How do we create queer community in the digital sphere?

Once it became clear back in March that it would be quite some time before we could gather, folks across fields, disciplines, and communities had to act quickly and creatively to find new ways to come together.

Right before quarantine, I had accepted the role of community programs coordinator for National Queer Theater’s Criminal Queerness Festival. I was thrilled to be spending the spring imagining ways to connect our plays and artists to LGBTQ+ immigrant communities in New York City. I was also thrilled to be out and proud for the first time in an LGBTQ+ artist network that reflected the diverse, intersectional identities I hadn’t held space with before.

Gathering is a sacred act for LGBTQ+ communities. We come from a lineage of elders who couldn’t gather at all without risk of arrest and criminal consequence, not to mention the years when our community gatherings were considered lethal during the AIDS epidemic. So in 2020, when our safe spaces—our community centers, bars, clubs and even theatre venues—closed indefinitely, much of our community was left, once again, in isolation and fear.

With COVID comes an unfortunate reminder of how uniquely the LGBTQ+ community is affected by crises. LGBTQ people and communities are disproportionately at risk for COVID, a fact linked to historical systems of oppression. Our community is often at higher risk for chronic illness, including HIV/AIDS, and is systemically barred from full access to healthcare. Worse, our elders were already likely to be isolated and lacking community before COVID, a problem that has only been exacerbated since quarantine and social distancing measures have been put in place. In such an isolating time, creating digital spaces that are accessible to all LGBTQ+ communities is more vital than ever.

My opportunity to begin investigating what those virtual spaces could be came when I was invited to facilitate the LGBTQ+ Affinity Space at TCG’s Convergence, the first portion of their virtual national conference this year. While TCG has held many national conferences in the past, this was the first time it was done digitally. With that came new opportunities. For the first time, this session could be accessed from anywhere in the country, free of charge. This opened up accessibility to all career levels: emerging artists, artists in their early/mid career, and veterans in our field. Additionally, it allowed for more regional diversity and access for those who may not have had the means to pay to fly to another state to gather in person.

In all the roles I’ve held in theatre spaces, I am always thinking about who is in the room and who isn’t in the room, and why that is. When I facilitate, there are ways I get a sense of this through exercises with the collective. This practice looks different on Zoom. People can’t walk around a space. Introductions don’t happen on calls of over 10 participants. Participants can come and go much more freely.

I’m a timeline-oriented person. My favorite activity in facilitated sessions in which I’m a participant is creating a timeline together. This allows different people to see and show where they were at during different times in their lives and the moments they intersect with history. It’s a good way to see who is in the room—and, if you’re familiar with history, a good way to see who is left out.

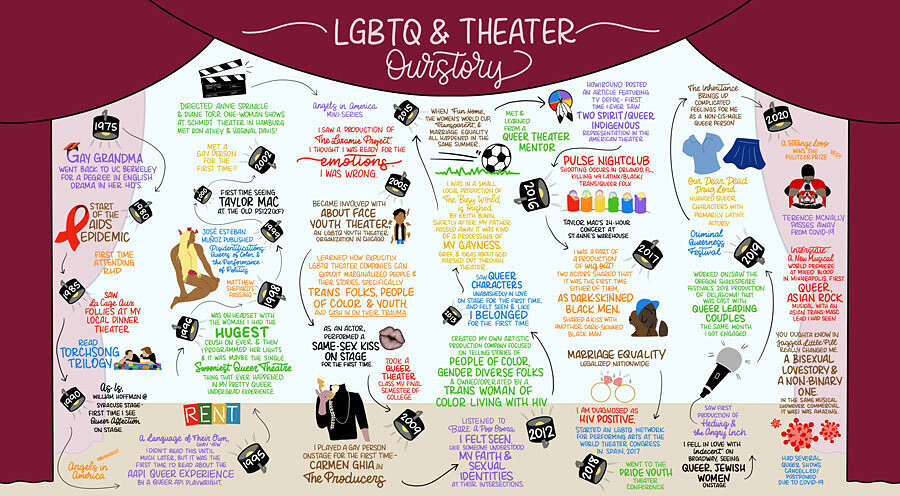

So that’s what we did in the LGBTQ+ Affinity Space at TCG. On a shared Google doc, I introduced a timeline ranging from 1975 to 2020. I teed up the activity by talking about my own background and timeline on my journey to LGBTQ+ theatre—a personal history informed by characters like Kurt Hummel and Santana Lopez on Glee, seeing Rent for the first time, collaborating with queer mentors, and working at National Queer Theater.

I then asked participants to do the same on the doc, not only listing significant dates relating to LGBTQ+ theatre representation and history, but also significant moments in their own lives and in the lives of LGBTQ+ people they love.

The energetic outcome in the virtual space was electric. “I found it really beautiful just to actually see, [the Google doc] live populate,” says New York-based director, cultural worker, and session attendee Sivan Battat (she/they). “That was one of the coolest things about it. To be looking at a different moment of it and see it just sort of live-populated, I could feel the energy of something like [60] queer theatre practitioners adding their ideas. You’d add something and then you’d scroll up and someone would have just added that there as well or somewhere else. There was kind of a beauty in dialogue and people commenting on each other’s additions.”

The sheet became a cacophony of emotional memories. Answers ranged from personal experiences to first interactions with queer media to just meeting someone who was queer for the first time. But even within this celebratory space, the activity, and the session, also laid out visually how much the arc of queer theatre history has been fragmented by loss. The LGBTQ+ community is missing “elders.” For every artistic reference (Angels in America, Taylor Mac), there was also tragedy, like the Pulse Nightclub shooting and the AIDs pandemic. The oppressive violence faced by so many queer people and communities makes finding other LGBTQ+ people to be in community with difficult, even in theatre.

Even so, what emerged in this session, and what many others are currently discovering, were the ways in which virtual space, when created with a community-centered lens, can actually grow community by inviting more people into the spaces where we gather. The importance of community and representation across identities and disciplines was highlighted by attendees as a big takeaway from the space. “I don’t often find other technical directors in LGBTQ spaces,” says Minnesota-based technical director and session attendee Frankie Charles (he/him). “I struggle with burnout a lot. I have felt very isolated being trans in a scene shop or a classroom. But seeing so many amazing people in the affinity space reminds me that I’m not alone.”

While many theatres and theatre practitioners have also engaged with the concept of broadening their audiences in new ways during COVID, being able to reach more people with queer art is particularly important, given how powerful representation can be for those with marginalized identities. Queer people in small regional towns throughout the country shouldn’t have to wait until they have the means to “move to the city” to discover larger communities of LGBTQ+ people and more accepting environments.

The sense of togetherness drawn from representation can also extend queer American theatre to global audiences now. Says Battat, “This play I directed for National Queer Theater, She He Me, by Amahl Raphael Khouri, was supposed to happen at Dixon Place. We ended up doing it on Zoom and we had viewership from across the Arab world. There were queer Arab people and queer Middle Eastern people tuning in from all over. I got messages from some of these people saying, ‘I’ve never seen these stories represented. I’ve never seen my story. Thank you so much for sharing this.’ It was very, very exciting to me that we [went] beyond the scope of Dixon Place at that moment.”

Another positive outcome of remote programming: the opportunities it opens for an array of diverse queer representation, especially as it relates to casting those with intersectional identities. New York-based director, playwright, and cultural consultant Kareem Fahmy (he/him) has experienced this firsthand. “I [had] a reading of a very queer play with an all queer cast,” he said. “We set out a sort of challenge to the producers to say that we want to prioritize casting queer people of color in all of the roles. What would happen in a normal setting, depending on where we were geographically, even in New York, you might actually hit up against some barriers where you can’t necessarily fill all of those roles exactly as you want: racially specific and queer-specific and age-specific too. But with COVID, we had access to actors anywhere.”

Several other LGBTQ theatres are also embracing this opportunity for innovating new and inclusive virtual programming to showcase diverse, queer narratives to a broader audience. This November, The Theater Offensive is centering LGBTQ community youth with their Beyond The Stage virtual benefit concert, which will serve as both a night of performances and a fundraiser for True Colors: OUT Youth Theater. About Face Theater’s new upcoming virtual festival, titled Kickback, will feature a series of commissioned plays and performances from a cohort of Black LGBTQ+ artists. This world premiere virtual festival in December will be free and open to the public, and will showcase the intersectional experience of artists who are both Black and queer. Meanwhile, Ring of Keys, which already boasts a virtual international reach through their online directory of queer women and TGNC artists, are in the beginning stages of reimagining what their annual Queering the Canon Concert Series could look like in the spring of 2021. These are just a few of the exciting new programs and events coming up that find queer theatres and artists creatively navigating the constraints of the pandemic to create art that is meaningful, community-building, and future-facing.

As an LGBTQ+ history month in the midst of a global pandemic comes to a close, and the ominous uncertainty of November’s presidential election looms ever closer, it’s important to remember that memory is privilege. Remember how easy it is to forget those who have not historically been prioritized in America and American theatre. Supporting queer art doesn’t begin or end with your carefully diversified show lineup or self-proclaimed groundbreaking casting of a queer lead character or actor, or even simply supporting the above-mentioned queer theatre organizations. As illustrated in the “Ourstory” activity, the national and global reality of LGBTQ+ rights cannot be divorced from queer theatre and its practitioners. To support queer art, you must also support the lives and rights of queer people and queer artists. As we enter the next decade in an ever-going “Ourstory,” let this one be one of discovery, safety, visibility, and celebration for queer artists.

Bri Ng Schwartz (she/her) is an arts administrator and facilitator with a focus in community engagement programming. She is the outreach associate at Pan Asian Repertory Theatre and was the community programs coordinator for National Queer Theater’s Criminal Queerness Festival this past summer.

Ciara Diane (she/her) is a New York-based freelance writer, poet, performer, playwright, and arts administrator. She is a Sagittarius, intersectional feminist/womanist, Afrofuturist, devout believer in Black liberation, and, above all, a storytelling experience.