As we enter the eighth month of the pandemic, with no vaccine or stimulus deal in sight, most American theatre companies have scotched their initial plans for the current season, producing plays online or not at all and hanging their hopes on a robust reopening sometime in 2021. But with additional federal and state funding and the ongoing generosity of donors up in the air, how long can companies hold on before they are forced to shut their doors for good?

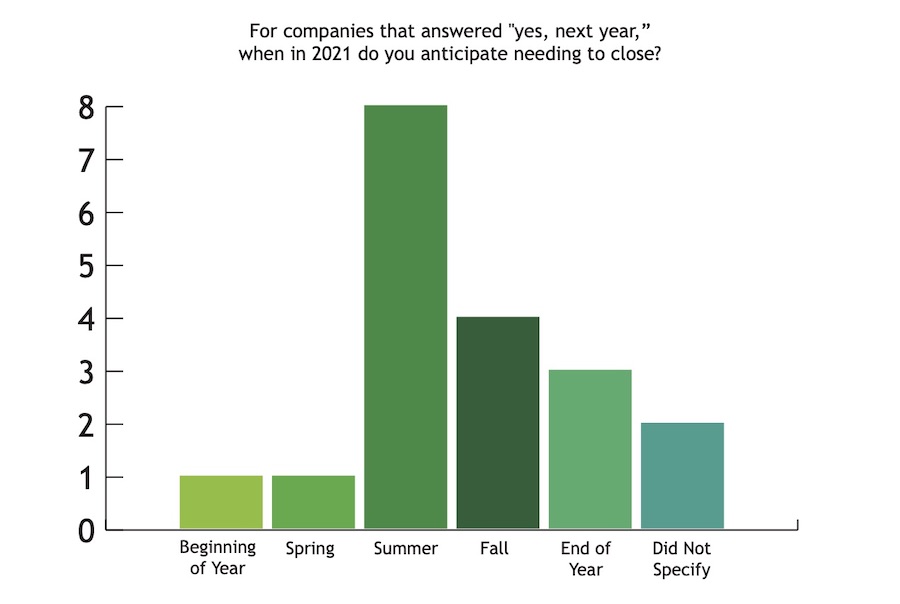

In search of answers, I sent a survey in mid-September to hundreds of managing and financial directors of Actors’ Equity Association-affiliated theatres across the country, asking how COVID and its attendant economic spiral have impacted their company’s financial health. By the end of the month, I had received 60 responses from companies in 27 states and Washington, D.C., their operating budgets ranging from under $200,000 a year to nearly $90 million. The results paint a vivid picture of life as an American theatre company under COVID. It is by no means a uniform portrait: While some companies have actually seen their coffers swell in the past six months, almost a third of the 60 companies surveyed will be forced to consider closure some time in 2021 if restrictions on gatherings persist, without additional government support. Another six companies anticipate needing to close in 2022 or 2023 given these same conditions, and seven are unsure if closure will be necessary in the near future—as one company succinctly put it: “??” Only 23 out of 60 are confident that they will not need to close before the pandemic runs its course. You read that correctly: Almost as many theatres surveyed think they’ll need to close next year as think they will not need to consider closing at all.

These numbers are shocking if not surprising. But can we trust them?

While it is certainly possible that the companies that responded to this survey were in some way self-selecting and do not reflect the overall national outlook, the respondents were fairly representative, from urban and rural markets in all parts of the country, operating under a wide range of Equity agreements, from dinner theatre to LORT B.

Unfortunately, it makes sense to accept that these numbers are at least somewhat indicative of the industry at large. And if things don’t change on the lockdown or relief front, we are likely to see rolling theatre closures throughout 2021. If arts organizations do not receive additional stimulus money, and/or if theatregoers are not able to be vaccinated to a degree that will allow Equity, the CDC, and local authorities to approve the resumption of live performances at a seating capacity that yields a profit, they will have little choice.

That last item is a big if. In a recent and widely publicized interview with Jennifer Garner, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci warned that mask-free, at-capacity playgoing may not resume until late next year—and that’s assuming a successful vaccine rollout.

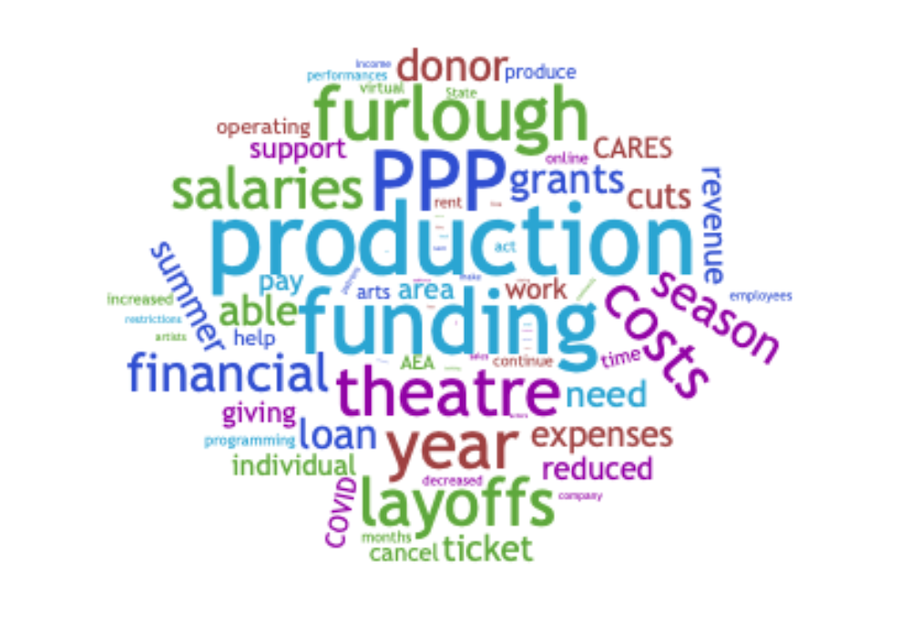

We are also likely to see significant staffing and budget cuts from companies that are able to stay open. In an effort to stay afloat, most companies have already instituted drastic cost-saving measures. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that live production has come to a grinding halt almost everywhere, half of all companies who responded to the survey have already furloughed staff or cut pay, and 24 out of 60 have laid off at least one employee. There is significant overlap here; one quarter have both laid off staff and handed down furloughs or pay cuts. Many envision another round of difficult cost-cutting, whether or not they forecast eventual closure: 20 companies anticipate future layoffs or furloughs if the situation does not change. Three responses went further, suggesting that their organizations might need to “vastly restructure”—become a host venue, perhaps, and cease producing themselves—in an attempt to avoid closure.

One worrying sign: Most companies surveyed are still relying on a burst of government and individual goodwill from earlier this year to help carry them through 2020. Three-fourths of companies mentioned the CARES Act and its grant and loan programs for small businesses, the PPP and EIDL, as helpful in insulating them from COVID’s worst effects, and 27 companies, many fresh off emergency fundraising drives, reported increased individual giving or loyal donors as financial lifelines during the early months of the pandemic (only about 1 in 6 reported decreased giving; there seems to be no observable predictor for whether a theatre’s donors responded in one or the other direction).

What will happen when these unusual influxes of capital are gone? Congress appears unlikely to reach another stimulus deal before the election; the political world after Nov. 3 is a complete unknown; states are strapped for cash; and our recovery might well be L-shaped, which would likely negatively impact corporate giving and government support. One executive director in Missouri notes that their company has “not been able to factor in the impact a lingering financial recession will have on discretionary spending.” Some survey respondents privately predict that the desire and ability of individual donors to respond to future fundraising pushes will likewise wane in direct proportion to the length of the crisis. As one managing director in Ohio puts it, “It is unclear how long our donors will support a theatre that is not performing, but it won’t be forever.”

“It is unclear how long our donors will support a theatre that is not performing, but it won’t be forever.”

Still, some theatre companies are weathering the storm relatively well, with others poised to emerge completely unscathed. While it might stand to reason that the companies with the largest operating budgets would fare better than mid-sized and smaller outfits, this does not appear to always be the case. One general manager of a financially comfortable LORT B theatre reports that, thanks to the company’s healthy endowment, “If we needed to fold because of COVID, I think the country and world would be in a very, very bad place.” An executive producer of another LORT B theatre that recently undertook an expensive building project tells a different story: They “need to produce” by the middle of 2021, and if this is not possible, the company “will face very serious impacts.”

Theatres that are doing well fall into one of three categories: companies with endowments and healthy cash reserves that were in good financial health pre-pandemic and did not recently take on significant financial risk or burden (i.e., purchasing or renovating a new space); companies tied to universities that have pledged their continued support; and companies that have little to no overhead. Theatres in the third category tend to be theatres operating on a shoestring budget or on a seasonal basis. With no permanent brick-and-mortar home and thus no rent or mortgage payments and few full-time staff, they can “hibernate” relatively easily by not spending money to hire show-specific employees or rent unnecessary space and costumes. One such company even found itself comfortably in the black this year, noting that because of donors’ recent generosity, as one of its leaders put it, “When we are not producing, we actually show a profit.” Theatres that do not fall into one of the above three categories generally see closure somewhere on their horizon.

Where does Actors’ Equity fit into the picture? Equity has only given the green light for a handful of live productions since the advent of COVID. Is this an unfortunate but necessary reflection of our public health reality, or could Equity be doing more to sustain the industry? In May, Equity released a memo outlining their “Four Core Principles Needed to Support Safe and Healthy Theatre Productions,” and encouraged theatres to submit individual safety plans for proactive approval by Equity in case local public health conditions rise to meet the union’s approval for producing in a given county.

Surveyed companies were divided in their take on these four principles, but even those that agreed with the requirements themselves had complaints about a perceived lack of transparency, communication, and specificity on the part of the union. More than half did not agree with the requirements at all, labeling them unreasonably strict, broad, inflexible, and vague, with several companies seeing Equity itself as the main barrier to resuming normal operations. Ten percent of companies surveyed have either already severed their relationship with Equity or are considering doing so in the near future, due to financial hardship and disagreement with union policies. It is unclear whether their existing contracts with Equity grant them official permission to do this or not, and whether theatres intend this as a temporary emergency measure or a permanent change in operations.

Also relevant to the financial well-being of theatres is Equity’s rapidly escalating turf war with its sister union, SAG-AFTRA, over jurisdiction rights for streaming productions. With the dispute as yet unsettled, 2020 has been akin to a Virtual Theatre Wild West, with some companies opting to contract with SAG, others sticking with Equity, some forgoing union contracts altogether, and some ultimately opting not to produce due to financing difficulties. Many union members and theatres have expressed frustration with the virtual contracts put forth by Equity, seeing them as prohibitively expensive for companies, with others applauding Equity’s push for higher wages and jobs for stage managers. In any case, it remains in significant doubt whether a theatre in a precarious financial position can be sustained or saved by revenue from virtual productions alone, no matter which union issues their contracts.

For some companies, union and government-driven restrictions aren’t the driving force preventing them from putting butts in seats. Citing an older and public-health-conscious audience base disproportionately vulnerable to the virus, one D.C. board president wondered, “Even if we were to reopen, will our audience return?” The executive director of a midsized Philadelphia theatre postulated that “only widespread dissemination of a vaccine,” not a relaxation of Equity or governmental restrictions alone, would “persuade the well-educated older patrons to return to theatres and concert halls.” Some expressed anxiety about whether audiences would return even after a vaccine is widely available, with a small Missouri company, worried about the possibility of a long-running recession, also listing “whether audiences will hold a lingering mistrust of indoor theatre activities beyond the end of the pandemic crisis” as an ongoing concern. More than one survey respondent described the specter of COVID as an existential shadow with a long reach.

Faced with the data this survey reveals, more questions than answers emerge. One question, though, remains easily and painfully answerable: Restriction disagreements aside, what can be done to prevent so many closures, absent an imminent vaccine? Answer: money. Response upon survey response called on the federal government to bail out the theatre industry in the absence of a coherent and effective response to the virus itself, arguing that theatre has inherent value, and also pointing to statistics which show that every dollar invested in the arts yields an eightfold return. Though Equity has partnered with other performing arts unions to lobby Congress in search of financial relief, their Save Live Events Now campaign has been overshadowed by the higher-profile Save Our Stages Act already in the pipeline. Co-sponsored by Chuck Schumer and championed by the likes of Miley Cyrus and Budweiser, Save Our Stages would earmark money to ailing performance venues, favoring for-profit companies and institutions.

But even Save Our Stages has little chance of passing in the current political environment. If Congress won’t bail out the airlines, how likely is it to bail out the arts? In this chaotic and desperate political climate, the theatre industry’s disempowered position has never been more keenly felt. Perhaps our best hope is to vote in November for national and state-level leadership that will act swiftly and decisively on its behalf.

One response in particular encapsulated theatre companies’ collective cry to anyone who will listen—governments, patrons, the universe: “Fix this please.”

Rosie Brownlow-Calkin (she/her) is an Equity actor and assistant professor of theatre at the University of Nevada, Reno.

An earlier version of this story erroneously stated that nonprofits would not be eligible for relief if the Save Our Stages bill passes.