The following is one of the forewords to Mad Clot on a Holy Bone: Memories of a Psychotic Theater, a new collection of plays by Asher Hartman.

Upon walking into my first Asher Hartman play, See What Love the Father Has Given Us, in 2012, I was guided down a dark hallway by a kind and glamorous drag queen (Marcus Kuiland-Nazario) and into a facsimile of the break room at a big box store, where, after offering us a taste of whisky, Joe Seely and Jasmine Orpilla launched into a mating dance of biblical proportions. We were seated no more than a foot away from the actors, and I spent the first few minutes of the performance in a panic that I might be asked to participate. But it quickly became apparent that this was not that kind of play. The Gawdafful National Theater held me close, but not that close. As Hartman (he/him) describes it, I was acknowledged as an audience member, not a participant—a nod he frequently makes to the structural antagonism that always exists between actors and audience (those unspoken questions: “Why are you looking at me? Why am I having to look at you?”).

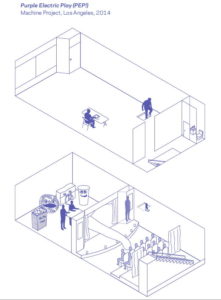

This attention to the frame is a constant feature of Hartman’s work, which includes nine productions to date. Early plays push the boundaries of various performance genres, as in The All Stars of Non Violet Communication (2011), which probes the conventions of stand-up comedy, exposing their violence, and Annie Okay (2010), which explores the “colonialist subtext in two of America’s most beloved musicals, Annie Get Your Gun and The King and I.” Later works, such as Purple Electric Play (PEP!) (2014) and Mr. Akita (2015), take on the histories and practices of theatre and painting. But while making us conscious of the traditions they’re working in, the challenge these plays pose is existential rather than cerebral: The frame—whatever it may be—simply cannot contain all the questions, life experience, and language Hartman and his actors jam into it. It fills to overflowing and explodes.

In this, to cite theatrical precedents, the Gawdafful National Theater is less like the coolly deconstructionist Wooster Group (though it shares their absurdist sensibility and dry wit), and more like the messily sincere Living Theatre. Indeed, when I saw my first GANT play I felt I finally understood, in a visceral way, what it must have been like to experience avant-garde theatre in the ’60s—to not just be made aware by a performance, but to be changed by it. As Julian Beck, who cofounded the Living Theatre with Judith Malina in 1947, wrote in his journal in 1959: “I dream of a theatre company, of a company of actors that would stop imitating … that would move the audience in such a way and imbue that audience with such ideas and feeling that transformation and genuine transcendence can be achieved.”

Like Antonin Artaud, his inspiration, Beck understood that the conventions of the theatre could not—or could no longer—achieve this, especially the conventional language of the theatre. Throughout the ’50s, the Living Theatre devoted itself to “poetic dramas” or “verse theatre,” seeking to be as experimental with language as it was with staging and performance. But by the early sixties they had suspended this project. “There has been some theatre verse in the last 20 years that I respect,” said Beck, “but not enough, and still too dependent on the verse spirit of other eras to speak directly, engagingly, to the audiences of our time. We wait and work, because when it happens it will happen because we are prepared for it. By ‘we’ I mean everyone, not only needing it, but wanting it, craving it.”

The work Beck and Malina did while waiting for this new language to emerge moved away from scripted texts toward improvisation, ritual, and the preverbal or nonverbal elements of theatre. As a director, Malina began “to let the actors design their movements, creating a remarkable rehearsal atmosphere in which the company became more and more free to bring in its own ideas.” Through the participatory “body piles” of Paradise Now (1968) and other rituals, they worked to free the body from its state of “thinghood”—whether in performing or watching—by producing conditions “in which the public can experience its own physical self, examine its being, its own physical being, its own holy body individually and collectively.”

In the late ’60s and ’70s, the Living Theatre’s legendary experiments went even further, into communal living, anarcho-pacifism, and revolutionary politics, as they struggled to create new forms of art that would open out onto new forms of living. But by their own admission, they never quite arrived at the “verse spirit” that could do that same thing. For this, we had to wait for Asher Hartman and his Gawdafful National Theater.

GANT’s ambitions are on a par with the Living Theatre’s: to resist the contemporary impulse toward “ultra-softness” in the theatre, by which Hartman means the avoidance of feeling. This widespread fear of stirring up the audience he views as a “denial of class and privilege,” insisting that we push beyond this “surface theatre” to the hidden truths we don’t want to acknowledge, “the thing that’s the thing beneath the thing.” This is just as true for his performers: Hartman sees his role in the company as “stretching people to go to places they don’t want to go, that I know they’re profoundly capable of going, and having them show up there effortlessly.”

How is this accomplished? What is the Gawdafful process? To begin with, you should know a few things about Hartman: He is a painter, with a graduate degree from CalArts and an undergraduate degree in theatre from UCLA. He has years of teaching experience in both painting and performance. Given his background, his networks and productions are, not surprisingly, transdisciplinary, and his actors hail from the worlds of theatre, music, and visual art. Hartman is also an intuitive with a well-established energy reading practice, and his plays and his process actively mine various energistic or affective registers in pursuit of new forms and the redeployment of old ones.

Each play takes six months to a year to develop in rehearsal, with the actors rehearsing three or four times a week, three hours at a time, in Hartman’s studio. The plays are written through a back-and-forth between Hartman and company members, with each play “built” on a particular actor or pair of actors. The building process begins with Hartman interviewing them, asking what they want to do, who they want to play, as he derives—or receives—mental images from their answers. He then goes off and “listens” for the characters who emerge, sometimes returning with as many as 600 pages of “automatic” (for lack of a better word) writing for the company to sift through to find what sits well on the actors. “He takes it all in from us—he’s photographing us, in a way, he’s doing spiritual photographs,” actor Philip Littell (he/him) explains. “And then he sends the bucket down this deep well. You can hardly hear it strike the water, it’s so deep, and up come his texts. They’re obscure and dense, but you know the stuff is in there, so you frack it, you apply more process to it—you put it together, take it apart, put it together, take it apart.”

These nuggets form the basis of the script, which Hartman continues to revise over the course of the rehearsal process as the company strives to break the habits of contemporary theatre via energetic work and exercises, deep meditation, “ancestral mining,” and structured improvisations of all sorts. Actor Chelsea Rector (she/her) describes how empathetic connections are activated among company members, drawing them into one another’s energy so as “to get at the unexpected outcome, usually filtered through comedy, violence, or sex.” It’s a process that “wakes you up, gets you working in your body, gets you in touch with the unseen.” As with the Living Theatre, Rector stresses how central the body is to the Gawdafful process overall, noting that everyone in the company has an “articulated movement vocabulary of their own, so we have an understanding of one another at a really physical level.” This work starts with the body, she insists—“the body in politics, rage, loss, and confusion.”

If the work starts with the body and its energies, it ends with poetry. Rector sees Hartman’s words as taking on a weight and solidity that’s unusual: “I’m talking like I’m moving because the language has such a topography to it.” While she concedes that it’s demanding on the audience, listening to the work pays off: “You can get a universe of information out of the pieces—and if you ask me, that’s the work of poetry.” Rector jokes that when she’s working on a Gawdafful play, her family often asks her, “Will the next one be about anything?” Her reaction: “I feel like saying, how do you not understand we’re creating your whole world in front of you?” For Littell, Hartman’s writing “has the flow of Shakespeare, the density of Stein, and the atmosphere of Beckett.” He notes its playfulness on the level of the sentence—“the language is so delicious— [Hartman] will take a phrase or a cliché and scramble it or stick it upside down”—but also emphasizes that it’s “deeply felt.”

The three plays collected in this volume—Purple Electric Play (PEP!), Mr. Akita, and Sorry, Atlantis: Eden’s Achin’ Organ Seeks Revenge (2017)—are the first by Hartman to be published. Can we say what they’re about? Perhaps it’s better, more fitting, to say what they contain—barely! Somehow, PEP! manages to hold Maurice Chevalier, the German Occupation, the French Revolution, vaudeville, TV variety shows of the ’60s and early ’70s, black-light theatre, and Britain’s Got Talent, to name just a few of its elements, many of which come together in the play’s early lines:

Friends of the Guillotine, Watch as, I, Actor,

Step on the stage. The epitome of style,

A Man who organizes sleep. You wan’ be me, Citizen, no? A Fagin with green lips

How to confess the diabolical things I’ve done.

Note the exits front and back, friends, Now is a good time,

No harm will come to you … If you’re thinking about it …

If we choose to stay for the performance, we are encouraged, in Hartman’s director’s notes, to “let the play take [us] through its many layers.” As with an energy reading, “meaning is established gradually, cumulatively, and without effort.”

Mr. Akita is a one-person show featuring a performer, Cliff Hengst, dialoguing with an abstract painting, Emily Joyce’s Sun Burn (Split) 1. Despite being Hartman’s shortest play to date, it nonetheless manages to incorporate Borscht Belt comedy, torch singing, meditations on abstract painting, the figure of the artist, and the teaching of art, as well as the mysterious dog Mr. Akita, who is at once professor, student, sexual predator, and lover. Sorry, Atlantis, Hartman’s most recent play, takes on “the spiritual roots of white supremacy, misogyny, and fascism as it plays out in contemporary American society.” As Hartman’s notes go on to explain, it “combine[s] the aesthetics of pre-war and WWII cartooning, archetypes of Greek mythology, the psychosexual underbelly of Jungian psychoanalysis, and gay and Shakespearean camp.”

In these plays, the visual writing is as layered and arresting and slyly irreverent as the text. Sorry, Atlantis’s floor-to-ceiling ramped stage, for instance, with well-positioned holes in the floor from which the various performers pop up, creates a suffocating feeling of no exit; the actors risk bumping their heads against a brutal ceiling when they try to stand and walk around. The dancing consumer-product puppets of PEP! (disposable diapers, a pizza box, Kleenex, a Big Gulp) come to life in a magical display of commodity capitalism; at play’s end, Mother Theater’s giant pneumatic purple tongue lunges from the stage to lick the audience. In Mr. Akita, the op-art sun of Joyce’s painting is a recurring image, all the way through to the play’s closing lines:

The Painting’s wound spreads, sun-like. Teacher says:

What is a sun?

Can anyone tell me? Can anyone tell me? Yes? Akita?

“A sun is the object that rages back.”

“Well, that’s not quite right,” teacher says. “But you’re very close.”

Then there’s the issue of setting to consider: For several years, GANT was in residency at the legendary Los Angeles alternative space Machine Project, where founder Mark Allen encouraged Hartman to transform the building to fit the needs of each production, making them in some sense site-specific. The Machine Project space closed in 2018, but Littell isn’t worried about having the work taken up in other contexts, by other actors. “The excitement of ‘having book,’” he says, “is that people will get the wrong idea, but imaginatively—the way we all got the wrong idea about Jerzy Grotowski from those grainy photographs. They excited us.”

There’s much to be excited about in this book, which opens up new horizons for the theatre and its language, and also for ways of coming together as we face an increasingly turbulent future. Philosopher and psychoanalyst Cornelius Castoriadis understood art’s mission to be “the exploration of ever new strata of the psyche and the social, of the visible and the audible” in order to give form to chaos, which feels like a good description of the work of the Gawdafful National Theater. In our chaotic times, too often rendered in dangerously simplistic terms, the company’s vital and complex excavations, captured here in the “verse spirit” of Asher Hartman, are a radical and necessary intervention.

Janet Sarbanes (she/her) is the author of two short fiction collections, Army of One (2008) and The Protester Has Been Released (2017), and numerous writings on art and politics, including the forthcoming essay collection Letters on the Autonomy Project.