By the middle of last summer, graduating virtually seemed to be the least of my worries. Being present was the hard part. I was living in a house with my cousins, aunts, and grandparents. “I can only imagine how tough this must be on actors,” my grandfather commiserated. As a working actor for over 10 years, and ready to hit the ground running post-graduation, I was stranded. As many of us were and still are.

By the middle of last summer, graduating virtually seemed to be the least of my worries. Being present was the hard part. I was living in a house with my cousins, aunts, and grandparents. “I can only imagine how tough this must be on actors,” my grandfather commiserated. As a working actor for over 10 years, and ready to hit the ground running post-graduation, I was stranded. As many of us were and still are.

Then I found Winnie. During my sophomore year at Princeton undergrad in the fall of 2017, I read Happy Days by Samuel Beckett for the first time in a modern drama seminar. Here was a miraculously optimistic woman, resilient and set on making each “day” meaningful, despite being buried up to her waist in earth. I put “day” in quotes, since every time the word is mentioned Winnie exclaims, “The old style!” She is stuck and alone, save for her husband, who resides in a hole behind her and goes days without responding to her. And so she seeks comfort from various things contained in a bag at her side. We watch her for an hour and a half simply find pleasure in thinking through her existence.

By that point in the summer, I was starved for work. The term “virtual theatre” started popping up in my circles. I thought it was time I take a stab at it. Beside the immediate relevance of a woman choosing to live with so much lost, Happy Days seemed a good fit for the form: It consists of only two roles on one set, and has minimal blocking. Rehearsing this virtually did not seem impossible. In addition, tackling Beckett seemed like a fantastic way to keep challenging myself as an actor while the industry remained barren. I reached out to a dear friend of mine and fellow Princeton alum, Nico Krell, whose work as a director on campus I admired greatly. It was time to join forces in the real world.

A true classic will always be relevant, and in this case, I feel it has never been a better time to explore Beckett’s Happy Days. While in a normal context, the play can be seen as a tragicomedy—a testament that life is bizarre in its suffering—now Winnie’s goal to remain positive and choose life, even when so many of its pleasures are stripped away, is a powerful force to witness.

Playing Winnie is a dream of mine. I am better for playing Winnie. She has an amazing practice of presence. It no longer serves her to dwell on how life was in the past, or wait for a future to come and change her situation in order to start living again. Rather, she decides: This is life. If this is the baseline, then okay. This is it. When Winnie first wakes up in the morning, she does not even reference her precarious situation. Instead she exclaims, “Begin Winnie! Begin your day, Winnie!”

In a time when many would posit that theatre is dead and awaiting its revival, Nico and I conceived a work with which we were able to process this time, as theatre always can. Winnie has taught us that to be alive is enough. Indeed, one of Beckett’s endeavors was to ask: How many theatrical elements can you strip away from a play and still call it theatre? Looked at in a similar light: How many things can be taken away from our daily lives and still call it living? I of course know that my life is privileged. I have a family that loves and supports me as an artist, and so on, but many of us are severely struggling with finding anything to look forward to, and that is just the problem. You cannot be living invested in a future yet to come. It does not exist. The only thing that exists is now, and Winnie shows us that that is plenty.

One of the reasons we are all grieving the loss of live performance is that theatre forces us to stay present in a way that is hard for many of us to recreate in other spheres of our lives. When we congregate for theatre, we focus solely on the other human lives life and we access their feelings together. I realized rehearsing this role that part of the reason I love acting (onstage especially) is how present I feel when I am in the moment.

Presence has also turned out to be my lifeline in this COVID era. It’s what’s ultimately kept me happy. I haven’t seen most of my best friends in over a year now, auditions are slow, there are many things I could worry about, but it just doesn’t matter, because my thoughts are only a fraction of the reality (I have Eckhart Tolle to thank for these discoveries). Much of “reality” is just what I am conscious of in my immediate surroundings.

Winnie ultimately realizes that: She need not work so hard filling her day with things to do. It is enough to just be and ask: What do I want to do in this moment? And now? She also realizes she is no happier or sadder now than she was when she had her legs. We tell ourselves it was better in the past, the future is brighter, but what about the only thing that truly exists: this very moment? How do we deal with that and appreciate that? If we have minimal access to pleasure, how do we practice gratitude for those blessings that are available to us in any given moment? Winnie marvels at the horizon and sun, squeals with delight when she sees a bug crawl by, reads the label on her toothbrush as if it were Fermat’s Last Theorem.

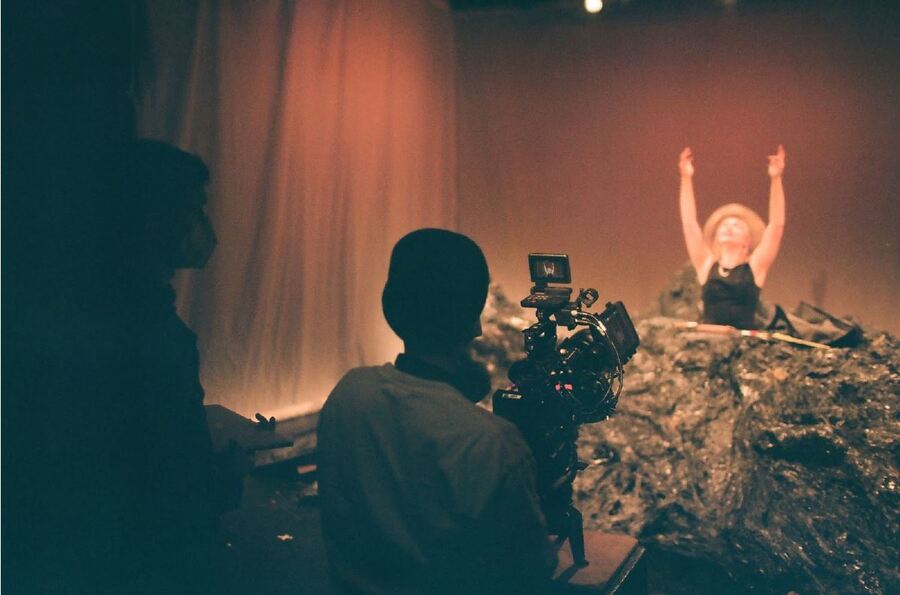

From the very beginning of our process, Nico and I were more interested in creating a visually engaging, beautiful spectacle than conveying “liveness,” since we both had grown wary of Zoom theatrics. After a two-month-long correspondence, Nico was able to obtain the rights from the Beckett estate. On principle, they do not allow filmed productions of Beckett’s plays. But Nico was able to argue that in such circumstances, this play’s message was more relevant than ever, and to perform to an empty house was conceptually sound. With the help of downtown theatre the Wild Project and Princeton University’s Fund for Irish Studies, we were able to produce a filmed theatre production of our Happy Days that will stream March 5-7 and March 11-13 on the platform Stellar.

Making theatre for no physical audience is a choice one must thoroughly interrogate and conceptualize. Fiona Shaw, who played Winnie in a production in the early 2000s, emphasized repeatedly in interviews how necessary an audience is to this play. However, it’s also incredibly Beckettian for Winnie to have no audience at all, at least not one physically with her. One of the main questions this first year of the pandemic has raised for me is: What does it mean to continue my work as an actor with no audience? Can I do it? The short answer is yes.

Similar to a tree falling in a forest, life and experience exist if you make it so. And so, from the first weeks of rehearsal, Nico instructed me that any lines that would traditionally be delivered to an audience, akin to stand-up comedy, I would just say to myself. I’m sure many of us are practiced at speaking in second person to ourselves since quarantine started. But the audience is not completely lost on Winnie or myself as the actor. After the opening segment of the play, Nico directs me to look directly into the camera with a knowing look to audiences at home, as if to say, “Thank you for coming,” and then immediately shake it off and say to myself, “On, Winnie.” For the rest of the show, save from a few lucid moments, I am alone and unaware of the camera, let alone an audience.

A recent discovery I had as an actor, especially in theatre, is that we are not tasked with being so “real” that the audience forgets we are all in a theatre. We are, however, tasked with creating a real feeling that the audience then gains access to through our work. Filming inside an empty theatre house, to empty seats, staring down the barrel of a camera, it rang true that these things will always be there: the feelings and the connections.

I do hope we will be able to return to this masterpiece at a later date with a live audience. Winnie so longs to hear you laugh again.

Tessa Albertson (she/her), who was seen on Broadway as Teen Fiona in Shrek the Musical, has been acting professionally since the age of 11. She graduated from Princeton University in 2020 with a BA in English and a minor in American studies and theatre.