Green New Theatre for more!

Where We Invest Our Finances and Endowments

Beyond cash and non-monetary resources, for those of us (individuals and institutions) with money invested in various forms of the market, we can shape change by shifting how and where we invest. This can have an enormous impact if we do it collectively.

Theatres with endowments:

- Ask your investment committee to move money from fossil fuel funds to renewable energy projects and/or BIPOC-led businesses. Ask them to move to funds managed by BIPOC fund managers. Give them a timeline.

- Given the sometimes complex reality of stakeholder relationships, we suggest 1-2 years at maximum to have the conversations necessary to move the money.

Individuals and theatres:

- Where possible, move money from large-scale corporate banks to credit unions to keep money moving locally. Banks are some of the least transparent and highest sources of funding for all kinds of harmful practices in the world, not least of which are fossil fuels. Because of their locality and mission, credit unions are held to higher standards of community accountability and transparent practices. They also tend to invest more heavily into local small businesses.

Theatres organized as cooperatives:

- Check out the Working World and Seed Commons for opportunities to apply for community controlled non-extractive loans.

Foundations:

- Make a plan now to spend down your corpus. Yes, we do actually mean this. We suggest prioritizing giving the wealth back to communities from which it was initially extracted. Foundations only spend ~5 percent of their endowment each year, and most keep the other 95 percent invested in “the very companies creating the social and environmental problems foundations are trying to address.”

- In the meantime, as you make your spend-down plan, move your investments to socially responsible funds immediately. According to NPQ, “Only about one in five foundations are actively looking at their investment management practices.” Let’s make that five out of five asap.

All of us:

- Be sure to check your investment portfolio at FossilFreeFunds.org, where you can enter a ticker code and see a grade for the fossil fuel impact of your investments.

- Also, consider alternative models for investing. For example, we love the Industry Standard Group, which is creating a new pathway for BIPOC investing in commercial theatre projects.

Who Is Investing in Us

If it hasn’t become obvious already, money is a kind of relationship. It’s a flow of energy. It can accumulate and be used as a source of control, or it can circulate and be used as a source of regeneration/agency. This means that, especially for those of us operating in the nonprofit industrial complex, our flows of money are even more important, because we are accountable to the people and communities we serve. Where we spend our money is an expression of our values, just as where we accept money is a choice. All money is political.

Let’s be real: Funders and corporations don’t often give large sums of money to us just because they believe in art as public good. There are unspoken—and sometimes spoken—social benefits deeply tied up with large “gifts” and sponsorships. This permission is called a “social license to operate.” It allows harmful industries, like gas and oil, to be seen in a better light, because when they sponsor our shows and put their names in our programs and on our buildings, they are seen as gentle benefactors of something we all love and enjoy. Not only are they exploiting the planet, they’re exploiting us. We need to examine how our fundraising strategies reify white social control, and get excited about the possibility that by examining our gift policies, we could shift extractive industries’ social license to operate.

Theatres large enough to accept sponsorships and foundation support:

- Move away from foundations and corporations who have made their wealth in fossil fuels and extractive industries and move toward community-led, grassroots donors and funds.

- Look to place-based community controlled funds (Boston Ujima project and others) for examples in your own community.

- Ask your development officers to create a clear gift acceptance policy that is aligned with your stated values. Remember: Especially if you’re one of the theatres that recently made a statement about your support for antiracism, you need to be clear that your corporate sponsors are not harming BIPOC communities. We have an opportunity to use our public institutions to support regenerative institutions.

Individual artists and small theatres:

- Consider alternative economic models that don’t require money (ex: timebanking, credit clearing, bartering).

All of us:

- We need to reframe our concept of money and its purpose. If you haven’t read Lewis Hyde’s The Gift, we highly recommend it as a resource for rethinking the transactional nature of our current economy.

In Closing

There is a guiding theme that emerges when we take on this work: reciprocity. In a future shaped by reciprocity, our individual and institutional finances are invested in renewable energies and BIPOC-led projects. Reciprocity resists the accumulation of individual wealth and prestige, and instead requires interdependence. Reciprocity resists a culture of disposability. Instead, it requires recognition of the inherent dignity of all living beings.

In theatre and performance, a future characterized by reciprocity would mean that work created by and for dead white men is no longer systemically overrepresented and dominant. Instead, there would be room for all of us in the circle—with no one in the center.

As the theatre industry sets its sights on building back and reopening, we can make choices now to center justice, reciprocity, and healing. Movement-building for the world we want to see must embrace those who are already leaders in that new decolonized future. We need to stop gathering artistic directors around tables to solve our problems, and instead listen to those on the frontlines: BIPOC arts workers, organizers, and change-makers.

And we need to reach out our hands beyond the theatre. At Groundwater Arts, we do our best to move in alignment and right relationship with our friends at Movement Generation, Alternate Roots, No Dream Deferred, Another Gulf is Possible, Broadway for Racial Justice, and more. These are folks who have been building the road maps that will lead us from crisis to justice in the field of the arts field and, more importantly, beyond.

In a future characterized by reciprocity, we can let go of artistic economies driven by white supremacist ideas of individual prestige and “excellence.” These ideas are systems are driven by a scarcity mindset that centers fear-based competition. Instead, we will have a world that understands artistry as both gift and responsibility to community—a world of abundance, rooted in a mindset that centers interdependence. We believe that as we invest our attention, time, and resources in frontline communities, a new future will emerge. In the words of Arundhati Roy, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

Groundwater Arts is a predominantly POC, half Indigenous, fully women-led artist collaborative based across the United States. They are committed to reenvisioning the arts field through a climate justice lens, which is activated through the principles of a Green New Theatre (GNT), a movement-building document penned by Groundwater Arts in partnership with countless arts makers throughout the country. Collectively bringing decades of multifaceted expertise and artistic practice, their mission is to shape, steward, and seed a just future through creative practice, consultation, and community building.