“It’s not about standing still and becoming safe. If anybody wants to keep creating they have to be about change.” Miles Davis’s words have never been more prescient.

As we all stand ready to truly embrace a brave new world of living, communicating, and experiencing humanity like never before, we the creators, producers, and purveyors of the theatrical medium must evolve. A new paradigm of creativity is upon us, and we must abandon what used to be and accept the gift of what is now.

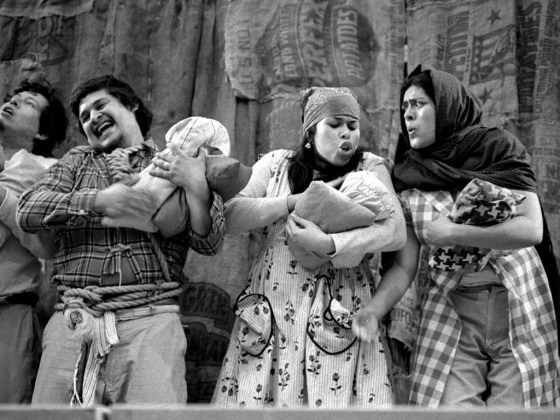

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we lost to cancer the physical manifestation of Diane Rodriguez—a fierce artist and champion of the theatre, hyper-collaboration, and women and emerging leaders of color. Her 47-year career started with El Teatro Campesino and the farm worker’s movement for justice, and it never stopped. This critical experience inspired and informed her work always. It is Diane’s voice which lingers in many of us and will continue to do so for generations—such was her impact on our field.

We are a small group of Diane’s family and friends who supported her throughout her two-year diagnosis, affectionately self-named Team Diane, and we continue to come together to ensure her legacy lives on. We have worked with Theatre Communications Group and American Theatre magazine to publish this piece. What you will read below are words Diane penned in the fall of 2019, before the depth and devastation of the pandemic had manifested worldwide. Before the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. Before the long overdue publication of We See You White American Theater. Before the world rose up to declare, with one voice, that indeed, Black Lives Matter—this essay was composed before all that.

To some, Diane’s analysis may be provocative and controversial; to others her words will serve as a battle cry for the possible. Diane’s thinking was on the precipice of a conversation that is mission-critical to the future of American theatre. What better time than now to reevaluate who we can be in this new, vibrant, and uncharted theatrical landscape? Let’s work together to build a much brighter and equitable future.

—Team Diane

For years, in the political jargon of Mexican American activist Baby Boomers (better known as Chicanos), I and my colleagues have used the word “decolonize” to define both our goal and the obstacles in the way of achieving it. So when, last fall, I saw a story in The New York Times about a protest staged by the activist group Decolonize This Place at the Whitney Museum, it drew my attention. The headline read, “New Scrutiny of Museum Boards Takes Aim at the World of Wealth and Status.” As producer and director at a nonprofit theatre for nearly 25 years (Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles), I saw firsthand that the nonprofit model is built on the patronage of the wealthy.

The New York protest had a specific target: outing a longtime trustee and benefactor, Warren B. Kanders, over reports that his company produced tear gas used on migrants on our border with Mexico. The protesters’ method of raising awareness was to stage an old-school 1960s protest by clamoring together in the lobby of the Whitney Museum. Crucially, they also got support from around 100 museum staff members, who signed a letter saying they felt “uncomfortable in our positions” given the news of Kanders’s business.

My takeaway: It took both an external protest and internal staff pushback to call out the problematic relationship between a large mainstream institution and a single board member. The message was clear: While public-facing artistic programs at many institutions are rightly under scrutiny for lack of equity and diversity, there must be a similar sense of social responsibility and accountability for the boards of these same institutions.

Clearly nonprofits in the U.S. depend on individual giving to survive. And while the protesters in this case did not intend to destroy an organization for accepting money from a questionable source, losing the generosity of someone like Kanders—who resigned from the museum’s board as a result of the protests—could shake the financial foundations of any organization.

In the Boardroom Where It Happens from Theatre Communications Group on Vimeo.

The 501(c) (3) section of the federal tax code was a mid-20th-century construct, first created in 1954 and reformed in 1969 during the Johnson administration. It set up a way for civic organizations centered on “a greater good principle” to function as public charities, with funds and programs to be overseen by an elected board of directors. Realistically, if that “greater good principle” is not fervently adhered to, one must wonder why both the philanthropic and the nonprofit arts and culture sector can withhold millions of dollars of taxes from the overall societal “greater good” without delivering services to all communities—not just those of privilege. This tax status enabled the newly formed regional theatres of the ’60s to receive certain tax exemptions and to solicit funds, offering their donors tax deductions on their contributions.

Innovating beyond or even within the prescribed nonprofit board model has in recent years proven elusive. I’ve heard Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, suggest that we solicit new board members who can bring in “other assets.” This concept has been around for years, and is often specifically designed to target potential board members of color. But I have seen firsthand how this well-meaning effort can create a class system on boards. If you have a board member who has been recruited for “other resources”—i.e., who is not required to “give or get” financial assets, as other board members are—it becomes all too likely that this new board member will be treated like the “diversity hire” or considered to be filling an “affirmative action slot.” The gesture can work if you are lucky enough to have a celebrity of color, or an individual who is highly respected for their intellectual prowess and connections. But unless other board members and leaders are educated about new principles and values, changing the makeup of a board to create an equitable and socially responsible cohesion is a monumental challenge, not merely a cosmetic effort.

It’s also an urgent mandate. Nonprofit theatres have a responsibility under the law to adhere to the “greater good principle.” If we simply replicate the economic and social hierarchies of the for-profit world, why are we tax-exempt at all? In its purest form, the concept of the wealthy giving back for the greater good is obviously right and true. But this ideal has been corrupted. Now it seems philanthropy must be rewarded. It’s not enough for many donors to stand back and see how their altruistic gifts are being used. Instead, in exchange for their generosity, donors now expect and receive numerous perks: a standing in social circles, exclusive donor rooms for pre-show receptions, private opening night parties with access to artists, insider trips to London or New York to see the latest artistic offerings, a donor staff concierge who helps them buy tickets to shows around town, and more.

Make no mistake—their generosity has tangible benefits for the rest of us. But why not create a vision of philanthropy that is not rewarded with one-percent elitism that keeps the elite in their own separate area, but instead is in service of a democratic approach? Indeed, I don’t understand why, if we want to bring new audiences into our theatres, we don’t offer perks to individuals who have never passed through our doors before. Why not treat first-time audiences as magnificently as we do donors and members so they might return to us?

The task of changing the culture around a theatre’s board and philanthropic efforts falls, I believe, within the job descriptions of both the artistic director and executive leadership. Artistic programming isn’t just what’s onstage, after all; it is also the key to changing board culture and values. Arts administration scholar Diane Ragsdale, in a talk she titled “The Changing Face of Arts Engagement,” given at the Stratford Festival Forum in 2019, noted that we are “moving away from the colonial ‘democratization of culture’ toward what some would call a ‘democratic culture approach.’” Though these two concepts sound so close as to be interchangeable, they are in fact quite distinct. For everyone to have access to a world-class production of Shakespeare, she noted, is an example of the “democratization of culture.” Culture in this approach refers to the existing “elite” culture.

On the other hand, Ragsdale wrote, “A democratic culture is about cultural equity. It suggests that there is no pre-ordained artistic hierarchy that automatically places works made by ‘professionals’ above works made by ‘amateurs’; works that are improvised; works performed in a gorgeous facility overlooking a body of water over works performed in the community center, the prison, the school or on the streets; works by dead or living white men over…basically everyone else.”

I would certainly not advocate for everything in a theatre’s season to be performed by “amateurs” or to be site-specific. What is important, though, is the dismantling of the artistic hierarchy that has plagued our field for decades, and which exalts the works of dead (and living) white men over work by people of color. I believe that regional theatres are slowly making their way toward diversifying their offerings, while Broadway is all too aptly named the Great White Way.

In tandem with this racialized hierarchy is a resistance to changing modes of making work. But we who work with theatre artists who are challenging aesthetics and creating new modes of making work know that ensemble creations, work made collectively by collaborators, and non-linear work are just as impactful as traditional plays when contextualized and experienced in the right setting.

We all have the need, and the right, to tell our own stories. In exchange for that right we agree to hear the stories of others. This value should be shared in every artistic medium. Our boards need to wrap themselves around this concept. The work of Marisela Treviño Orta and Tarell Alvin McCraney is just as important as that of Tracy Letts. The work of Rude Mechs is just as valuable as work by Samuel Beckett—perhaps more so, as Rude Mechs are living artists tackling current issues.

In 2019 the theatre field saw leadership transitions at many large mainstream organizations, and this has been widely noted as a monumental victory. And indeed it is a victorious step for our field, as this transition resulted in new leaders of color taking over important longstanding theatres: Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Long Wharf Theatre, Baltimore Center Stage, Repertory Theatre of St. Louis, Actors Theatre of Louisville, Woolly Mammoth in Washington, DC., and TheatreWorks in Palo Alto.

What is remarkable about this new generation of leaders is not just that they are people of color but that they bring with them values of social justice, social equity, and appreciation for work by people of color, as well as new forms of theatremaking. This creates a two-fold challenge for traditional boards. One is accepting fully and deeply the challenge of creating true social equity; the second is accepting forms of theatre aside from the well-made play to entice first-time audience members to our theatres (and away from entertainment options that they can comfortably stream in their home).

Jacob Padrón is the new artistic director of Long Wharf Theatre. I’ve known Jacob and his family for more than 35 years, as we all hail from a small town, San Juan Bautista, on the central coast of California. Recently his theatre posted a job search for the “director of artistic partnerships and innovation,” with pointed social justice language that was like none I had ever seen in a job description from a League of Resident Theatre/LORT member. It read: “The director will be charged with building new collaborative models that will allow…collective resource-sharing and dismantle the structures that have historically limited many artists from being produced at our most visible theatres. The director will have an insatiable appetite to defy the status quo, grounded in the values of anti-racism and anti-oppression. They will lead with joy, rigor, and curiosity.” It almost reads like something from the website of Decolonize This Place.

At the LORT theatre where I worked, I definitely had an “insatiable appetite to defy the status quo.” But I was not the leader of the theatre, and those words were not in my job description. I was associate artistic director, and before that associate producer. But at Long Wharf, the artistic director is embracing this language and pushing for a democratic culture. Among the challenges Jacob and his like-minded colleagues will face in leading this charge will be to encourage their boards of directors to buy into the new values they are expounding. If they don’t get full board buy-in, there will continue to be a great and damaging contrast between these new leaders’ social-justice intentions and the expectations of privileged board members who continue to see their theatres as “elite culture” purveyors.

If we want our theatres to remain vital to our communities, we have to redefine philanthropy in terms of a larger mission of cultural equity. We must recruit and keep board members who understand this value as one that is urgent for the well-being not only of our artform but of our country. Furthermore, if board members are given the privilege of choosing new artistic leadership, they must not only commit to understanding and supporting the values of the new leader, but also to knowing more about current trends in the theatre, from aesthetics to audience engagement, and more. We urgently need board education. That will only happen if our artistic directors and their staff dream big, and follow through.

Last fall Charles McNulty, the Los Angeles Times theatre critic, wrote an article that gave an outside critical opinion of the shortcomings of the theatre I used to work for. “A radical rethinking of artistic vision requires an openness to the possibilities of new management structures,” he wrote. This is a truth that the new generation of leaders must face. They may have ambitious plans to change programming. But what are their plans to change the values of the board members who approve their budgets? They may have innovative programming ideas, but do they have similarly innovative plans for their theatres’ management structure? The danger is that if risky programming falters—and sometimes it does, at least at first—theatre boards who are insufficiently invested in the leader’s vision may be tempted to restrain rather than support it, and to refuse to take further risks.

I continue to have hope. With more artistic leadership of color and more women in positions to greenlight projects, we are undoubtedly entering a new phase for the American theatre. But if our board structure and its values stay the same, we will be sadly left behind. The potential for a new democratic culture that erases hierarchy and privilege could be monumental—a game changer. With the obsolete 20th-century nonprofit theatre paradigm under new scrutiny, all our artistic leaders must be on the alert to transform our theatres into places where all of us can meet under one roof and enjoy the voices of many. Can we transform our boards into supporters of Ragsdale’s description of a “democratic culture” for theatre? Can we convince them that philanthropy is not about gaining more privilege, but instead about creating cultural cohesion in a country that arguably has never really embraced this concept, and these days seems to be sorely losing it?

Theatres across the country may depend on the wealthy to keep our doors open. But art is not charity. People of color are not a charity. We are joined in a common cause, so let’s bring down the walls between wealthy patrons and the rest of us, between the so-called gatekeepers and the audience. Together we can build and sustain cultural centers that welcome us all.

Diane Rodriguez worked at Center Theatre Group as a producer and associate artistic director from 1995-2019. She got her start with El Teatro Campesino in the 1970s. She was chair of the board of TCG from 2013-2016.