About a third of the way through their final presentation, the students in New York Theatre Workshop’s inaugural Youth Artistic Instigator program delivered a message. The audience for this message wasn’t necessarily the group of people watching this Zoom production, an audience comprising families, friends, and guests, though its sentiment likely rang true for many listening. Rather, in the aptly titled Dear Teenagers, these 25 students from around the country, siloed due to an ongoing pandemic, delivered a letter of support to their community. “I am proud of you,” one line read, with another encouraging, “Be who you want to be.” But perhaps the most pointed line from the piece managed to be similarly encouraging, while also encapsulating the message of NYTW’s program overall: “The voice of a teenager is one to be reckoned with.”

“As a young adult, we are often silenced by nothing other than our age,” said Shareef Kinslow (he/him), 17, after one of the workshop sessions. “They say they’re listening, but it goes in one ear and out the other. This really created a space where our opinions mattered.”

The NYTW program, Kinslow explained, provided a rare opportunity. What the Off-Broadway company offered through its 10-week devising workshop was the chance for high school students across the country to gather as like-minded, passionate creatives, something that isn’t always the case at many schools, where the level of dedication to stage craft beyond the expectation of an easy positive final grade can vary significantly. More than that, though, this space opened the door for these students to grow artistically in a way that multiple students said that their classes rarely did.

“It’s so needed in so many ways, with how disruptive this time has been for high school students,” said teaching artist Nana Dakin (she/her), who led the 10-week program. “Theatre is the first place that I found my own sense of wholeness and agency as somebody the same age as these students. Devising in particular for me was the first way in which I learned how to tap into my own sense of agency as a person who can tell stories, and as a person whose ideas and points of view were interesting.”

NYTW’s youth artistic instigator program emerged from a question about how, in the midst of a pandemic, NYTW could continue to engage and program for young people. Typically, that engagement might look like artistic residencies in schools or partnerships with drama teachers to enhance the curriculum. But this semester, explained NYTW’s director of education, Alexander Santiago-Jirau (he/him), they weren’t sure what they were going to be able to provide. So they began to explore what could be done outside of the classroom.

The decision was made to create a sort of ensemble, inspired by NYTW’s decision over the summer to dedicate programming to a group of artists from the community, said Santiago-Jirau. Those artistic instigators were given grants and a prompt to create work that speaks to the current moment, using the tools at their disposal to go out, dream, and bring their ideas back for NYTW to produce. Similarly, the youth artistic instigator program brought in a group of students to devise new pieces of work responding to current events that the students felt passionate about.

The goal, Dakin said, was to create a program that allowed these young artists the opportunity to gather, feel empowered about their voices and perspectives, and learn how to use theatre as a transformative tool. Students from New York, Illinois, Maryland, Mississippi, Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey, with passions spanning theatre, social justice, political activism, and civil engagement, were chosen for the first cohort.

“We all have something that we want to change, and we don’t know really how to do it,” said Sri Nath Kurup (he/him), 15. “This gave us an opportunity.”

Over the weekly Tuesday afternoon sessions, students learned the fundamentals of devising from director and deviser Dakin, drawing on everything from personal experiences to news stories to create monologues and scenes. To be clear, Dakin’s role—and the roles of support staff Santiago-Jirau, Adam Odesess-Rubin, and Gaven Trinidad—was primarily to guide students throughout the workshops, prioritizing growth and experimentation through collaboration. Throughout the multiple sessions I watched, there was never a sense of work being evaluated or judged. Rather, the “adults” in the Zoom room illuminated prompts, proposed the kind of work that could be made (a monologue, a scene between a person and their ancestor), then stepped back, allowing the students to determine the topics they’d like to create around and letting them be the driving force behind the feedback process.

“It was me in this piece. Even though it could be a made-up story, my heart is in it, and it feels so good to let that out and let other people know what you’re feeling.”

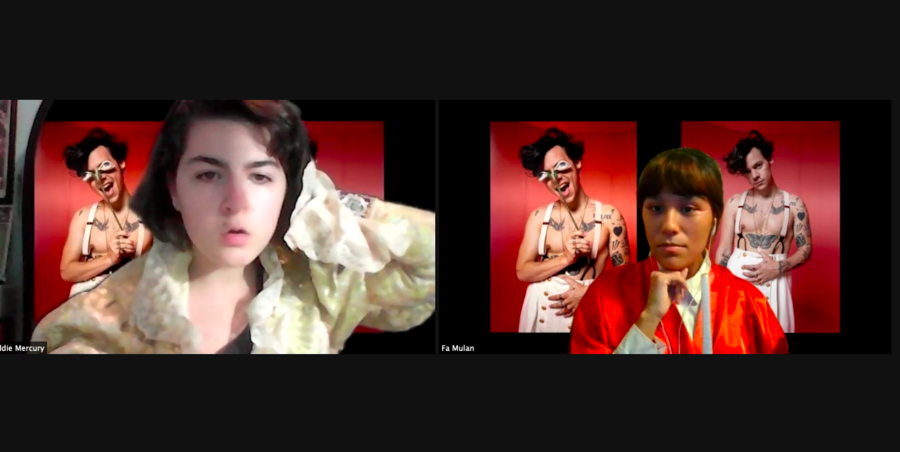

From there, the students shied away from nothing, diving into politics, the deaths of Emmett Till and George Floyd, racism, sexual assault, pollution, and even the discourse around Harry Styles’s choice of clothing—all topics that Dakin noted are experienced and interpreted remarkably differently by the mouths and minds of high schoolers. Through small groups in Zoom breakout rooms, students like Kinslow, who had previously seen writing as something isolating, found an opportunity to collaborate and learn how enjoyable it can be to bounce ideas off of peers without fear of criticism. With a time limit demanding new work be presented to their cohort, Kinslow said there was something fun about being in a pressured situation with others who came into it just as lost as he was.

“That’s an amazing thing,” Kinslow said, “when you can go from nothing to something. It’s a little bit of you, a little of that person, a little of the other person in the group. You all have this sense of ownership and pride about it.”

That ownership can move to a personal level for some. In one workshop exercise, Kurup took the opportunity to wrestle with his complicated relationship with his grandmother. The scene he created, which was one of the eight short pieces that made their way into the final presentation, was a fictional conversation between him and his grandmother. Through his dialogue, Kurup tried to figure out how he could make amends with her, as he felt he hadn’t treated her well when he was younger, and now she isn’t able to remember who he is. Like many playwrights, Kurup found himself grappling onstage with a real-life situation that didn’t have a real-life resolution.

“The solution was to just pick up the phone and call my grandmother,” Kurup said he realized during the program, leading to an ending of the piece, titled Out of Reach. “Even if it doesn’t change anything, I have to keep trying to move forward. I’m glad that I could learn and understand the writing process for a lot of these playwrights and authors who, when they write, it’s not a character, it’s a part of themselves. It was me in this piece. Even though it could be a made-up story, my heart is in it and it feels so good to let that out and let other people know what you’re feeling.”

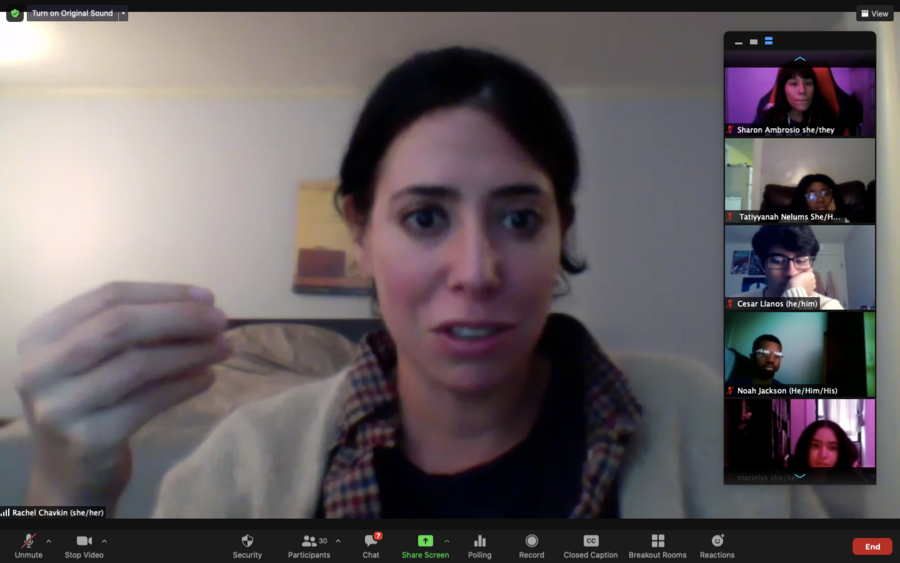

In addition to learning from Dakin, the students had the chance to pick the brains of award-winning artists like Martyna Majok and Rachel Chavkin. Again Dakin used interactions like these as a way to prioritize the artistic growth of these young instigators, stepping back and allowing the students to steer the conversations. In fact, Dakin tossed her session plan out the window when the conversation with Chavkin turned into a spirited two-hour, all-questions-on-the-table session with the Hadestown director.

Elizabeth Sumoza (she/her), 17, said she’s seen the advice Chavkin gave her, in addition to her overall experience with the program, already starting to affect school work. Previously, Sumoza found herself faced with writing prompts, stressed about finding the right place to start. The program and its deadlines have given Sumoza more confidence in writing under a time constraint. And Chavkin’s advice? Just start.

“It just seems like I don’t know what to do,” Sumoza said of facing that sort of writing block. “I have all these questions, ‘What if I did that?’ Sometimes you just need to start. This workshop was a good start for me, and now I’m ready to keep going.”

That’s the overall point here: to give these students something to take with them in the next steps of their artistic journeys. Even after the incredibly moving final performance the students delivered, multiple students were left feeling hungry for even more. Asked what feedback they’d give to NYTW on this program, Sumoza, Kurup, and Kinslow were in agreement: They simply wish there had been more time: more time to explore topics, more time to venture away from the prompts, and more time to create within this community that they’ve built.

Thankfully, this community and the skills these students have learned aren’t confined to official Zoom meetings. This is a community that has already spilled over from the two-hour weekly online sessions into middle-of-the-night group chats. It’s the people, after all, that were Kinslow’s favorite part of this experience, he said. Through Dakin’s leadership, and parallels to the overall theatre’s efforts to be more inclusive—including beginning each session with land acknowledgements and community guidelines—the students were able to find a respite from school as well as an artistic oasis.

Kurup said Dakin must have “some secret magic that she’s not telling us about,” because he would wind up feeling energetic and rejuvenated after these weeknight sessions, even though they followed full days of school meetings. Similarly, Sumoza valued the community’s ability to balance difficult, personal subjects with dance parties and general fun. Dakin recalled an early session when one of the students renamed themselves, changing the pronouns they were using with the cohort, because they felt comfortable enough to do so. “That actually meant a lot to me,” Dakin said, holding back tears. “I just felt like, ‘Thank God. That’s why we do this.'”

NYTW told me that the post-COVID dream for this program is that it become an in-person ensemble of young people in community with the theatre on a yearly basis, with the possibility of the virtual version also still sticking around. When asked before the program started what their benchmarks for success were, Dakin and Santiago-Jirau pointed to engagement and commitment to the work, in addition to making sure the students felt valued and empowered. These students, Dakin said, should be promised a functional world to step into, rather than the ceaseless uncertainty they’re facing.

“The baseline thing that I wish for is that the students do not feel alone,” Dakin said, “that they feel like they’re part of a group of people who share their passions, their energy, and their questions. If, on top of that, they can also feel like they have gained tools that have now empowered them to figure out how to creatively express their thoughts and ideas—that would make me very happy.”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor at American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org