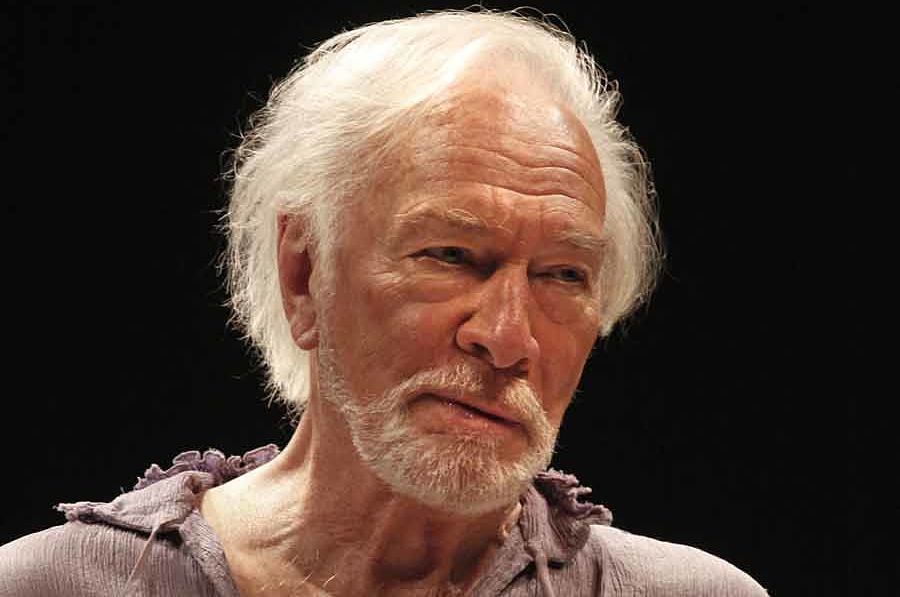

Christopher Plummer was not only one of the great actors of our time but the quintessential artist. He was a brilliant improvisational pianist and a magnificent writer. He had a great gift for elocution and a wondrous wit, and was a formidable raconteur. I remember watching him sketch in rehearsal one day, and, looking over his shoulder, beheld a genuine work of art coming to life.

He was more than just a celebrity; he was the equivalent of our royalty. As an actor, he had a breathtaking ability to make language soar, a great grasp of psychology, and a nifty tool which is often overlooked: He was an accomplished mimic. In the middle of a speech, suddenly the voice of Lionel Barrymore would appear. I once suggested a particular moment might have been played brilliantly by Alan Rickman, and the next thing I knew, it was as if Alan Rickman stood in front of me. Chris had the complete set of skills, and he was a master of all genres. We had been working on King Lear recently, and even at the end, he was overheard by his extraordinary wife Elaine quietly reciting his lines.

Chris didn’t go to drama school. He developed his craft the way the theatre has trained artists for centuries: through the ancient practice of apprenticeship. As a young actor, he did radio drama, sometimes daily, doing countless broadcasts of classic and contemporary drama, even the Bible. He performed in theatre companies in Ottawa and Montreal, even in exotic Bermuda and eventually Broadway, before finally taking his rightful place at the Stratford Festival of Canada while he was still in his 20s. There he played Hamlet, Henry V, Aguecheek, and Cyrano—many of the great classical roles. Stratford, Ontario would become his creative home for decades to come, and his mentors there included the legendary Tyrone Guthrie and artistic director Michael Langham. In England, he collaborated with Olivier and worked at the Royal Shakespeare Company and on Broadway with many of the great theatre artists of his time. He became the eternal student, and he worked tirelessly, researching and studying for each and every role he played. He learned to check that work at the rehearsal room door, though, so when he delved into a scene, he was largely free of accoutrements, spontaneous, absolutely in the moment.

Chris could be impish and wise, and most importantly, he had profound generosity, particularly toward other players. He not only loved acting, he loved actors, and he relished the gifts of the most brilliant ones. When he returned to the Festival stage in 2008 for the first time in several years in Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, one might have expected, as Stratford’s favorite son, that he would take the last bow. He insisted, however, that his Cleopatra, Nikki James—largely unknown at that time, as she had not yet won the Tony—share that final moment with him. During their performance together, it was not just about Caesar mentoring Cleopatra; Chris was speaking directly to Nikki. It was the kind of gift that a director longs for when you’re free to become as much of a passenger as a pilot.

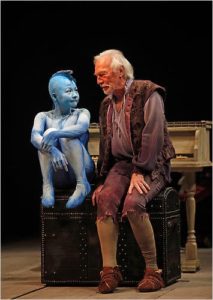

Chris understood the importance of partnership. Often the story takes place in the space between the points of view of the players. During 2010’s The Tempest, in which he played the titanic Prospero, at the beginning of Act V in the scene with Ariel (played by the breathtaking Julyana Soelistyo), the spirit says to him, “Your charm so strongly works ’em / That if you now beheld them, your affections / Would become tender.” We had agreed that we would stage this most simply with the two of them sitting on the forestage about 15 feet apart. Chris as Prospero asked quietly, “Does thou think so, spirit?” And Ariel turned to him to say, “Mine would, sir, were I human.” Chris had profound respect for the meter and the music of the text, but at this moment, he took advantage of the short line to leave a silence. He slowly turned to Ariel and said, “And mine shall.”

In that gap between their lines, the entire universe shifts. Prospero has finally been forced to make his decision about dealing with the traitors. This, of course, leads to one of the most famous lines in the canon: “The rarer action is / In virtue than in vengeance.” Chris showed us that this moment was the emotional center of The Tempest. He was not just an ingeniously gifted performer, he was a virtuosic storyteller.

It’s poignant that Chris’s last role onstage was in his own play, A Word or Two, and while that piece was autobiographical, he always placed the spotlight on the literature. All eyes in the theatre were often on him; he had boundless charm, the common touch. But he always knew exactly where the focus should be so that the play would absolutely land.

The loss of Christopher Plummer to the international theatre is gargantuan. Anyone who was lucky enough to be his friend is currently embracing the darkest shade of blue. Someone said to me after his final, elegant exit, “Ah, but he was 91.” My answer to that is, “No, he wasn’t. He was 67 and 22; he was 49, with the curiosity of a 6-year-old and the wisdom of Methuselah.” Like all truly great artists, Christopher contained multitudes. He wasn’t just 91. He was timeless. We are not likely to encounter a talent like his any time soon.

Des McAnuff is a Tony-winning director and former artistic director of the Stratford Festival and of La Jolla Playhouse.