In a previous lifetime, I was editor of the actor’s trade weekly Back Stage West, and the world of casting was one of my beats. By that I mean not only the dish about who got what role and the endless arguments about how they fared in it (Could anyone but Denzel have played Malcolm? Why were Brits taking all the American roles, but a couple of Americans landed two of the choicest hobbit roles? Who was the better Mama Rose, Bernadette or Patti?), but who helped put them there. I knew and collected the names of the casting directors—not casting agents, I was always quick to say—who were instrumental in the fine art of populating the worlds of the film, the TV show, the stage, the 30-second commercial. I was versed in the essential role that Ronnie Yeskel, for instance, played in Quentin Tarantino’s early films, or the way that John Levey filled out the ensemble of ER, or how the late Stanley Soble wrangled talent for the Mark Taper Forum stage. Stories like this were the subject of the only book I’ve written so far, How They Cast It, in which I told the stories of how everything from Friends to Real Women Have Curves, from The School of Rock to CSI to The Lord of the Rings found their casts (yes, Vin Diesel really did want to play Aragorn, and Leah Remini was, incredibly, the original favorite for Debra on Everybody Loves Raymond).

I also found, among all the industry folks I met and spoke to, a surprising personal affinity with casting directors. Yes, I loved talking to playwrights and directors and actors and designers. But with casting folks, as with fellow critics, I could nerd out about actors and directors and playwrights—they all seemed to know the same reference points I did, or turned me onto new faves. It didn’t hurt that many casting directors, even the ones who worked in TV and film, came from the theatre and accordingly populated the screens with stage actors I knew and loved. I found I was the kind of industry geek who particularly loved to watch the opening credits of a TV show to see the names of an episode’s guests, or who loved to look at my play program to see who was in what part. To this day I give a little cheer when I see a stage actor get their money (hello, Rebecca Naomi Jones for Nissan Rogue), and I now torment my kids by repeatedly telling them which Marvel or Harry Potter actors I’ve seen onstage.

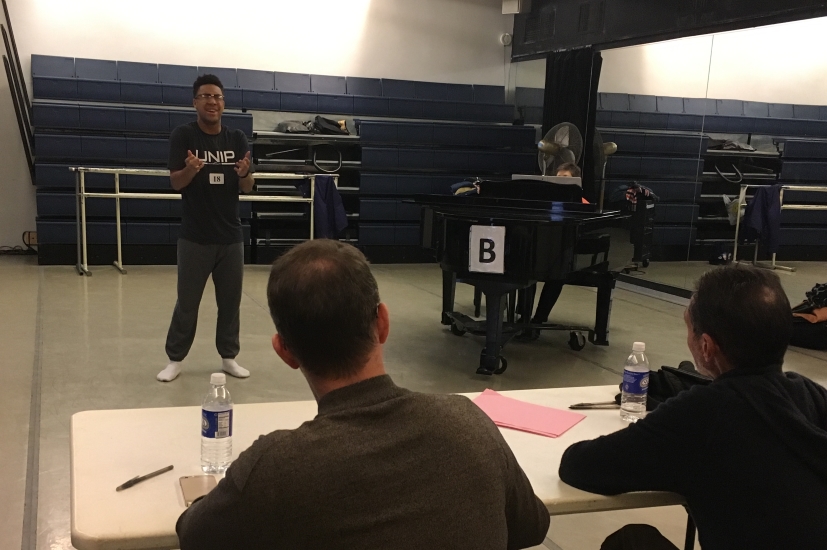

In an even more previous life I went to film school, thinking I wanted to direct, and there I heard the famous quote about the importance of casting—that it was 80 percent of directing. (Tracking down the original provenance of that quote is a bit of a rabbit hole, by the way: Often attributed to Elia Kazan, it has since been echoed by everyone from Robert Altman, who put the percentage number at 90, to John Frankenheimer, who scaled it down to a more conservative 65.) If that was true, I always wondered, why didn’t USC Film School teach it more proactively? When I went there, in the late ’80s, teaching us to direct actors was almost an afterthought, the subject of exactly one required class amid countless courses on how to shoot, light, cut, write, etc. Teaching us how to run an audition? Fuggedaboutit. I shudder at the awkward memory of the casting sessions I ran, especially for a film I made with no dialogue (and no pay).

What I’ve since learned is that whether or not you can fix a number to its importance, casting is about more than just the director’s vision—it’s about the world we see in the art and entertainment we consume. And for too long that world has been default white, cis, non-disabled, reflective not of the world we live in, let alone want to live in, but of the limited imaginations of creators and, yes, many of their their partners in casting. That is changing, slowly but surely, as actors and writers, not to mention audiences, demand art that speaks to their experience. But it’s a shift that we haven’t often seen covered from the casting angle.

Which is why I’m excited to share this special issue all about it. Jerald Raymond Pierce writes about efforts to diversify and train the field of casting professionals, and Allison Considine has a piece about how theatre training programs balance their students’ need for performance experience with the realities of casting, both in the school setting and in the professional world. Speaking of training programs, Yasmin Zacaria Mikhaiel hones in on a practice she’s seen too often taught, or at least not corrected or contextualized, in educational settings: whitewashed casting. Christopher Burris contributes a personal essay about how a mere change of headshot, and the racialized perceptions around them, led him on a different career path. There’s a roundup of casting folks and actors you should know about. And, of course, there’s our long “dream casting” survey, in which dozens of theatremakers and theatre observers told us who they’d like to see in what roles.

With this package of stories, I was able to recover some of my industry nerd delight. (At Back Stage West, we regularly wrote a feature nominating film casting directors’ work for an imaginary Casting Director Oscar, which I see the magazine is still advocating for.) And I also realized another reason this topic is so rich: It is the intersection of so many of the pleasure of narrative art (Faces! Voices! The way humans move!), and of many of its pains and challenges as well (brownface, stereotyping). So with this issue, I and my colleagues have had both the great joy of contemplating the extraordinary work of actors and the people who open doors for them, and the chance to dig into issues of representation, exclusion, and advocacy for change.

I’m not so naïve as to think that plays or films can by themselves help us imagine or entertain our way out of the towering problems we face in our world. But I do believe in the power of images and stories to expand our imagination, to make us think the unthought and see the unseen, and that’s a power we should neither take for granted nor treat lightly. Even—or especially—when we’re dream casting the next revival of Trouble in Mind.

Rob Weinert Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org