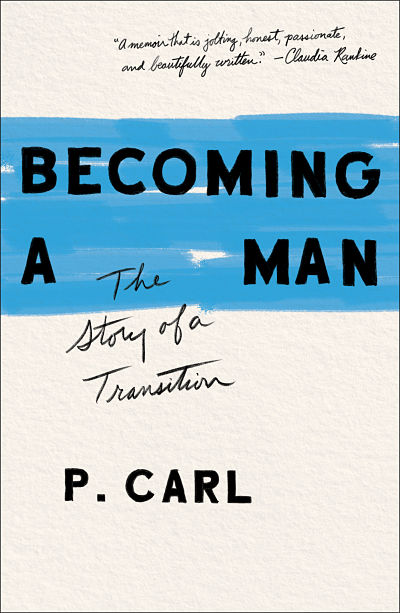

The following is an excerpt from Carl’s book Becoming a Man: The Story of a Transition (Simon and Schuster), which reckons with his midlife transition into his full self, in the body he always craved, at a bittersweet time. Carl, a longtime theatre dramaturg and artistic leader, has found himself in the awkward position of becoming a white man in Donald Trump’s America, a place where white male privilege is in full ugly backlash mode. In this eerily resonant excerpt, given our current moment, Carl uses 2018’s Brett Kavanaugh hearings, and the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford, as a prompt to consider what his body retains about having lived as a woman and what that teaches him as a man.

Chapter Nine: Polly

ELKHART, MINNEAPOLIS, TOKYO, CHICAGO, BOSTON

Devastation. That’s what makes people migrate, build things.

—Tony Kushner, Angels in America

My body knows intimately the life of a girl and a woman.

I am struggling with how to tell you about the things that happened to me because of my gender. I watched Anita Hill testify and now Christine Blasey Ford. Is there some kind of perfect tone a woman must use? I cannot ever forget Brett Kavanaugh crying out his victimization, yelling of conspiracies, trying to turn the tables as abusers do, his red, twisted, enraged face captured in dozens of photos, a face etched in the psyche of every woman who knows what’s true. When I try to write the stories of being a woman, I sound defensive. If we once thought depression lived in the spleen, where is my defensiveness located and could I use a linguistic scalpel to remove it? I write this chapter several times until the stories become disemboweled. My greatest anxiety in my transition is to lose track of what happened to Polly, to do to a woman what was done to me. In some ways, I know this has already happened, because Polly could spew toxic masculinity, and Carl tries to prove his maleness sometimes with a less-than-enlightened bravado. Mostly, though, I lived the life of a woman at the mercy of patriarchy and misogyny. I cannot forget. I can’t run from Polly—what kind of man would I be then?

My first day of graduate school in the fall of 1991, I am 25 years old and I am in the administrative offices of my new department. I am introduced to another first-year graduate student. He suggests we go for coffee. He tells me about his life in Nigeria and lets me know right away that his uncle is Chinua Achebe. I have read Things Fall Apart, an early exposure for me to the idea of precolonialism, and I love talking about books; the conversation is free-flowing and engaging. As my coffee grows cold because I don’t even drink coffee yet, and as the banter winds down, I ask if he’s taken the bus. I’m fretting over public transportation, having never used it before. He invites me to his place for tea so he can show me how to navigate the city.

We take a bus to his apartment. We walk up two flights of stairs. He puts on the tea and walks over to the apartment door, locking it from the inside as he pockets the key. My strongest memory is of the ominous feeling that shook my body watching the key slide into his pocket. The things a woman never forgets, like laughter, or the black leather belt he was wearing that day. He takes off his shirt and begins to take off his pants. I tell him I have to go. “No, no, no,” he tells me. “We will get to know each other.” I begin to shout, “Unlock the door, let me out!” over and over. I am pulling at the door frantically as he walks toward me. I am no match for his thick, six-foot frame. A few seconds feel like an hour. I know I am about to be raped. He unlocks the door, I run down the stairs and the three miles home. The phone is ringing when I get to my apartment. How did he get my number? “I think you are beautiful, please come back.” I hang up. The calls go on for weeks. I am afraid to go to campus. I never tell anyone. I know, because every woman knows, that if I show up on the first day of school and accuse a man of, of what? What do I call what he did? I wasn’t physically harmed. I know reporting what happened will jeopardize my entire graduate career, and classes haven’t even started yet.

Several months later I learn that he is harassing undergraduates; one in particular is afraid for her life. I tell my department chair, “I am coming forward now because I want to confirm that what these women are saying is true.” He wonders why I didn’t report this when it happened. I know why the next day when I walk into the shared graduate student office. None of the women of color and few of the men in my department are speaking to me. I am the white woman who accused a Black man of sexual misconduct; the politics are problematic. The men who run things will matriculate Achebe’s nephew in a matter of months. Though when I start to do the research, I find that he’s not Achebe’s nephew, but rather the nephew of Christopher Okigbo, a famous Nigerian poet but not one that I would have known at the time. He did collaborate with Achebe after this incident, so I can imagine he knew him, and he also knew the name to drop to get my attention. I learned from another graduate student who learned from one of the faculty that he had come from the University of Iowa with a reputation for harassing women and Iowa wanted him out. In a sleight of hand very familiar to me that I don’t know the details of, he was quickly handed his Ph.D. from the men running my department and then he disappeared. Problem solved. Nineteen years later, my thesis advisor emails me a news story out of Reading, Penn. After many years teaching undergraduates at Kutztown University, he met up with his wife at his sister’s home, sat across the table from her, shot her several times in the head and chest, then shot himself in the head. He was 64 and she was 37. I imagine the trail of women with #MeToo stories attached to him. I feel partly responsible for the death of his wife.

I went to college with a sweet, gentle woman who lived down the hall from me in our all-girls dorm. A Midwesterner from Ohio with a welcoming smile and kind eyes. My roommates once rearranged our dorm room while I was at the library and decided I didn’t need a desk. Sue and her roommates were my respite. I stayed with her in France once when we were in college, and she became a beloved high school teacher who taught French and took her students abroad to experience the culture as she had. After filing for divorce and a restraining order, her husband murdered her with a shotgun in his car in front of their home, the three children watching from the window, then he killed himself. Sue’s son says they were watching with the hopes that their parents were going to reconcile. He ushered the two daughters away from the window and called his grandparents, Sue’s parents.

Like any woman alive, I can keep going. The stories of threats and violence and terror are part of every woman’s life and the lives of her circle of friends. The stories aren’t always connected to horror; more often they are about the ways men undermine a woman’s knowing and the aspirations that come with it.

I am in Tokyo early in my tenure as the artistic director at the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis when I receive a call from my communications director to tell me “we have an emergency.” The press needs to speak with me right away. “Can’t it wait?” I ask. “I’m in the middle of a rehearsal here.” “It can’t wait,” he tells me. A playwright and former board chair of the Playwrights’ Center has written a letter about me and sent it to the press and the charitable foundations that give us money. My mind is racing to try to think about what I could have done. Did I clumsily fend off a sexual overture and inadvertently piss someone off? Is there a staff member who reached a limit working weekends and I missed it? Did I give offending feedback on somebody’s play? He tells me via a bad phone connection, “The letter complains you’ve focused too much on taking the organization national and left local playwrights behind.” I feel a huge wash of relief come over me. There is some truth to this, at least the part that I have focused on growth and increased fundraising opportunities. “This can wait,” I say. But a woman with ambition needs immediate intervention.

I’ve come back early from Tokyo and am at a conference room table in the basement of an 1880s church that houses this sacred space for playwrights in the Seward neighborhood of Minneapolis. I am interrogated by reporters and foundation officers about the letter, a scandal. I am sitting on my outrage hoping this will pass, but news stories are published and extra board meetings are scheduled and six months later a foundation president tells me she may not renew a grant, that she’s still sifting through what happened. I hang up the phone and throw my keys across the office. I storm out of the building, get in my green Honda Civic, and start driving. I don’t know where I’m going. I pull over to the side of the road next to a lush green park a mile or so away from my office where kids are playing soccer, and I call Lynette, choking and gasping in tears. She is at work and calls a friend who comes like AAA roadside service to rescue me. I end up in the psych ward, suicidal. I have never had an outburst at the office before, the keys thrown against my own office wall, not thrown at anyone. The harm I plan is toward myself. I must be crazy. My brain can’t make logic out of a situation, my detached body goes unhinged. A man’s conviction never has to be logical or legal or true when it becomes destructive and unstoppable and makes a woman doubt her sanity.

My sister-in-law says something that at the time I take with great offense. “It’s like Polly gets in a skirmish with some men at work and then lands in the psych ward. I don’t think she’s bipolar, just too sensitive.” In hindsight, she wasn’t far from the truth. When I look back at all those hospitalizations in my 30s, they came as I tried to assert my power, my intelligence, my leadership ability as a queer white woman. After each slap down, I thought I must be insane, a rage and frustration turned inward, a sense that I was a constant fuck-up, not worthy of living. My father had taught me early on what my big mouth would cost me, and every man who came after me in those years of trying to make my mark on my profession replayed those childhood traumas in my body, causing a physical and mental collapse that I believed was, as the doctors told me, the flip side of mania, the depression that comes after the grandiosity of thinking your ambition matters. But who was really crazy? If we learned nothing else from watching the Kavanaugh hearings, we learned that women asserting their truth and their power and their Ph.D.s make some men crazy and red-faced—men who will go to any lengths to put down, threaten, and erase the threat of a woman’s reality that impinges on their ambition.

And let’s pause for a minute. If you’re a man, like me but not me, you might wonder what parts of the stories I am telling are forgetting, as Blasey Ford was accused of, what really happened? It has to be more complex than “I was just doing a good job and that made some men angry.” How many times have I read about sexual harassment and wondered what parts of the story I didn’t know, or doubted that a woman was telling the truth? What is she leaving out? I distinctly remember siding with Bill Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky scandal because she said she wasn’t a victim. I didn’t want to believe women were so vulnerable, so disempowered. At the time, I also didn’t imagine the trail of women Clinton might have abused. As a woman, I would have rather been bipolar, something I could take medication for, than been treated like a woman—something I could not control.

A colleague and I attend a meeting together to develop a project with a local queer youth group. He says to me after the meeting, “This is going to be perfect for you. You’ll have a lot of fun with this one.” I begin working on a new play with the group and attend rehearsals in the evening twice a week as planned. I send an email update about the project and my colleague replies, “We need to discuss this. I am concerned that you are too focused on queer issues.” When we talk, he is adamant that I am off mission with my own “personal projects.” My brain cannot make logic out of this either. The collaboration and my participation in the project had been his idea.

I am in the sixth grade. My father is never home and he watches TV or sleeps when he is. He is not warm or affectionate. We are in the basement, our television room. There is no carpeting, just a cold cement floor with a worn rug thrown over it and a rattan set of two chairs and a couch that my mother found at a yard sale. The television is in a big, boxy brown cabinet, luxurious for the early 1970s; the TV is our most prized possession, and the Cubs are playing baseball on the WGN Channel 9 broadcast out of Chicago, one of three stations we watch. He is home in the afternoon. Is it a weekend? I am not sure, but I remember the sun coming through the basement well window, creating a glare on the television. I am surprised to see him. “Do you want a massage?” he asks me. “Huh?” He might as well be asking if I would like him to buy me a BMW to put into the garage until I turn 16. “Okay, sure, I guess.” “Get on all fours,” he says. “You’re becoming a woman. Your breasts are beginning to show. I like watching you change.” While I am on my hands and knees, he pulls my T-shirt over my head, and leaves it covering my face, a strange smothering, my small breasts dangling, while he gets down on the rug and crawls over the top of my back and begins rocking himself on top of me. It’s a quick “massage,” and I feel uncomfortable and confused. I stand up and put my shirt back on and I never think of that moment again, until I ask a therapist about it at age 30. Whatever that moment was, it never left my body, proof that I was a daughter once.

There was the white male porn addict who everyone in the office knew about, who more than one woman had walked in on while he was glued to his computer screen. My white male friend complained to me daily about him, but did nothing. I went to human resources and filed a written complaint on behalf of the women who reported this to me, bound by the rules of the institution to do so. An invincible white man, the porn addict’s best friend, took me to dinner four months after I filed the complaint. “I know what you did and I wanted to fire you, but human resources wouldn’t let me!” The vice president of human resources showed him the letter without telling me. He was stunned by my betrayal, and the chill that had grown between us now made sense. I learned I wasn’t the first person to turn in his friend, and this wasn’t the first institution that had protected them both.

In the process of transitioning, of becoming the very thing that had made my life and my career a series of threats and clashes and near firings, I started hearing everything at high volume, like the repetitive droning while being trapped in an MRI scanner—all the language used to talk about women piercing my tender new male body. Men talk about women in ways that I must have been numb to before my transition. In a heated conversation about creating programs to make the theatre more gender-inclusive, a white male colleague gets frustrated with me. “I don’t get your concern for women and gender as a social justice issue; plenty of women attend the theatre.” I wasn’t talking about the older white women who buy tickets, but the women artists and queer artists and queer audiences who have been made nearly invisible in the stories we see onstage. He implied later in the conversation that my gender and queer preoccupations were racist.

One day, fully grounded in my male body, I listened to two men talk about a female CEO. “What’s with her hair, and those clothes? She has no gravitas. It’s hard to look at her when I’m talking to her.” Another man at lunch with me referred to a woman who had failed to respond to an email as a heifer. I start to feel the misogyny of everyday conversation on behalf of Polly and what she endured. I also began to think about my own complicity in conversations like this, the ways in which women join these conversations with men at the expense of other women. My body feels the shame of it for the first time.

Meanwhile I am being heartily welcomed at restaurants and hotels and by the parking valet and the guy at the men’s clothing store and the Lyft driver and… I suddenly feel all that I had been denied, all that women are still being denied. I don’t have enough imagination to know what women of color feel. Becoming a white man showed me how as a woman fighting for equality I had only been rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. The injustices I had experienced as a queer white woman come at me with the same intensity that I can now feel Lynette’s love and anger, or the newly coveted beard on my face.

You cry, but you endanger nothing in yourself. It’s like the idea of crying when you do it. Or the idea of love.

—Prior to Louis in Angels in America

I turn to Tony Kushner’s Angels in America—a text I have taught numerous times. Kushner is a prophet in the ways he exposes human vulnerability and the fragility of white masculinity. I am looking for a way through. How do white men in positions of power endanger something in ourselves? Can we learn from that brilliant moment in the play when Louis is talking to Belize about race and says, “What? I mean, I really don’t want to, like, speak from some position of privilege and—” The sentence ends there. Kushner knows not to finish it, because that is where Louis speaks from in this exchange. He thinks his theories of race are equivalent to what Belize knows through his lived experience. I have heard so many white men use that same opening qualifier. One way not to speak from privilege is not to speak at all. There are others ways too, but this can be a good place to start, to simply not finish your sentence.

I am having a trauma response right now. I can’t catch my breath. I wrote “not to speak” and then I felt Senator Lindsey Graham in my body. What is the purpose of this chapter when a man like that can mow down women as a way to never endanger the lobbying money he will get when he leaves the Senate? After the riveting and truthful testimony of Christine Blasey Ford against Brett Kavanaugh, he rages at the injustice done to a white man, “This is going to destroy the ability of good people to come forward because of this crap.” He wants to personally ensure we never come forward again. He and his ilk will never stop speaking.

You can’t live in the world without an idea of the world, but it’s living that makes the ideas. You can’t wait for a theory, but you have to have a theory.

—Louis, Angels in America

I don’t believe anymore that it’s a new theory of inclusion or economic policy that will save us. We have enough data to know that it’s bodies that are tripping us up. All the men referenced in this chapter who are still alive know the theories, hold well-considered, if in some cases despicable, political positions. They would all identify themselves as “good men.” In Angels in America, Prior says, “Louis, he can’t handle bodies.” Louis doesn’t want to be around the lesions, the secretions, the suffering that comes with AIDS. Men of every political viewpoint cannot handle bodies, the ones across from them nor their own. Women’s bodies elicit a rage that no theory seems to be able to undo. Men sit around a table and they are brutal with one another. They yell, they pound fists, they make cutting jokes about one another, and often they hash things out with a modicum of success. When they leave the conference table, they shake hands and grab a drink together. They can handle one another’s bodies. A woman who pounds her fists never gets a second chance. Her body is limited by the gestures it can make and the words she can say and the volume at which she can say them.

My body has never conformed; it’s from this vantage point that I understand how privilege can’t be fully known when sitting inside it.

God splits the skin with a jagged thumbnail………… He pulls and pulls till all your innards are yanked out. . . .Then he stuffs them back dirty, tangled, and torn. It’s up to you to do the stitching.

—Mormon mother in the diorama, Angels in America

I wish I had written these lines to describe what a gender transition feels like, at least one at age 50. Transitioning and trying to leave womanhood behind split open my skin in an entirely different way than living as a woman did. When trying to escape Polly, she refused to be let go of like the strong woman she was. I’m finding the entirety of my entrails of my insides and trying to stuff them back in this body. Perhaps we must all yank out our own innards and stitch ourselves back together, to transition together and acknowledge all the ways that we are forced to double.

Kushner wrote Angels in America to give us hope, to believe as we all want to, all of us who fight for social justice, that “the world only spins forward.” This is Kushner’s most important theory in the play, and it’s what keeps us all fighting for cures for AIDS, and the right to marry whom we choose, and the right to live in the gender that is ours. I keep thinking of the grief and anger I felt watching the play 25 years ago as a newly out queer woman volunteering in a hospice facility for men dying of AIDS; and the grief and anger I feel now, 25 years later, watching the revival of the play on Broadway as a white man realizing the world didn’t spin like I thought it would. I write as Kushner did in his introduction to the play, “on the edge of terror and hope” for the women in this country.

P. Carl (he/him) is a distinguished artist in residence at Emerson College in Boston. He is also a writer and lecturer on theatre, gender, inclusive practices, and innovative models for building community and organizations. His theatre background includes leadership positions at Playwrights’ Center, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, and HowlRound.