“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.”

—Orson Welles, as told to friend and fellow filmmaker Henry Jaglom

Ben Senneff and Steven Huynh had no idea where they were going when they pulled into the parking lot of Baldwin Wallace University’s Kleist Center for Art & Drama in Berea, Ohio, on a Thursday night last month. Their instructions were vague and felt slightly illicit: Get out of class early, head to the theatre with a full tank of gas, and await further instructions.

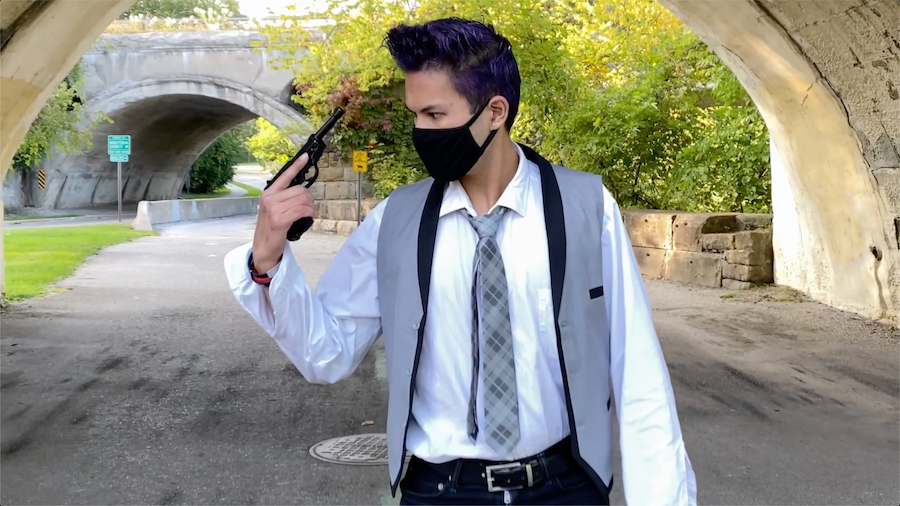

Oh, and they were to come in their costumes, which were a mash-up of classic—vests and ties and button-down shirts (think stuffy boarding school)—and contemporary, their hair styled in high pompadours and streaked with purple.

Both young actors had won the part of Moritz Stiefel, one of the doomed teens in Spring Awakening, the Tony-winning period-piece-cum-rock-musical by Steven Sater and Duncan Sheik. Victoria Bussert (she/her), head of BW’s musical theatre program, always double casts the big fall shows to give more students a shot at both the meaty roles and ensemble spots. This, the first virtual college production of Spring Awakening, streamed Nov. 19-22 through Music Theatre International, was no different. The show will have an encore performance online Dec. 17-19.

As Moritz 1 and 2, Senneff (he/him) and Huynh (he/him), along with their fellow cast members, had spent a peripatetic month and a half invading city parks and hidden graveyards—more than 40 locations throughout Northeast Ohio—to shoot B-roll for the school’s audacious project, which was to be part guerrilla film, part mother of all music videos. Still, this clandestine parking lot rendezvous was a first. Then again, not knowing where you’re going but trusting that it’ll all work out when you get there is an apt metaphor for staging a musical in the midst of a pandemic.

COVID-19 might have darkened theatres from Broadway to Berea, home to the small liberal arts college some 30 minutes outside of Cleveland, but that didn’t mean you had to stop making art. Victoria Bussert, “Vicky” to her students, isn’t one to let a worldwide plague stop her.

“I say this as the highest compliment possible—she’s one of the most stubborn people I know,” says Laura Berg (she/her), one of Bussert’s former students. “Theatres have shut down everywhere, and this woman is just like, ‘Fuck that! We’re doing a play, we’re doing theatre. Give me hoops—I will jump through them, but I will make it work.’”

Bussert’s program is known for its excellence and gutsy, radical innovation. Among its claims to fame are the first repertory productions of La Bohème and Rent; the world premiere of Lizzie, an all-female, punk/gmoth rock musical about the infamous accused ax murderess from Fall River, Mass.; and the academic premiere of Kinky Boots, which drew to BW Jerry Mitchell himself, the Tony-winning choreographer and director of Broadway’s original Boots.

But putting on a show—a musical, no less, one of the most collaborative of arts—as coronavirus cases spiked was like nothing BW had ever dared. Schools all over the country had canceled their live theatre productions, produced stripped-down Zoomsicals with actors trapped in “Brady Bunch” boxes, or moved their slate of shows to the spring in hopes that America would no longer be one giant hot zone by 2021. And who can blame them?

After all, what would a pandemic-era production look like, and how would people see it? How could you perform group numbers when unmasked group singing is verboten? What about kissing? And most importantly, how would you keep everyone safe?

“I don’t know,” Bussert admitted during a panel discussion on Facebook Live with heads of other music theatre programs in September. But she was going to figure it out. She owed it to her kids, especially seniors such as Senneff and Huynh, hungry for more experience before graduation and robbed of the chance to fill out their résumés with professional shows in Cleveland—a vibrant theatre scene boasting the largest performing arts complex outside of New York City’s Lincoln Center—before houses were shuttered in March to slow the spread of COVID-19.

By mid-October, six weeks into an eight-week production schedule, she’d jumped through plenty of hoops, some of them flaming—like having to contact the Berea police 15 minutes before rolling on any scenes involving a prop handgun to avert a real-life tragedy, something they never had to worry about when performing inside a theatre. (Imagine the 911 call: “There’s a boy with purple hair, in a mask, in the park, holding a gun.”)

But she’d seen enough footage to know the bold bid might just work. At the very least, they were having a hell of a good time. Choreographer Gregory Daniels (he/him) has taken to calling the process the “Spring Awakening roller coaster,” with its twists and turns and drops. “It’s been a wild, exciting ride,” he says. “For everybody.”

So when Bussert rolled up alongside Moritz 1 and 2 outside the Kleist Center in her red Kia Soul with music director Matthew Webb riding shotgun, she didn’t say a word. She just nodded at them from behind the wheel, then took off. “She just goes,” Huynh remembers. “There was no waiting for us.”

Twenty minutes into the journey to God-knows-where, Senneff wondered if they were traveling out of state. Their anxiety and excitement built as he read a stream of texts from Webb aloud: “When’s the last time you ate? Have you gotten a tetanus shot lately? Any fears of snakes or spiders? Do you know your blood type? Vicky wants to know if you ever dissected anything.”

By the time they arrived at the Rage Room in Akron 45 minutes later, they were so keyed up, they didn’t have to “act” when they picked up sledgehammers and bats and smashed their way through china and beer bottles and pulverized a printer. “Breaking shit is fun,” Senneff says, though his ears didn’t love it. But if there’s a better way to unleash pent-up adolescent fury, I’d like to know what it is.

Webb, who doubles as director of photography, put on a blue-shard-resistant moon suit and captured Moritz Squared demolishing everything in sight on an iPhone 11 Pro. It’s the same smartphone he used to shoot almost everything for the production, save a final, dramatic aerial shot courtesy of a drone. With five minutes to spare, he videoed each of the guys, slumped on the floor, exhausted, surrounded by broken glass. Alone with their destruction. “It was so desolate,” recalls Bussert.

Later, Webb would intercut the Rage Room sequences with Huynh and Senneff singing Moritz’s searing solo, “Don’t Do Sadness.” As devotees of the musical know, his words are a hollow boast. After failing out of school, Moritz is brutally punished by his father and, consumed by sadness, picks up a gun.

In Spring Awakening, based on Frank Wedekind’s 1891 play, teachers are cruel and oppressive; parents and priests are too. Even well intentioned adults get it all wrong. Moritz and his classmates are taught to repress their feelings and their sexual desire. Ignorance rules. “The original show is the tragedy of a community—a community that represses knowledge and keeps it from the children,” says Steven Sater, who wrote the book and lyrics for the musical, netting two of the show’s eight Tonys in 2007. “Whereas in our era, young people know everything.”

That still doesn’t insulate them from pain. While the story is set in 19th-century Germany, the driving alt-rock score links past to present. “The lesson implicit in the form was that no matter how much information you may have, you’re just as emotionally clueless, you’re just as emotionally vulnerable as you would have been in 1891,” says Sater. Bussert adds: “Teenagers now and teenagers 100 years ago are still experiencing the same hormones.”

Although Spring Awakening opened on Broadway nearly 14 years ago, it feels especially timely now, when even causal intimacy—the touch of a hand, a peck on the cheek—is forbidden. What’s more, says Sater, is the musical speaks to today’s politics in the loudest of voices. Thinking about what he’d say in an introduction for BW’s virtual production, he remembered Emma Goldman’s take on Wedekind’s brilliant original play. “I’m paraphrasing, but she wrote, ‘Has there ever been a more scathing indictment written about adulthood?’” Today, he adds, “the moral imbecility of adults and the tragedies of children that result from that” are all around us, says Sater, “tragedies we see beginning at the border but in all sorts of ways.”

As professional theatres struggle to find new forms to move forward—to literally survive—this college company might have pulled off one of the great COVID hacks of the year. The final price tag will come in at under $10,000—about $90,000 less than it cost to produce the dazzling college premiere of Kinky Boots there last fall.

The first day of shooting was Sept. 9 in Coe Lake Park near the BW campus. “I was so nervous!” Bussert recalls. “I’ve spent 30 years setting light cues with my own eyes.” Natural light filtered through a camera lens was something altogether new. Plus, how did you even start filming? She consulted YouTube to learn the parlance of moviemaking: “Stand by, rolling, action!”

Sleepy Berea, Ohio, didn’t know quite what to make of black-masked youth—boys in their vests and girls in long white skirts—cavorting through the trees. “Are you a Ukrainian dance troupe?” one woman asked. “I’ve always wanted to be in one.” Another asked: “Are you a lovely Amish wedding?”

On one early morning shoot, a lone fisherman watched the students as they carried a coffin they’d whipped up in the scene shop into a wooded area. “Uh-oh,” he said, grabbing his tackle and leaving quickly. When a cast of young women, costumed in ankle-length, optic-white skirts, shot a scene in the park under a tree on the night of a full moon, it prompted a post in a community Facebook group: “Was it a coven?”

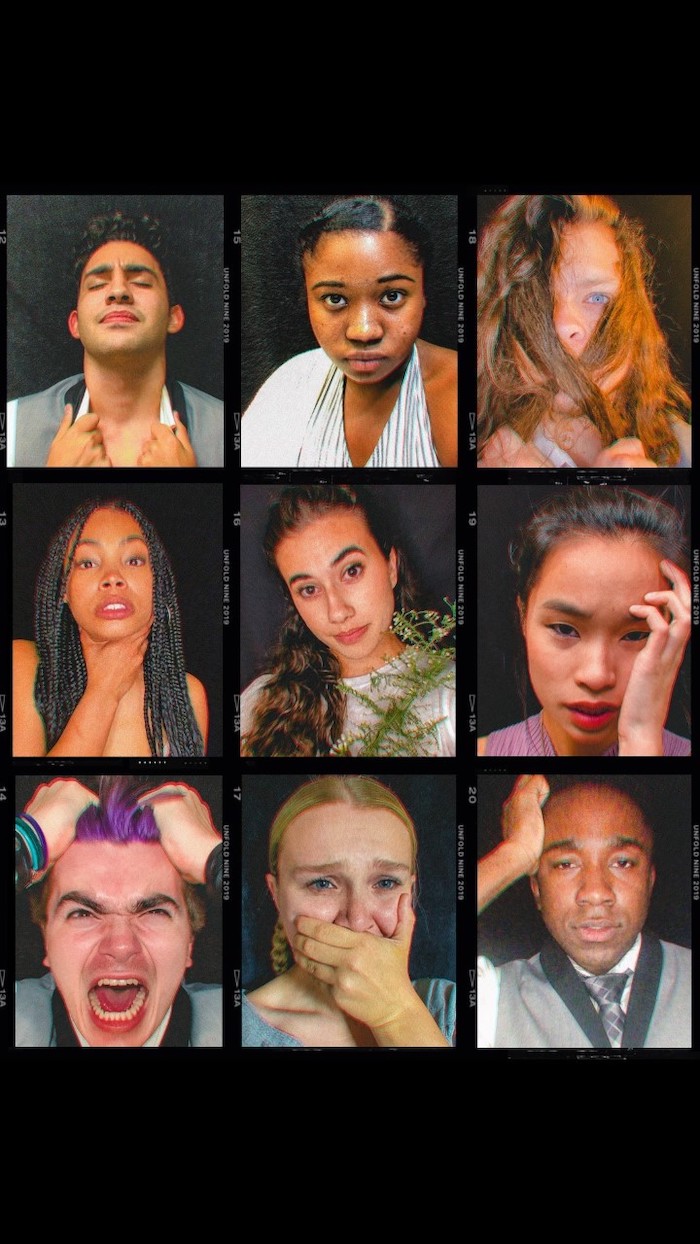

Bussert wasn’t just offering her students the rare chance to step back into the spotlight; she also hired some of her out-of-work grads, including Laura Berg, whose company, Cleveland’s Great Lakes Theater, had to scuttle its season this spring. Berg and husband Lynn, also an unemployed Great Lakes company member, were happy for their week-long Equity contract to play all the adult women and men in the virtual production, a multiplicity of characters with snortingly comic names (“Fraulein Knuppeldick,” “Headmaster Knochenbruch”). Ellis Dawson, (he/him) whose career took off like a bottle rocket after graduating from BW in 2016 (he landed the role of Genie in the Aladdin tour), is currently paying his New York rent with art photography, so Bussert recruited him to design the Spring Awakening poster.

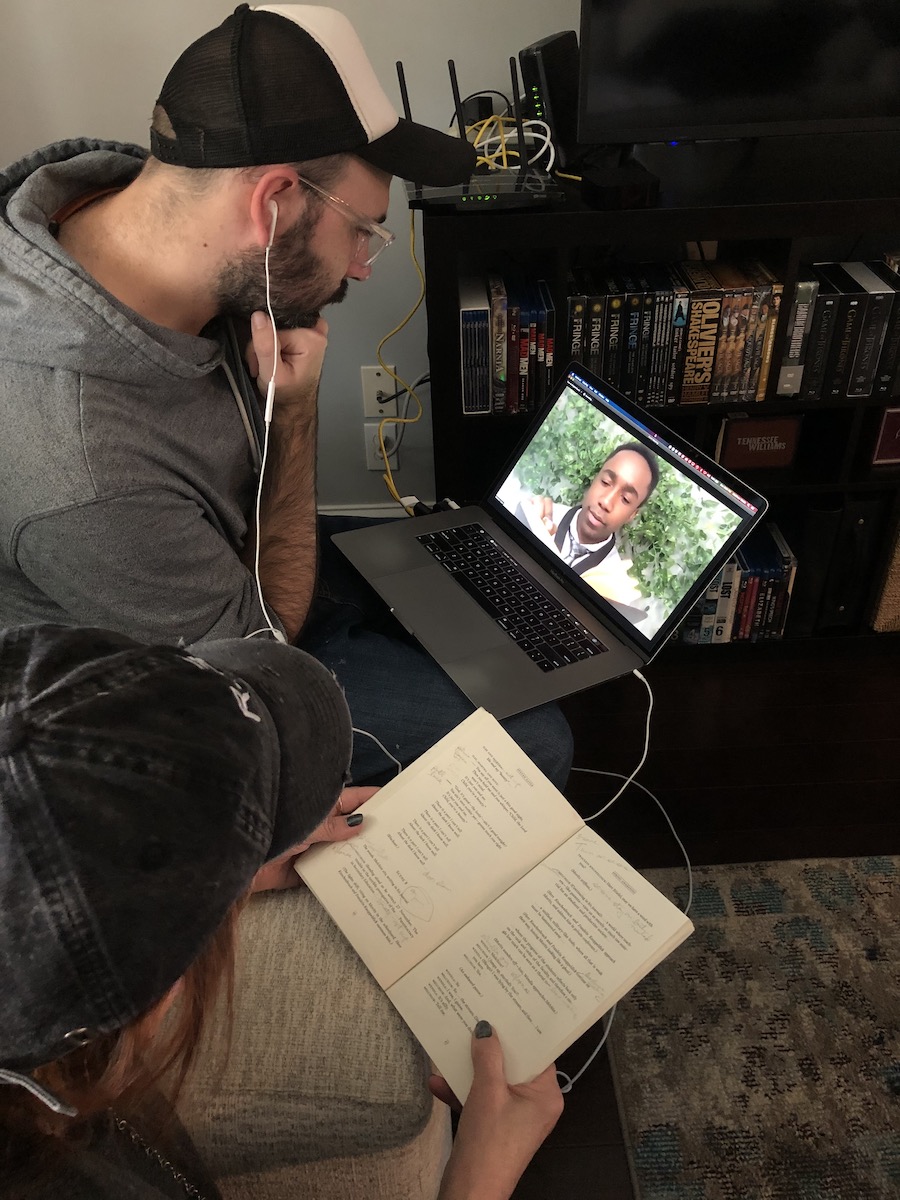

The man willing to do just about anything to get a shot—chasing after actors as they run through the woods or hanging from a catwalk dizzyingly high above the stage, or nearly backing off a cliff into Lake Erie to get a wide shot of students arranged on a dramatic sweep of tired concrete steps at sunset—is also one of Bussert’s “kids.” Webb graduated in ’08 and returned a decade later to assume the post of music director and assistant professor of musical theatre at his alma mater.

Sweetly unassuming and known for his perennial ballcaps and flip-flops, Webb, who’d never shot or edited digital footage before, is what Bussert calls the “secret sauce” of Spring Awakening. That’s because, in addition to his derring-do, he edits images rhythmically. “He feels every phrase,” says Bussert. Webb assembled the visuals and sound from a hodgepodge of disparate pieces and parts. He weaved together Zoom footage, location shots, animation, and more into a fast-moving, seamless, emotionally charged whole.

Another major element that Webb stirred into the digital brew are the student “confessionals.” To prevent the spread of the virus, students never sang together. Instead, they holed up in their home closets, taped a bath towel to the wall behind them and recorded themselves singing. They sent these “confessionals” to Webb, who mingled their voices using sound-mixing software. When Bussert saw and heard those first solo recordings, she was shocked at how good they were. Weaned on smartphones and Instagram and Snapchat, she realized her students are more natural and at ease in the virtual world than onstage.

“I’ve never seen anything better than these confessionals—it’s going to change the way I direct,” says Bussert. “The energy and the creativity that comes back is insane.”

The more people together in one space, the higher the risk, so Webb used recorded music in place of a live orchestra. The usual 10 to 14 kids on a stage crew were whittled down to Bussert and three stage managers, who schlepped props and costumes and scenery all over town (mostly tape and towels, if truth be told, but more on that in a moment).

Auditions were held via Zoom, and Greg Daniels taught dance combinations that way too, which mostly worked, despite the distractions. “The kids are in their dorm room or their bedroom, and the dog is walking through as they’re learning the choreography,” says Daniels.

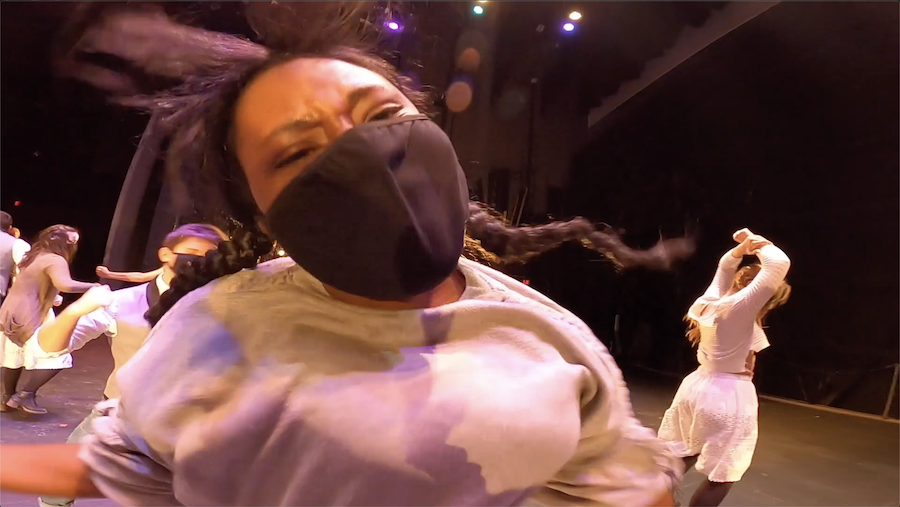

After a brief rehearsal in a nearby school gym, they moved onto a mainstage-turned-soundstage to space, then shoot the number. No one was ever without a mask. “Your eyes have to be telling us what we can’t see in your face,” Daniels reminded them. Because of concerns about poor air-flow quality in the theatre building, cast, crew, and creatives had to leave the space every 30 minutes and not return for another half hour. Bussert spent the time waiting for the space to “rest,” rehearsing scenes outside on the loading dock that would be shot the following day.

Famously, past productions of Spring Awakening did not shy from frank depictions of sexual exploration and discovery, the electricity of skin on skin. In the age of coronavirus, students and the choreographer had to keep their distance. “I literally touched no one to adjust anything for this production,” says Daniels. “And they could not touch each other,” he adds.

Despite these limitations, Daniels brought the heat: In one cheeky sequence, a conga line of dancers does one-handed backward push-ups, thrusting pelvises skyward while their mirror image is flipped and superimposed above them, creating a sort of coital kaleidoscope.

Scenes with dialog were also shot via Zoom, with all the attendant glitches and hitches, digital and otherwise. Cats scratched and yowled at closed doors; somebody’s internet always went out, or too many people in the house were online at the same time, causing the dreaded screen freeze.

They created a glossary of terms to deal with the realities of remote rehearsals. “Zoom-ography” (the order in which you turn on your laptop camera and appear on screen); “Space-bar-ography” (hitting mute when you aren’t speaking to minimize feedback); and “towel wrangling.” Every student had a pile of them—black towels and gray towels and colored towels and patterned towels that look like delicately patterned Victorian-era wallpaper on camera—as well as a good supply of packing tape, to counteract the tendency of towels to begin migrating down a wall mid-scene.

During a weekend shoot at the Bergs’ house in Cleveland, Bussert busily ironed a towel on a counter in the kitchen; Laura Berg shimmied into a red corset for a hot-for-piano-teacher fantasy sequence against a green screen, and Lynn Berg crouched on the floor of a nearby guest bathroom to deliver a fire-and-brimstone speech about the wages of sin, his nose inches from a stool covered with shimmering votive candles from IKEA. Matt Webb, sandwiched up against a wall and contorted into a yoga pose, operated his iPhone camera on a teeny tripod. “It is all glamor directing film,” Bussert quipped.

Their last day of shooting was in a graveyard at dusk on Halloween. Bussert had scouted four cemeteries before finding a lonely place filled with headstones from the 1800s, some so weathered that the names and dates had all but vanished. Webb wore a mask covered in spiderwebs for the occasion. Students arrived shivering, the two Wendlas wearing sweats under their filmy nightgowns. They were there to reshoot a scene in which a distraught Melchior is visited by two ghosts.

Bussert blamed herself for the need for a second go-’round because she’d tried spraying canned smoke to create a spookier mood—something that works well inside a theatre, where the mist hangs in the air, diffused by light. Outdoors it’s “too directional,” she said, and she was right—it looked very Ed Wood, like someone was standing off camera blasting away with a can of colored hairspray. She reviewed the revised scenes standing behind Webb, peering at his iPhone screen. They were haunting. It was a wrap.

The first video promo for Spring Awakening turned heads, not only for its raw artistry and headbanging hormonal energy, but also for a scene in which two of the actors playing Wendla and Melchior lean in for a kiss. The camera cuts away before their lips meet. Left unseen are the seconds leading up to that moment, when the students briefly removed their masks and held their breaths for a count of 10.

“No masks, no way,” one viewer grumbled in a post, after seeing it on the Music Theatre International website. Replied Bussert: “Nobody, NOBODY is unmasked unless they’re alone in their room or unless we’ve asked them to hold their breaths for 10 seconds. It just doesn’t happen.”

The success of the Baldwin Wallace Music Theater COVID-19 protocol is evident in the numbers. In eight weeks of shooting with 38 actors, three creatives and three stage managers, there have been 0 cases of coronavirus. “You can create real art today—you don’t have to say, ‘Oh, there’s a pandemic, we can’t make anything,’ ” Bussert said.

Fifty years from now when the young actors are grandparents, she said, “They’ll be showing their grandchildren this stuff.” Her eyes filled with tears. “It’s amazing to me that this record will exist, because we never have that in theatre.” Vicky’s “kids” will have this virtual Spring Awakening, “forever,” she says: a record of their youth, evidence that art can survive a plague, and proof that creativity is our best vaccination against despair.

Andrea Simakis (she/her) is an independent journalist in Cleveland and a frequent lecturer at Case Western Reserve University, where she teaches courses on criticism and narrative nonfiction writing. Her honors include a Nieman Fellowship, a Dart Award, and a National Headliner Award for her profile of Cleveland playwright Eric Coble as he shepherded his play The Velocity of Autumn to Broadway.

Spring Awakening is written by Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater. It is directed by Victoria Bussert, with music direction by Matthew Webb, choreography by Gregory Daniels, and casting by Colleen Longshaw Jackson.