“All of us, in some form or other, are touched by mental illness, either in our family, our friends, our neighbors, or ourselves,” said Elena Araoz (she/her), director of Manic Monologues, an upcoming virtual experience presented by the McCarter Theatre Center. Gathered from the experiences of those living with mental illness, Manic Monologues has journeyed from play to pandemic-postponed reading to virtual interactive experience. Its debut on Feb. 18 marks an effort to expand the conversation around the subject.

“If we continue, as individuals and as a community, to stigmatize it,” Araoz said, “to not talk about it, to hide it, to keep it a secret, then we are not only doing a disservice to us and our families, but also our entire community.”

That destigmatization is a key reason Zach Burton (he/him) and Elisa Hofmeister (she/her) embarked on Manic Monologues in the first place. The idea was born back in 2017 at Stanford University, when Burton, who was pursuing his Ph.D. at the time, experienced what he called an elevated manic episode. This psychotic break, Burton’s first, resulted in him being hospitalized and diagnosed as bipolar.

As he was going through this period with those close to him, including Hofmeister and his friends and family, they began to notice a seeming scarcity of hopeful stories in circulation about the experience of living with mental illness. It was all too easy instead to fall down the unsettling rabbit hole of Googling symptoms. Hence Manic Monologues, an effort by Burton, currently managing editor of a post-traumatic growth storytelling nonprofit, and Hofmeister, a medical school student who studied human biology at Stanford, to collect true stories from those living with mental illnesses, written as monologues and performed by actors.

Explained Hofmeister, “We decided on theatre in the beginning because we wanted to have a way to hold an audience captive and to really guide them through an experience of mental illness. We wanted there to be that connection of empathy that you really get from seeing someone perform on stage.”

The project began by gathering real stories from submissions from storytellers and open calls in Facebook advocacy groups. The expectation was that they’d receive stories mainly from their local community, but they wound up receiving a flood of stories from all over the country and beyond. Around 50 submissions were narrowed down to 20, with Burton and Hofmeister spreading the submissions out on their kitchen floor as they searched for the best way to capture a wide spectrum of stories, from hopeful and uplifting to sad and serious. This culminated in a production that had a few live performances in 2019 at Stanford—performances a McCarter board member just happened to attend.

That’s how McCarter resident producer Debbie Bisno (she/her) originally found out about the project. Bisno, who had her own personal passion for the subject matter, reached out to Burton and Hofmeister, and soon arranged a staged reading for Manic Monologues in Princeton, N.J., where the McCarter is located. Bisno partnered with Princeton Health Services for a panel discussion, and the McCarter was ready to start auditions for this one-night reading. Then the pandemic forced a postponement of the production.

As the pandemic lingered over last summer, conversations around the production eventually resumed. As it became clear that an in-person staged reading wasn’t going to happen, at least not for a while, a silver lining started to emerge. Perhaps this was a chance to make this project and its message, originally intended for an audience limited to those who could attend in-person, available more widely.

“We were all in a moment of political strife, racial reckoning, turmoil with the unknown,” Bisno said. “I mean, it’s always an important time and good time to talk about mental health, but it felt like this was even more of a zeitgeist moment in a way.”

Bisno then brought in Araoz, who leads Princeton’s Innovations in Socially Distant Performance at the Lewis Center for the Arts, to direct the project and create the concept for the virtual experience. Araoz said she wanted to find a way to tell these true stories in a way that was theatrical, but also humane and responsible. She wanted to find a way to help guide audiences in bringing mindfulness to watching, say, a mother struggling with her own mental illness while also being challenged by her relationship with a child. It was important, Araoz felt, to acknowledge what it means to watch, through the eyes of those with mental illnesses, aspects of life that might otherwise be considered mundane.

“What does that person have to go through just to struggle through on their own and take care of a dependent and cook themselves food?” Araoz mused. “These filmic recordings look at everyday life, and just how everyday life sometimes can be a struggle in and of itself.”

Monologues were filmed in each actor’s home, a pandemic requirement that actually lent itself well to the aesthetic of the production. But one big question still remained for Araoz: How can you make a group of individual pre-recorded monologues feel live?

“What is liveness?” Araoz wondered. “How is the audience still in that live conversation with what’s happening? I knew somehow that the experience needed to be interactive. I knew the audience needed to have agency and choice as they went through this journey. They would have a choice into how they saw the piece.”

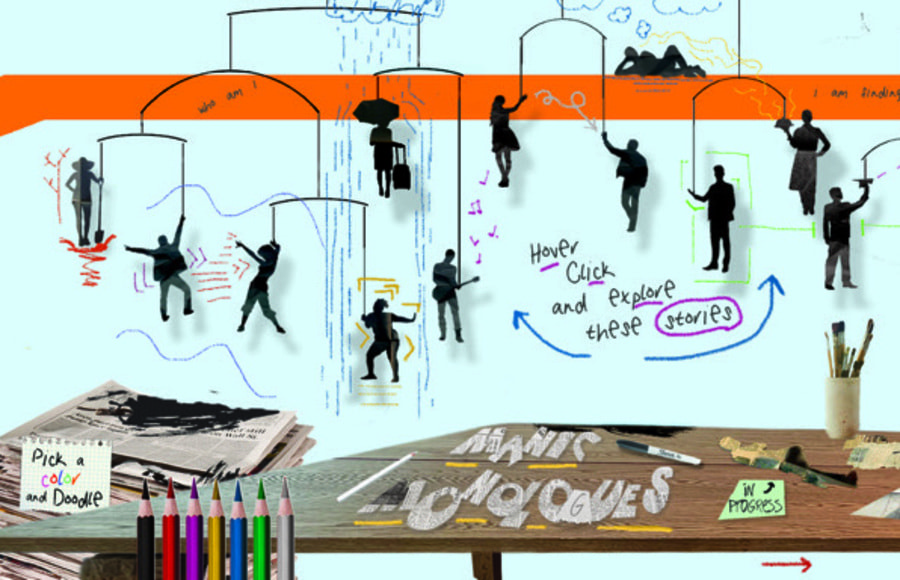

Araoz, along with multimedia designer Jared Mezzocchi, composer and sound designer Nathan Leigh, and web developer Jackie Liu, created an interactive website to house Manic Monologues. The website allows audiences to choose their own path through the monologues, which have been re-curated after the 2019 production to include some monologues that speak to the unique challenges of living with mental illness amid this pandemic and anti-racism movement. With no designated path through the production, each person’s story and monologue is represented on the website as a paper cutout hanging from a virtual mobile. After the monologues, there’s even the opportunity to see a brief postscript on where the real person the monologue is based on is now.

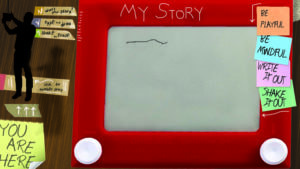

Beyond simply choosing which monologues to watch when, the production invites audiences to bring themselves to the experience. Virtual tools are provided to allow participants to doodle on the “walls” of the space to express reactions or feelings that come up in response to the monologues. There’s a virtual Etch A Sketch, providing a space to journal thoughts and erase them again with a simple shake. All of it harkens back to the desire to bring mindfulness to the experience, inviting each audience member to guide their own experience and pace the production as they see fit without being beholden to a specific narrative.

It should be added that the preview I was given of the website was not a finished product, with the design team deep into what can only be considered the equivalent of tech week when we spoke. As Mezzocchi mentioned to me, this has been a unique working experience for all involved, with all of the lead creative forces—Burton, Hofmeister, Araoz, Mezzocchi, Leigh, and Liu—coming from varying backgrounds and speaking slightly different creative and technical languages. That said, together they have created an interactive experience that cannot be easily replicated, with the order in which monologues are watched or the pace at which you click a button determining the intricate soundscape playing in the background.

“In this situation,” Araoz explained, “with the cues we’ve given—virtual visual cues, sonic cues, any content warnings—you get to plan your experience, you get to be a writer of the narrative of the journey, because depending on where you start, you’ll have a radically different idea or sociopolitical investment by the end than you would if you had chosen a different place to start.”

Importantly, this production, like the original staged reading, seeks to educate beyond the monologues themselves. The website includes a plethora of external resources and curated panel discussions. The hope is that the site can be more than just a theatre production at the end of the day—that it can also be a resource for community groups and schools to use to open discussions around mental illness while also still having a future life onstage with theatres as originally intended.

Bisno sees the production and the creative way it is being implemented online, a collaboration that also included working with the 24 Hour Plays, as one that opens doors moving forward. For the McCarter, that means seeing more ways (and more creative ways) to supplement in-person programming when the theatre eventually returns to the stage. But it also serves as a blueprint for the potential exploration of other stigmatized topics.

In the end, as Araoz noted, they want the Manic Monologues site to be a place where people can go for information. It’s an open invitation not only to listen to oft-overlooked stories but also to add your own. Nothing an audience member puts on the website is recorded; it’s not there to become a permanent addition to the production. Instead it’s an opportunity for honest reflection, more education, and open conversation.

“I’m excited for this to be a place where somebody goes and learns something about mental illness,” Araoz said. “We don’t really have a way of talking about it that is honest; we just have a lot of myths surrounding it or fear. You could actually learn something from these stories and from the huge amount of resources that we have. We hope that all kinds of people of all ages will come and learn something and be a part of the conversation.”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor at American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org