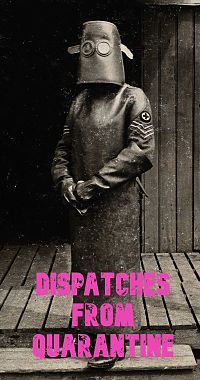

With COVID-19 throwing us all indoors and in quarantine last spring, the theatre faculty at Tennessee State University decided the best, most forward-thinking practice would be to produce an online theatrical season for the fall 2020 academic year.

With COVID-19 throwing us all indoors and in quarantine last spring, the theatre faculty at Tennessee State University decided the best, most forward-thinking practice would be to produce an online theatrical season for the fall 2020 academic year.

It would truly be a test of our united skills as faculty and students to pull off a full-length licensed play on the Zoom platform. We knew it would be historic, as by our October show dates, we would be among the first university theatre programs—either at predominantly white institution or a historically black college or university, as TSU is—in the United States to do so.

I decided we should highlight the voices of Black women, especially after the murder of Breonna Taylor. Being Black and from Louisville myself, it is an internal moral mandate for me to use my cisgender male privilege to recognize and uplift the voice of Black women playwrights where I can, when I can. As the published and licensed Western theatrical canon is overwhelmingly white and male, I wanted to use our budgeted funds to financially support a Black woman. If Black life matters, so must Black woman thought.

After reading several scripts I landed on Jump by Charly Evon Simpson, a newer work and a piece that is right on time. In it, Simpson uses magical realism to investigate Black mothers and daughters, sisters, and fathers while deftly handling mental health issues and intimate partner violence while also making us laugh and experience joy. We see the love among all of these relationships, which she makes leap off the page with such dynamism.

The play having been chosen and licensing paid for, the next step was auditioning and casting the piece, which started the process—first for me, later for my production team—of learning as we go. This was theory and practice happening simultaneously, as what I would theorize would either work in real time or fail in real time; immediate pivoting became a vital skill. This is where Blackness came in as a huge advantage, as no one can adapt like we can—we have been doing it since 1619 and have managed to thrive in spite of enslavement, pandemic, or state-sanctioned murder. Necessity is the mother of invention, and that mother is Black.

When students were slow to RSVP to Zoom invites for auditions that were sent out via email blast to the university, I made the first pandemic pivot: I posted on Facebook about them. The social media post garnered us an incredible community actor, Cris Eli Blak, the only non-TSU student in the show. I cannot imagine the show now without Blak, who asked to audition because he was excited at the possibility of doing a new work by a Black woman. His commitment to our community and culture was a recurring theme among the students and team during the process. Our students suffered greatly during this pandemic, and their dedication to telling this story for the world showed up in multiple ways, from a student spending much-needed money on a prop that was vital to the show (that I later reimbursed them for) to a student actually attending rehearsal from the very house in which a funeral repast was taking place after a death in the family.

Costume design by Prof. Eric Franzen expressed the culture, as a Black Lives Matter shirt appeared in his design sketches to me. For our Zoom background, scenic artist David Brandon used a color scheme that not only told the story well, artfully serving the scenes, but complemented the skin tones of our actors. Hundreds of images were drafted and edited, and we pored over each one as we normally would in production meetings, except that instead of dealing with how these may read on a stage, we needed to factor in how the colors would be best optimized for a phone screen. In practice this called for hours of plopping the actors in front of multiple backgrounds and having them play the scene; only then could the designer and I tell if the colors read as too loud or too soft. Some might have worked onstage, but in the small space of the Zoom ratio were just too much.

We were able to source inexpensive green fabric and mail it out to the performers, and webhad a Zoom session on how to mount their “green screen” on multiple surfaces, from dorm room walls to finished living rooms in multiple states of residence. Considering color schemes and matching them to the skin tone of your actors is something you must do onstage in traditional in-person theatre if you are being culturally conscious (as an Equity actor, I can assure you this is not always done in professional theatre). In Zoom theatre, both costuming and backgrounds present new challenges, as you cannot control the various light sources as easily as you can in-person theatre. Indeed, with Zoom theatre, we found that all of our actors were individually standing in different “theatres”: basements, hallways, kitchens, what have you, with different lighting and space capabilities. This was quite the challenge to overcome.

We could not simply change out a blouse or skirt, dye something a different color, or change a light gel. In Zoom theatre you must work with what the student has, and that may be fluorescent lighting or an old desk lamp. Some costume pieces were mailed out, but the innovation and pandemic pivot here was that the individual costumes that our designer drafted with my directorial input were then co-curated with students. We had to “shop” in their closets to come as close as possible to realize our design. Figuring that out in concert with the students was a painstaking process that took days of trial and error in rehearsal.

Best blocking practices in this medium also took some time to work out. As this was neither film nor television, and would conceivably be viewed on all sorts of devices, from a phone screen to a laptop to a large smart TV, I had to keep different screen ratios in mind. That meant I needed to think differently in terms of blocking and staging scenes for this live digital production.

Again, Blackness is suited for these pandemic pivot opportunities: Approximately 100 hours of Zoom time, between production meetings and rehearsal, made this show happen. Something beautiful about the production team, which was not lost on me—especially in these past few weeks, as our country descended into madness and white supremacy literally attacked the Capitol—was our diversity. Gay and hetero, Black and white artists, came together to support Black students in bringing the words of a Black woman to life for the world to see.

Creating digital space for audience feedback was important to me as well. As we were not in a shared tactile space, I wanted to make sure to create a safe space for all to process the show, as its themes of suicidal ideation and intimate partner violence could obviously be triggering. I started the hastag #howareyoujudy, named for one of the play’s characters, on Facebook, which went along with a Zoom talkback with licensed mental health counselor Brittany A. Johnson. I thought it was essential to have a Black woman health practitioner lead the conversation. She of course was supplied the text of the play, and watched the show. We had a debriefing session before we had the talkback to go over a rough roadmap of topics of conversation, but no questions were supplied to her in advance, as I wanted the conversation to flow freely and organically. We let the audience guide the conversation for the most part.

Johnson brought up the CDC report that pointed out COVID-19 was doing immense mental health damage to us all. This correlated to the audience response; one student actor mentioned that her friends noticed the romantic connection she has with another character in the play, but not the mental health issues. Johnson noted that “as Black people we tend to brush off mental health as a ‘white people problem’ and just push on through.” This is so dangerous to Black life as a collective. And that’s why this conversation—with cast, production team, and audience talking on camera about race, mental health, suicide, joy, what they loved and what they did not understand in the show—was the real point of all of this.

A community of diverse bodies coming together to encounter a Black narrative, experience it fully, and come away changed—this, in my estimation is one of the highest aims of the theatre. When Equity theatre was dark in Nashville and theatres around the country, our students and faculty came together to make a beautiful thing.

William Flood (he/him) is an assistant professor of theatre in the department of communications at Tennessee State University. A proud member of Actors Equity who goes by the stage name Billy Flood, he has over 20 years of experience in showbiz and has toured the country in musicals.