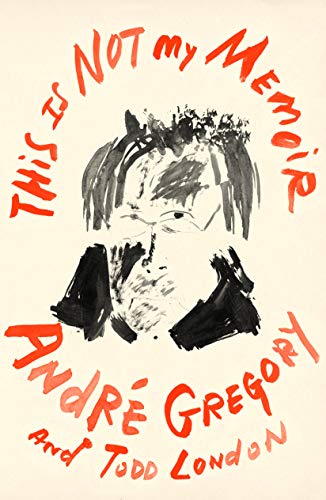

André Gregory’s This Is Not My Memoir, written with Todd London and from which the following excerpt is reprinted, can be purchased here.

Erland Josephson, the great Swedish actor, once said to me: “I went to great teachers to learn about the voice. I went to great teachers to learn about the emotions. I went to great teachers to learn about expressing oneself physically. What I would now like to do is find a teacher who could show me how to walk down to the footlights and—by just standing there, by doing nothing—be like a lighthouse illuminating and giving hope to the audience.” Might this be part of the task of being human: to keep working on oneself, to go higher on the ladder so your life can be more like a work of art itself?

❦

I was always looking for a teacher. I was always looking for a father.

Gordon Craig was my first great inspiration, and he was long dead. The illegitimate son of Ellen Terry, a legendary English actress of the nineteenth century, Craig, a set designer and director, was a visionary who could not fulfill his visions. He could not make them concrete on the stage. He was one of those marvels of nature who inspired me when I was still a teenager. I couldn’t see his work, but I could read his books and through immersing myself in his drawings and designs, I could dream. I could dream about the possibilities of a theatre not rooted in soap opera naturalism. I could imagine a theatre that was extraordinary, a theatre of marvels.

I loved a story about Craig being invited by Stanislavski to direct Hamlet at the Moscow Art Theatre. Craig made the actors extend their arms, as if they were more than human—long, long extensions like figures in a Giacometti sculpture. They put out their arms as far as humans could, but he would run down the aisles, leap onto the stage, pull their arms—or try to—farther out of their shoulders. “Longer! Longer!” he cried, frustrated by the shortness of a human arm.

Many years ago I was on the little ferry going from the island of Lipari to Naples. On deck I began a conversation with a rather elderly, distinguished, well-dressed Italian gentleman. I was wearing a pea jacket, and early in the conversation he asked me where I got the jacket. “New York,” I answered. “Yes, but where in New York?” he asked. I told him I purchased it on Canal Street. “Where on Canal Street is the shop where you got your pea jacket?” he asked. “I have always wanted that kind of coat,” said the distinguished Italian gentleman.

We talked about other things, about Lipari, about Italy, and so an. But every once in a while he would return to the pea jacket. Finally, as we came into harbor he said, “May I ask you what kind of work you do?” “I’m a theatre director,” I replied. “Oh,” he said. “Perhaps you have heard of my great-great-uncle Gordon Craig?” I took off my jacket and put it on the man’s shoulders.

❦

Perhaps what we call a vocation—a calling—is something passed on from generation to generation. People reaching into the well of time. In the theatre this calling stretches back through Jerzy Grotowski to Yevgeny Vakhtangov to Vsevolod Meyerhold to Stanislavski and Eleanor Duse and Gordon Craig to Molière to Shakespeare to Sophocles. They call us. I don’t know how they do this, but perhaps they do. This is what my friend the psychologist James Hillman termed taking our place in the long line of our ancestors.

❦

Bertolt Brecht, the great German director and playwright, was my next inspiration, but he, too, had died before I could know him. A professor of mine at Harvard, Robert Chapman, found out that I was going to work at the Brussels Expo and told me, “You must visit the Brecht theatre.” And so I did. The World’s Fair in Brussels ended and, while Chiquita and I planned our wedding, I made my way to Berlin. I had no idea what “the Brecht theatre” was and no inkling that it would change my life. I went for a weekend and stayed nearly two months.

East Berlin under Soviet occupation was terrifying. With little electricity there were no streetlights. The only buildings that were lit at night were embassies, theatres, and the legendary Hotel Adlon. That was it. You could turn a corner and find yourself facing a Soviet tank. On certain holidays the East German army would march for hours, goose-stepping like Nazis. The place was incredibly poor. There was nothing in the stores. Nowhere to eat. Bookstores carried hardly anything but propaganda books and plays by Brecht. The city seemed shrouded, sad.

Taking the subway through Friedrichstrasse from West to East Berlin was a frightening way to reach a frightening city. I was headed to the famed Berliner Ensemble, considered the greatest theatre in Europe, but I was on my own. I have never liked being alone; alone feels lonely. This time it also felt strange and scary. I didn’t know what was waiting for me. I didn’t speak German. The border was swarming with toughs, cold-eyed secret police, recruited from the farthest east of East Germany, where they were unlikely to have friends or relatives in Berlin. They could be ruthlessly impersonal. I was carrying, for comfort, a book. A guard grabbed it and tore it to pieces. I have always loved the theatre and been willing to go anywhere to find it, to learn, to be inspired. But this journey through the postwar world, in my early twenties, terrified me.

And then I arrived at the Berliner Ensemble: Mecca.

Brecht and his wife, Helene Weigel, had founded the theatre in 1949, when he’d returned to Berlin from his wartime exile in the United States, from which he’d fled after being compelled to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He’d made the company a seminal, groundbreaking world theatre, largely through his new productions of his own previously staged plays, including Mother Courage and Her Children and The Caucasian Chalk Circle, as well as, later, premieres of unproduced plays he’d written during the war, directed by his team of associate directors. After all, they were a Marxist collective. The work was steeped in Marxism and, to some extent, Brecht’s own theatrical theories. Plays were rehearsed over long periods of time with extraordinary rigor and painstaking precision. Brecht had died in 1956, two years before I arrived on his doorstep.

The outside of the Ensemble’s building, Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, was still pockmarked with bullets from when the Soviets took over Berlin. Even the men’s rooms were riddled with bullet holes, a jarring contrast to a theatre so full of energy and light. The building’s interior was striking, unexpected. Brecht had borrowed or purchased golden baroque angels from all over the Soviet zone, and he’d covered the auditorium, like a wedding cake, with these cherubs and with red plush carpeting. The productions, on the other hand, were often sparse, minimal, and confrontational, contradicting the sumptuous surroundings. The set for Galileo was three huge walls and a ceiling of glowing, beaten burnt copper. Because everything was scarce, the East German parliament passed legislation “asking” citizens to loan the theatre their old copper pipes. These would be replaced with new copper—or so was the hope—at a later date. The past, with all its beauty and horror, literally surrounded the future; the old lived side by side with the new. Brecht always wanted you to think and think and think.

The contradictions were everywhere. In the audience Soviet Politburo big shots and their wives sat elbow to elbow with the Western intellectuals who poured in from around the world. The word was out. The Berliner Ensemble had become known as the finest, most innovative company since the great Russian theatres of the ’20s, the pride of the state. In New York in the 1940s Brecht had noticed that the walls surrounding construction sites had old doors in them, with peepholes so passersby could watch the building going up. Why shouldn’t people be able to watch a production going up? And so, each day, about 200 of us watched rehearsal. Among these eager spectators, at that same time, was a young Polish director named Jerzy Grotowski. We never met.

The marquee poster for the night I arrived read: Das Leben von Galilei. I didn’t speak a word of German, and I knew only one Brecht play, The Threepenny Opera, so I thought I was about to see something called The Good Fisherman of Galilee. The Life of Galileo (the actual title) lasted over four hours. I couldn’t make out a word, and yet I understood almost everything. “How is that possible?” you might ask. Here’s how: Every moment onstage was fully explored; every gesture told not one story but everything important about that story: where the characters came from, what their economic circumstances were, what the dynamics between them signified. They had rehearsed over a long period of time, so that each event (a word I’ll talk more about later), every piece of the story rang dear and, somehow, became universal.

Brecht’s widow, Helene Weigel, was unbelievably hospitable to me. She found me a small apartment, introduced me to a few of the actors, had me over for tea. I even imagined—or did I actually see it?—that she winked at me and threw her skirt up during a musical revue.

Years later I realized, to my enormous regret, that Weigel might have wanted to have an affair with me. But I was only 24 and didn’t realize that women in their fifties had sex. What an adventure that would’ve been! What a roller coaster!

❦

My ideal theatre would be a theatre of miracles, and Brecht knew how to make miracles happen. Back in East Berlin someone told him about a marvelous singer performing in the subway, which was still in ruins from being flooded by the Soviet army. Brecht went to hear this young subway singer and, after the performance, told him that he had a beautiful voice. Brecht told the singer about the theatre he hoped to create one day and asked if he, Ekkehard Schall, would like to be part of the company. “Before we start work, though, you must develop your body to supplement your voice.” Based on this iffy offer, Schall trained to become a high-wire aerialist in Germany, a commitment that went way beyond mere training. It came from the belief that great performance requires great devotion.

Schall played the title role in Brecht’s Arturo Ui. Ui is a terrifying cartoon version of Hitler crossed with Richard III and Charlie Chaplin. The play takes place in Al Capone’s Chicago. At one moment in the play four or five gangsters approach Ui/Hitler to assassinate him. Terrified, Schall/Ui began to froth at the mouth, some kind of black bile. I kid you not. I saw this performance many, many times. It wasn’t a trick. The actor then did a triple backward somersault from a standing position, landed on the back of the couch, standing, with two drawn revolvers, and shot his would-be assassins. Now, that is miraculous.

And then there is the miracle of dedication. Schall prepared by watching hours of documentaries on Hitler for two years. He didn’t play at Hitler; he was Hitler. At the end of the play he walked toward the audience from upstage, screaming about conquering America and France. The audience literally recoiled in horror. The ruins of the Reichstag were only blocks away.

❦

As I was at the beginning of my education as a young director, as well as a nervous, nerdy intellectual, I asked Helene Weigel about the Verfremdungseffekt, Brecht’s famous “alienation effect” theory. The “V-effekt” proposes distancing the audience from emotionally identifying with the characters in order to elicit a conscious, intelligent response to dramatic material. This thinking response—as opposed to the usual feeling one—actively engages the audience, thus inspiring action. By provoking thought and action, Brecht meant to overthrow the passive emotionalism of theatre that aims for what Aristotle called catharsis. Weigel laughed and said something like, “Don’t pay any attention to Bert’s bullshit and theoretical nonsense. Just look at the work. Look at the work, and see what you see.”

When you looked at Helene Weigel you could see in her face the lines of great experience. This was a fierce woman who, with Brecht, trekked across the Soviet Union to China, through China, traveling on to Los Angeles, in order to escape the Nazis. This was the woman for whom Brecht had written the role of Mother Courage.

“Look at the work,” she ordered. And I did. Mostly I watched them rehearse Arturo Ui, but the first rehearsals I attended were for a one-act play, The Jewish Wife, that Brecht had written for Weigel in the mid-’30s. I believe they were readying it to reenter the repertory. Brecht had originally directed the play, and Weigel told a story about their work on it that I’ve never forgotten. In this brief series of three monologues, a Jewish woman married to a successful Aryan doctor prepares to leave Germany and, implicitly, her husband. She calls three close friends to tell them of her plans to emigrate. Each section begins with the line, “I’m leaving.”

Each time Weigel said the line, she would begin to weep. “No, no,” Brecht barked. “Sentimental! Its sentimental.” (This was a dirty word at the Ensemble.) “You only say that because you are a man and don’t understand women,” Weigel barked back. “I wrote it, damn it, and I know what I wrote,” the playwright yelled.

“Well, I have to act it!” replied the actress. They quarreled in front of a large invited audience. “Well, do it again,” he commanded.

And she did. More tears. “It’s awful. Sentimental.” Frustrated, Brecht suggested they rehearse the next day without him. (Rehearsing without the director, in a Marxist collective, meant working with his team of eight associate directors.) The next day, in character, Weigel picked up the phone to call her friends. Brecht was on the other end of the line, having somehow had his phone connected to the one onstage. He started telling her personal stories, jokes about their sex life. This time, when she repeated, “I’m leaving,” instead of tears came a chilling laugh. Weigel finished the story by walking to the lip of the stage, and speaking directly to the two hundred observers: “What Bert wanted to teach us is that a woman with the courage to leave everything doesn’t cry. She laughs!” Learn, learn, always learning.

❦

I learned most of what I know about directing at the Ensemble: about clarity, about taking the time you need to perfect a work. Theatre, I learned from Brecht after his death, is not a casual endeavor. It is Art, no different than painting, musical composition, or novel writing. It is Art and, as such, it deserves the money it needs and the time it needs. And it’s worth whatever it takes.

One other thing I learned from my German artistic daddy: Over his desk at the Berliner Ensemble hung a large banner, “SIMPLER AND WITH MORE LAUGHTER.”

Excerpted from This Is Not by Memoir by André Gregory and Todd London. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, November 2020. Copyright © 2020 by André Gregory and Todd London. All rights reserved.