“There’s a bias at play,” said casting director Victor Vazquez (he/him). Vazquez was referring to what Actors’ Equity Association made clear in their second diversity report, which tracked the demographics of which union members were being hired. The report showed that there had only been minimal and inconsistent improvement for performers from marginalized communities. But it goes deeper and further than that, Vazquez pointed out: He sees evidence of the industry’s bias every time an actor who is Black, Indigenous, or a person of color (BIPOC) walks into an audition room and is surprised to see him in the chair across from them, or in the emails he receives from actors who say they’ve never auditioned for a non-white casting director before.

Indeed, Vazquez said, he only knows of a handful of BIPOC casting directors in New York City, out of the 100 or so Casting Society of America (CSA) members. That’s partly why he started his own company, X Casting. “To think that New York City, one of the most diverse cities in the world, a city so known for being a culture maker—that very few BIPOC folks sit at that seat was shocking to me,” Vazquez said. “It showed me in a big way that there was a problem.”

The casting director is a uniquely powerful shaper of the work we see in any medium, and the stage is no exception. It is in essence a curatorial and gatekeeping position, charged with surveying a city or region’s pool of actors and paring that down to the dozen, half dozen, or fewer who will be brought in to audition. The cohort who is brought in can depend heavily on the creativity and imagination—and yes, the background—-of the person in the casting director’s chair. Vazquez, who was born in Compton and grew up in Los Angeles, said that when he imagines the world of a play, his default is to picture a world that is almost 90 percent BIPOC people. That can be a strong corrective to the white-centric world views of so many other casting directors and creative people in the field.

“I often tell people that less than a thousand casting directors in the world are responsible for the curatorial engine that runs the way we interpret the world,” Vazquez said. “We’re casting TV, film, theatre, audio books, commercials, print ads, it’s everything.”

To be clear, casting directors don’t necessarily making the final decisions on who winds up in a production; that task usually falling to the director or producer on a project. But the value of a casting director’s position as an advocate with the power to affect who is considered in the first place cannot be undersold. For Vazquez, that meant rigorous discussions during his time leading Arena Stage’s casting efforts in Washington, D.C. Blocks away from the White House, with politicians, lawyers, and even Ruth Bader Ginsburg as regular attendees, he felt the importance and potential impact of these conversations about who is in the play and why that matters.

This idea of casting directors as advocates contrasts with some of the harsher perceptions of the position, in which casting directors wield immense power with an antagonistic edge. The uncomfortable yet somehow familiar story that Jason Robert Brown tells in “Climbing Uphill” in The Last Five Years springs to mind. As Cathy sings her audition song, she looks across the table and sees faces looking at anything—a crotch, her résumé, her shoes—other than her singing. Or there’s the stomach-churning trope of the actor hearing a curt “thank you” from the table early on in a monologue or song.

Though there are grains of truth in those popular images, what they miss is the art and empathy involved in casting, which extends far beyond the audition room. Casting, by necessity, has to be deeply rooted in a desire to understand other people—not only the performers but directors and writers as well. In order to perform their curatorial job, casting directors have to be able to understand the characters and motivations of the script, as well as the many actors who could bring those characters to life and create a vibrant world for the play.

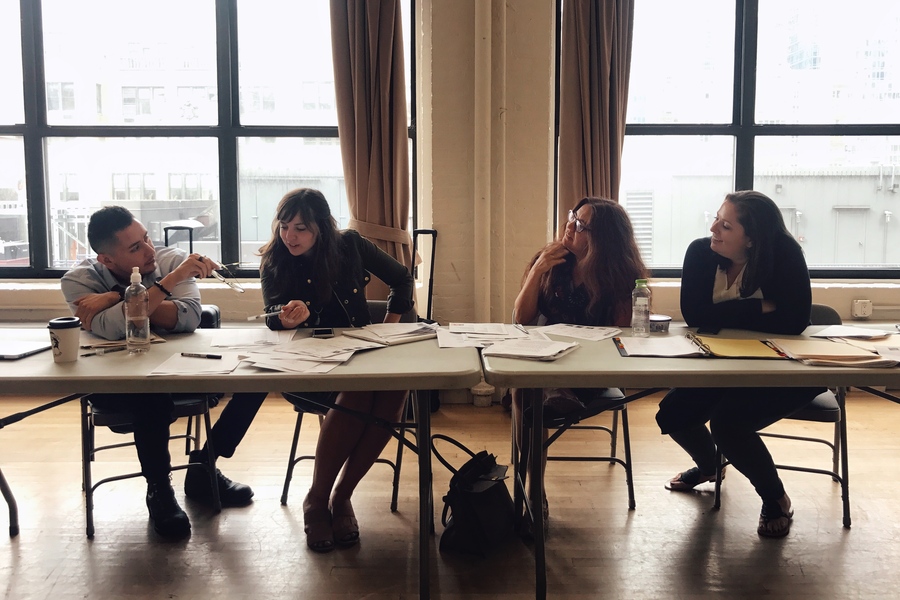

It’s here that casting directors have the chance to bring advocacy and activism into their work. For Playwrights Realm casting associate Ada Karamanyan (she/her), that means working through casting to change the idea that casting trans actors, or any underrepresented group, for that matter, is some “special skill” rather than something that is second nature for the creative team.

“There is an entire community of trans and gender nonconforming actors out there who have had virtually nobody going to bat for them behind the table,” Karamanyan said. “They’ve been doing it all themselves, pushing the movement forward, pushing themselves forward, pushing the acting community forward. It’s about time that they have somebody on the other side of the table.”

But, as in other areas of the field, there’s a pipeline issue. For years, the path to the casting director chair flowed through unpaid internships. As Vazquez put it, “It’s baffling that there is no way to study this—that the only way to get into this business is to be an apprentice to somebody else who can teach you and can hold the door open for you to come into this world. It’s no surprise that most people in the industry look like their predecessors.”

David Caparelliotis (he/him), whose company Caparelliotis Casting has a lengthy list of Broadway credits—including the Joe Mantello-directed production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and the Anna D. Shapiro-directed The Minutes, both closed in previews due to COVID-19—has recently started to reevaluate how he looks at internships. Before this year, Caparelliotis would have said that internships are the best way to break into casting, pointing out that it’s invaluable to have the likes of Tara Rubin or Bernard Telsey singing your praises when looking for a casting assistant position. But he also acknowledged that these unpaid internships have historically been a barrier to entering the field for any who can’t afford to work for free, which is especially problematic when looking at the demographics behind the casting table.

“Part of a casting director’s job is to be empathetic,” he continued, “to take the totality of a person in as you meet them. That said, I’m still a white guy of a certain age. So if I’m behind the table casting The Piano Lesson and actors of color are walking in and I’m the guy behind the table…” It’s not a deal breaker, he said, but that common disconnect “is not nothing.”

Caparelliotis himself took the traditional path to casting, interning at Manhattan Theatre Club’s casting office, eventually working as a casting associate there, then starting his own casting company with Melanie Nagler in 2007. Through that journey, Caparelliotis recalled, he was privileged enough to be able to work his full-time internship and fit in shifts as a waiter. Many people couldn’t and can’t afford to follow that path, which is certainly a major reason there’s a diversity problem at the top of the ladder. Regarding the industry’s inequality, Caparelliotis was blunt: “The basement’s been on fire for a long time and the fire has been rising higher.”

Caparelliotis noted that, until around a decade ago, many younger folks didn’t seem to see casting as a possible career choice. This might be because many, myself included, attend theatre programs that present a wide range of theatrical specialties to follow—degrees in design, playwriting, directing, stage management, company management, pedagogy, acting, dramaturgy, etc.—but a notable absence is casting. The result is that most, including many in Caparelliotis’s generation, who have been working for two or more decades, wind up in casting largely by chance.

Vazquez was an English major before studying directing and writing as an undergraduate. He was working in community partnerships and programming with companies like Center Theatre Group and Pasadena Playhouse, and casting was just one of his responsibilities. But then he joined Arena Stage and jumped into the deep end, overseeing Equity principal auditions for 10 shows just three days after his interview with the company.

Karamanyan was also a sort of jack-of-all-trades who aspired to be an actor, but who found her love of casting through conversations with Margaret Layne, casting director for Seattle’s A Contemporary Theatre. Another casting director, Caroline Liem (she/her), was the lone creative person from a medical family, starting out with her heart set on acting until she had a sort of epiphany in an audition: As she hit the high note in her audition song, she suddenly pictured herself on the other side of the table. She started casting two months later.

“People don’t know what casting directors do because it’s not in the course curriculum,” said Liem, who teaches at PACE School of the Arts and University of Texas at Austin. “What we’re finding is there are a lot of acting majors and performance majors who learn about casting and, much like myself, go, ‘Wait a minute, I can do that. I’ve cast plays myself. I’ve put on productions. I know what that looks like.’”

Many of those performers have skills that can translate to casting, even if they’ve never thought about it. Entry-level, foundational skills include organization, the ability to prioritize, the capacity to work with a variety of personalities, and the core practice of breaking down a script and understanding character. These abilities, which are already part of many theatrical fields, all translate easily to casting. Still, as Caparelliotis noted, there are always going to be specific nuances to those skills that will need to be learned in the world of casting, including understanding the various casting platforms and procedures.

Add to that the responsibility laid on the shoulders of casting directors to carry forward the vision of the producers, director, and playwright while also opening their minds to more possibilities for the production: Have they considered the character being played by a trans actor? How about an actor with a disability? These are critical questions to entrust to professionals with minimal area-specific training and a traditional path that asks many to start out working for free.

Even on CSA’s website, the prescribed path to casting director begins at casting assistant before moving up to casting associate, and eventually casting director. How might one gain the experience and knowledge to be hired as an assistant? The website’s explainer offers that you should have “a love of actors and acting, along with a voracious appetite for their work” before suggesting, “You might try working for a theatrical agent or manager, where you will learn how the business works, who the casting directors are, what areas they specialize in, and perhaps who is looking to add to their staff.” In other words: Could you simply get a job in the industry before getting a job in the industry?

Liem, who serves as CSA’s vice president of advocacy and a co-chair of CSA’s BIPOC alliance, noted that CSA is taking steps to bridge this gap between interested people and the field of casting. Casting Society Cares, a charitable division of Casting Society of America, has created a training and education program to provide opportunities for the next generation of casting professionals as well as to address the lack of equity within the specialty. Liem also pointed to CSA’s work on partnerships with school systems, high schools, historically Black colleges and universities, and other universities with strong performance programs to educate other theatremakers about the casting director position and collaborative process between casting directors and other creatives.

Vazquez meanwhile pointed to Broadway for Racial Justice’s nine-week training program for theatre professionals interested in casting. Vazquez is serving as one of the programs trainers alongside F. Binta Berry, Erica Hart, Christine Mckenna, Xavier Rubiano, Gama Valle, Danica Rodriguez, and Andrea Zee. This casting directive, announced in September, is aimed at providing the experience needed to begin working as a casting assistant in the business.

The hope is that, by putting out the “fire in the basement” that aptly describes the experience of those trying to enter the field, there will be a ripple effect as more diverse individuals begin to take the reins and bring their imaginations and visions to the artistic and casting processes. After all, the problem with a lack of diversity our our stages is not due to a lack of available or qualified talent. There are instead roadblocks between them and the stage, including the choice of what plays are produced and who directs them, of course, but also who is heading up the casting team. Vazquez hopes that the future has undergraduate and graduate programs jumping into the fray, both introducing new generations to this area of the field and offering up another path toward joining the casting director ranks.

“That is how we’re going to get more actors of color represented onstage,” Vazquez said. “That is how we’re going to be able to work with directors of color, who then do not have to negotiate with the white casting director who has not spent any time or energy building professional relationships with Black actors, with Latinx actors, with South Asian actors, with Filipino actors, or who does not have a nuanced understanding of how diaspora works within each of these ethnicities and races. So yes, I’m a huge advocate of, when we ask the question, ‘Where are the casting directors of color?’ we can point to a long, long list and we can say, ‘Here they are.’”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor at American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org