Path-breaking director and Mabou Mines co-founder Lee Breuer died on Jan. 3. He was 83. Another memorial tribute to Breuer can be read here.

With Lee Breuer’s death on Jan. 3 at age 83, the theatre lost a beacon of creativity and spunk. Lee had been staging complex, layered works in New York and around the world for more than half a century. Typically writing or adapting texts himself, he often collaborated with puppeteers and musicians. The epic series of “animations” he developed over 35 years—his magnum opus, in a sense—combined polyphonic, semi-fractured narratives and images to render surreal mind-worlds visible and tangible. He also staged radically reconceived classics from Sophocles to Beckett, and other original plays, including, with a wink at the Italian Futurists, one that featured a forklift ballet.

A few of Lee’s productions reached the mainstream—the most famous being The Gospel at Colonus, in which he transposed Sophocles’ tragedy into an evangelical celebration. In his version, the Institutional Radio Choir of Brooklyn sang the role of the Greek chorus (using Lee’s lyrics and music by Bob Telson), and Sophocles’ “messenger” became a preacher (originally played by Morgan Freeman). Blind Oedipus was played simultaneously by all five of the a cappella Five Blind Boys of Alabama. Gospel at Colonus opened in 1983 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, toured internationally, moved to Broadway, was telecast on PBS’s Great Performances, and has been revived periodically, most recently two years ago at the Delacorte Theatre in Central Park.

Another popular show was Mabou Mines DollHouse, adapted from Ibsen by Lee and his partner in life and work, Maude Mitchell. In this production average-sized women playing the female roles performed alongside little people cast as the men. The miniaturized set was scaled to fit the men, underscoring how the world in Ibsen’s play is designed for men. After its 1983 opening at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn, Mabou Mines DollHouse toured nationally as well as in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

In 2011, Lee directed Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire at the Comédie-Française, making him the first non-European to direct in the Comédie’s main Salle Richelieu. His production, designed by Basil Twist, was also the first non-European play staged in the Salle Richelieu. Capping the honor, on opening night the French Minister of Culture presented Lee with the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, which had been bestowed six years earlier but Lee hadn’t yet collected.

Notwithstanding such occasional forays into A-list venues, Lee planted himself mainly in the noncommercial world of off-off-Broadway, which is where I first saw his work in the early 1970s. In off-off theatres such as La MaMa and, later, PS122, he could experiment with kinds of staging he had never seen and with content that could be more cubist (his word) than linear. Lee thrived there, continually developing new work. His directing and the actors he directed garnered 20 Obie awards. He refused his Tony nomination for Gospel. He was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 1985. He received a MacArthur “genius” award in 1997.

Esser Leopold Breuer was born on Feb. 6, 1937 in a middle-class Philadelphia family. He entered UCLA at in 1953, at age 16, majored in English, and began to write plays. At UCLA, he also met his long-term personal and artistic partner, Ruth Maleczech, and they had two children (whom Lee often cast in shows). Ruth and Lee eventually married in 1978 and remained married until she died in 2013, though they had long since separated and he had had three more children with three other women. Lee met Maude Mitchell in 1999. They soon began to work and live together, marrying in 2015. Maude and Lee were together until his death last week.

Lee’s artistic journey after college took him to San Francisco, where he directed at several area theatres, including at the famous San Francisco Actors Workshop from 1963-1965. When the workshop’s leaders moved on to found the Vivian Beaumont Theater at the brand new Lincoln Center in New York City, Lee and Ruth headed to Paris, where they at first stayed with their friends Philip Glass and JoAnne Akalaitis, sleeping on the floor. Lee and Ruth ended up living in Paris for five years, visiting bastions of European experimental theatre, including Grotowski’s little company in Poland and Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble. They began staging small-scale shows, including a group of Beckett plays, in Paris.

In 1970, the couple returned to America, and Mabou Mines Theater came into being. Named for the small Nova Scotia mining town where they had held an initial workshop, the company consisted of: Lee Breuer, Ruth Malaczech, JoAnne Akalaitis, Philip Glass, and David Warrilow. They figured, Lee said, if Grotowski’s “little group of artists in a basement in a nothing town in Poland” could have such a major impact, a little group like theirs, with work that was “distinctive enough that you really have something to say,” could “make a dent.”

They were keen to make all of their work collaborative, partly inspired by the Berliner Ensemble, where they had seen that everyone gave feedback as shows developed. In first few years, new actors, including Fred Neumann and Bill Raymond, joined the company. Several members directed their own shows.

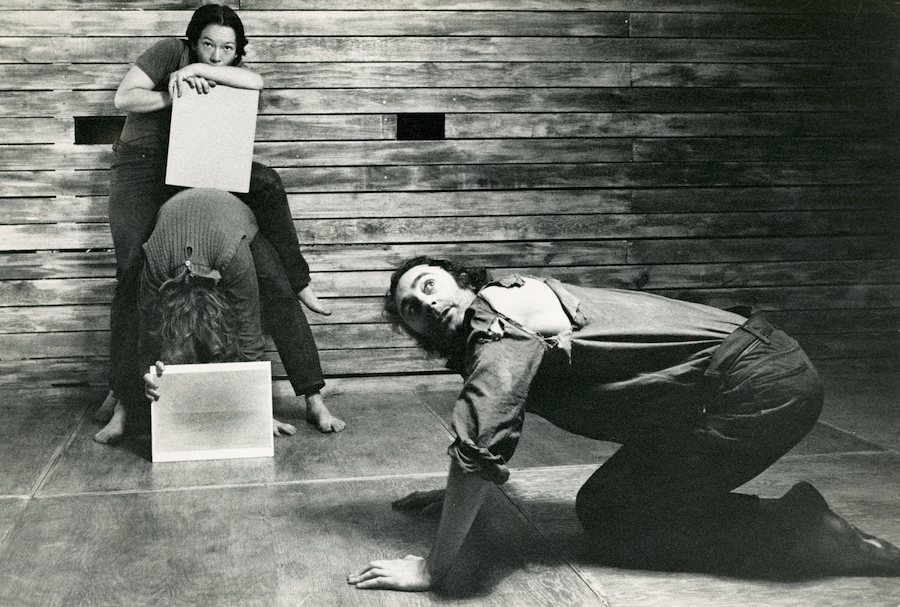

But the dominant force in Mabou Mines was Lee. During its initial season, the company staged the first of his many “animations,” The Red Horse Animation (1970), about the creative process of bringing a vision to life. The show played first at the Guggenheim Museum, then at La MaMa, then in venues around the country.

It was in these early years that Lee also directed several innovative productions of Beckett. In Come and Go (1972), audiences could see only the mirrored reflections of the performers, not the actual actors. In The Lost Ones (1975), David Warrilow narrated and manipulated inch-high inhabitants in a hopeless, confined world. But he slid the scale and the focus between the tiny people and himself as he also became an “inhabitant.” Those Beckett productions remain legendary in the experimental theatre world—each in its own way heart-stopping. Warrilow’s performance garnered the troupe’s first Obie. By then, the company had shown that it “was distinctive enough,” and “had something to say.”

Lee could elicit remarkable performances, Maude has told me, because of his belief that the director truly collaborates with the actor. Rather than trying to elicit a particular interpretation, Lee selected from and tried to expand what the actor brought. Lee “built a diving platform for the actor,” she said. Encouraged and supported, the actors sometimes discovered that they could dare to fly.

I attended Lee’s rehearsals from time to time over several decades, and I saw again and again that a part of his genius was that the man was an idea faucet. His ideas—for staging, language, everything—just kept coming nonstop. There were inspired ideas. Off-the-wall ideas. Blind-alley ideas. Inspired, off-the-wall, blind-alley ideas. And, of course, ideas for fun, cheap effects and puns. It didn’t much matter if a show was about to open. The ideas kept spilling out. Days before the opening of Streetcar in Paris, Basil told me he didn’t dare leave the theatre for half an hour. “I’d come back and it’s like, ‘What just happened here?’”

To me, Lee’s most interesting ideas were ones that started as one thing and later metamorphosed into something quite different. He might never have reached the final idea without the false start. For example, in his first iteration of Oedipus at Colonus, Lee worked with the doo-wop group 14 Karat Soul. Sophocles’s play got a contemporary musical realization, as Lee wanted, but the spirit was clearly wrong. That 14 Carat Soul collaboration, though, led to Sister Suzie Cinema (1980). And, most importantly, Lee’s Oedipus at Colonus project later moved from doo-wop to gospel and became the stuff of theatrical history.

Lee’s Paris production of A Streetcar Named Desire (Un Tramway nommé désir) was a gem of iffy ideas that worked—though mostly not as originally conceived. Lee wanted to pay homage to Elia Kazan’s iconic film of Streetcar, so he chose to have a set made of screens. He also wanted the audience’s viewing angle on various rooms to change, to replicate the effect of different camera angles. In the end, Basil’s exquisite panels in no way suggested movie screens, but the images they showed carried subtext: a Jack Daniels bottle when Blanche needed a drink, a tiger when the women talked about Stanley. And like old-fashioned stage wings, they funneled the audience’s attention to the action. Meanwhile, the changing “camera” perspectives did not suggest a movie, but they did help to pull the audience’s focus inside the rooms.

Lee and Basil’s decades-long collaboration nourished both of them enormously. They worked together on half a dozen shows, and Basil describes Lee as his “hero.” Two major collaborations were Peter and Wendy (1996) and Red Beads (2005), both shows on or well over the edge of traditional puppetry. In Peter and Wendy, written by Liza Lorwin (mother of one of Lee’s sons), Peter and Captain Hook were bunraku puppets, with their three handlers apiece veiled under white hats to look Victorian. (Lee’s son Lute was lead puppeteer for Hook.) Karen Kandel, sans puppet, played Wendy and spoke everyone’s lines, sometimes in rapid repartee with herself. And in a lovely coup de théâtre, the family dog donned a flimsy crocodile disguise in order to watch over his young charges in Neverland.

Red Beads (2005), another Lee/Basil collaboration, is a disturbing play about adolescent sexuality, based on a story by Polina Klimovitskaya (mother of another of Lee’s sons). It featured Clove Galilee (Ruth and Lee’s daughter) along with her mother. Clove wanted to explore aerial dancing, suspended by a cable, and Basil had long wanted to try out wind puppetry—puppets manipulated by fans. In the final staging, actors flew and danced with diaphanous costumes wafting in choreographed currents of air. Lee and Basil revived the technique years later for one scene of Streetcar.

Lee collaborated with other artists as well, both in and outside Mabou Mines. After working together on Gospel at Colonus, he and composer Bob Telson joined forces again for The Warrior Ant (1986). A remarkable presence in that show was bunraku master Yoshida Tamamatsu. Never before had a certified bunraku artist taken his art totally outside its established tradition. Tamamatsu, for example, manipulated his puppet to dance a sexy tango. In Lee’s next iteration of the insect epic, The MahabharANTa (1992), he paired with I Wayan Wija, one of Bali’s top shadow puppeteers, who, in Bali as well as abroad, continually explores new possibilities for the shadows.

In La Divina Caricatura (2013), the last animation Lee got to mount, he worked with composer Lincoln Schleifer and eight singers, using styles from 1950s pop to rap to Gregorian chant. Fifteen puppeteers manipulated traditional-type bunraku puppets. The show featured Rose the dog, a frequent star of Lee’s animations, and her beloved human, the dope-addicted John. Rose embarked on a Dantean journey, which was also a treatment program for “love addiction,” launching the proceedings into a blithely illogical, pop-surreal extravaganza. Like all his animations, Lee said, La Divina Caricatura was autobiographical: “This is a metaphor for the artistic life, a pilgrimage to—God-knows-what.” The epic quest, he said, was in pursuit of ideal art. Or ideal love. Or maybe they were the same thing.

Anyone who knew Lee knew he relished the role of enfant terrible. He loved being outrageous, whether presenting a dog puppet having phone sex with his master (in an early version of La Divina Caricatura), choreographing a ballet for forklifts (in 1973’s The Saint and the Football Player), or wearing plastic bags for socks.

Although Lee could come across as a huckster dealmaker, he devoted all his resources—physical, emotional, and financial—to his art. Despite being one of the most important theatre artists in America, he always lived on the edge of poverty. Lee and Maude stayed rent-free for the past 20 years in a studio apartment provided by a friend. Without that boon, she recently told me, they could not have managed to do the work they did.

Lee had been sick on and off for nearly 17 years, with kidney disease, lung cancer, and a host of other ailments. He slowed down only as much as absolutely necessary to stay alive. Until two weeks before his death, he was working on a new text about Gulliver, to maybe become an animation. What mattered to Lee always were work and family. In his last weeks, Lee was surrounded by his children and his wife. Maude told me a few days ago, “He had a good death.”

Eileen Blumenthal (she/her) is a critic and scholar based in New York City.