Any good improv performance proves the value of adapting on the fly, whether it’s to a fellow performer or an audience suggestion. Thinking quickly and staying nimble is crucial even outside of a performance, especially when faced with the many issues continuing to face the theatre field as a whole as a result of an ongoing pandemic and unceasing closures. Whether it’s reshaping content to fit a new medium, staring down the possibility of permanent closures, or facing their own reckoning with a legacy of racial and cultural exclusion, improv and comedy theatres are learning just how important it is to be able to listen and adjust.

In March, for instance, the Atlanta improv theatre Dad’s Garage took a different path from many theatres who pivoted content to meeting tools like Zoom, venturing instead into Twitch. Since Twitch is a platform mainly aimed at live-streaming gaming, Dad’s Garage artistic director Jon Carr saw an opportunity to stand out.

“We wanted to be a big fish in a small pond,” Carr said, “so that we could be a company that could eventually get to the front page of Twitch. On something like YouTube or Facebook, we would kind of just fade into the background and would only be playing to our original audience. Whereas on Twitch, we have an opportunity to find new people that maybe would have never heard of us otherwise.”

Dad’s Garage’s Twitch audience has grown to over 2,100 followers, and the company is aiming to become part of Twitch’s Partner program, an exclusive group of top creators on the platform who must be approved by Twitch, who Twitch says “can act as role models to the community.” Carr added that among the attractions of Twitch were some its built-in revenue opportunities, including allowing their audience to donate directly to the company through the site and subscribe to them through monthly subscriptions of $5, $10, or $25. A move into the partnership program, Carr hoped, would add buying merchandise to that list.

Benefits of the platform aside, finding the right content to live-stream there put the company to the test. But, like good improvisers, they approached the opportunity as a way to try many things and let the audience dictate what programming would eventually stick. The first few months, Carr said, they were broadcasting around five hours of content, six days a week, with performers taking half-hour to hour-long blocks to experiment. Included in this trial period were replays of old improv shows, but Dad’s Garage soon realized that these did not capture the form’s the organic spontaneity.

“We very quickly realized that just converting things one to one wasn’t working, in the sense of taking an improv show that we do on our stage and then trying to do it in a Zoom atmosphere or on Twitch,” Carr said. “It just doesn’t translate. So the biggest learning curve has been: What are the skills and abilities that we have that came from improv that can translate and help us build Twitch stuff? There has to be something that makes it unique and specifically and wholly designed for Twitch.”

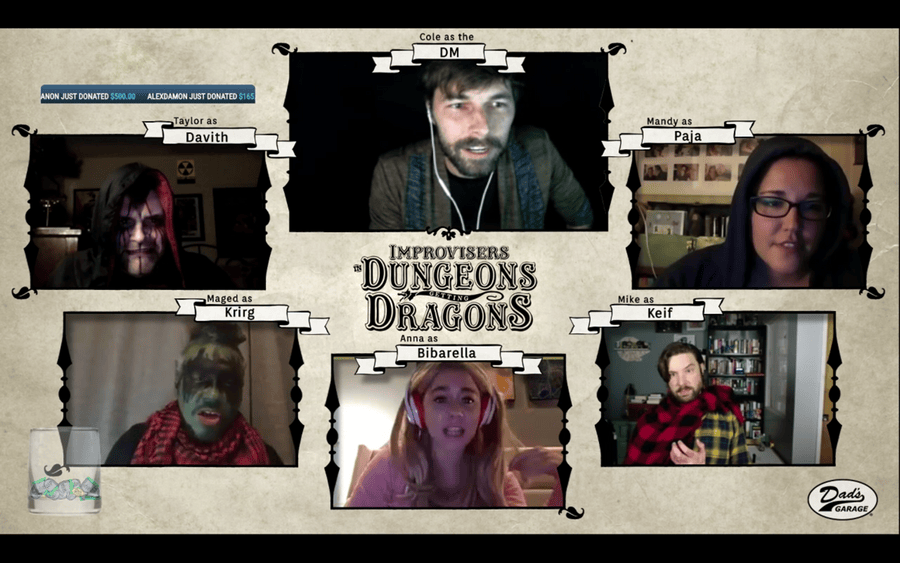

In this playground of experimentation, Dad’s Garage performers have begun to play around with different formats somewhere between the company’s stage work and the sketch videos and short films it makes for Dad’s Garage TV. Some ideas that have sprung up over the months: adapting their improvised soap opera Scandal! to be about super-villains forced to quarantine and discuss their evil plans over Zoom meetings; streaming for 25 hours straight to celebrate the company’s 25th anniversary; and playing Dungeons and Dragons, an existing interest of Dad’s Garage improvisers.

Though Dad’s Garage has found a niche on Twitch, Carr emphasizes the importance of finding the right platform to fit the content. As with many improvisational ventures, it’s key to give yourself room to learn, fail, and give trial and error time to see what sticks.

“At the beginning of this,” Carr conceded, “it was very hard and very uncomfortable and we hated it a lot. But now that we’ve been through this, we’re starting to see some of the long-term benefits. We’re doing improv classes online and it’s been great. When you see someone from another state who’s jumped into one of your improv classes that under any other circumstances would never be able to do that—it has definitely, in a weird way, kind of made the improv world smaller and more connected than I think it ever has been. I think that’s the thing that I want to take with me: the connection with the people that I’ve met, the conversations, the people that I’ve been able to collaborate with that I would have never been able to collaborate with in any other circumstances. Those are the things I hope continue for the next decade.”

“You get stuck in a box sometimes where you’re like, ‘This only works one way,’ because you’ve done it so long.”

In Los Angeles, the Groundlings’ transition online started out much like Dad’s Garage’s: experimenting to find a way to put on some semblance of a show. Groundlings Main Company member Leonard Robinson explained that shows like their popular long-form improv show The Crazy Uncle Joe Show have seen around 60 to 70 people joining the performance-via-Zoom webinar. While that number is not insignificant when put into relation to the company’s physical theatre’s capacity, which seats around 100, Robinson admits that there’s no duplicating the live experience.

“You can’t deny that, when you’ve got a good bit going, you want to keep it going,” Robinson said of trying to feed off an audience virtually. “The weirdest adjustment is knowing that you can’t hear the audio, but knowing that they’re there. Often we judge the reaction by people who are in chat and are chatting afterwards. Sometimes the feedback happens after you’ve done a thing. Like if somebody said, ‘That was hilarious,’ you breathe a sigh of relief, like, ‘Okay, I’m glad you enjoyed that, because I had no idea.’”

Despite that disconnect, Robinson notes that these virtual performances online have opened the door to wider audiences, including viewers from places like London and Australia. That wider viewership and attention has even seen Groundlings, who Robinson said had previously not provided online classes, venture into the world of digital improv and comedy training.

“We’ve also found that some people watched the show, and then because they enjoyed the online experience, they feel like, ‘Well, let’s check out a class now,’” Robinson said. “There are plenty of people who would love Groundlings-style training and don’t have the desire to move to Los Angeles. It’s allowing us to reach those people and provide a service for them. I think, looking forward, we’re going to try and find ways to keep making offerings online and seeing how we can use that medium to our best advantage and enhance that product.”

Robinson recalled a student who had flown from Australia to take a class with the Groundlings who now wouldn’t have to do that. These changes, Robinson said, have opened the company to a customer base that they hadn’t realized was out there. He said he hopes that high school, college, and university programs across the country will now be able to check out the Groundlings and even potentially supplement their drama programs with Groundlings classes.

Chicago’s the Second City has found itself making similar discoveries, according to interim executive producer Anthony LeBlanc. The company, he explained, has found itself having to embrace many practices that they had been teaching others over the years: being able to listen and adapt in the moment, collaborate, and pivot and change on a regular basis. LeBlanc related these shifts to the realization that has happened in many industries around the country, where people have discovered that jobs that were previously thought to need to be done in an office can actually function well through telecommuting.

“The thing that was actually the most surprising thing is how well it translates to a certain degree,” LeBlanc said. “You get stuck in a box sometimes where you’re like, ‘This only works one way,’ because you’ve done it so long.”

While LeBlanc says there is a little extra work that goes into being able to connect to fellow performers through a virtual device, he also says that a virtual format has allowed performances to pull audience members into shows in a new way, including taking suggestions via audience members voting through chat polls. Much like the Groundlings, LeBlanc sees Second City reaching audiences who might otherwise not have come to the physical theatre, be that because of distance or access. Second City, in addition to its expected improv, writing, stand-up, and acting classes, has also transitioned its wellness programming online, which includes classes for people over the age of 55, people with anxiety, and people on the autism spectrum.

“The thing that we’re learning a lot from this is about access,” LeBlanc said, “and really focusing a lot on how this new thing you’ve been forced to do allows more people to enjoy and participate in things that happen. I think that we will always have some version of these virtual classes that we’re doing because we have learned that people from all over are able to participate in these things that normally wouldn’t be able to come down to the physical Second City all the time.”

Access, of course, isn’t just tied to physical space. Like all theatres across the country, the comedy and improv community has been facing its own reckoning. The pandemic has forced a few famed comedy shops to close their doors permanently: April saw Upright Citizens Brigade close its New York locations, and the owner Chicago’s iO Theater cited “looming property taxes bills” as the company announced in June that it would close permanently and sell its building. Even my hometown improv troupe, ComedySportz Indianapolis, announced that it would have to leave its home of 21 years.

Comedy stalwarts, including iO, Groundlings, and Second City have also faced allegations of racism and exclusion within their communities. Current and former performers of the Groundlings sent an open letter to the company demanding systemic change from “a theatre that touts itself as a meritocracy while operating like a country club.” A week before the Chicago Tribune reported on iO’s closing, they also reported on a Change.org petition calling for systemic changes throughout the organization to create “a genuinely inclusive space for QBIPOC and folks of all abilities.” And Anthony LeBlanc’s move from artistic director for the Second City to interim executive producer followed the resignation of Second City co-owner Andrew Alexander amid social media allegations of years of institutionalized racism within the company.

LeBlanc notes that one good byproduct of the pandemic has been the chance for businesses to truly examine how they exist and operate. That, combined with the swell of social activism, has pushed these companies to think about how, if it’s going to take rebuilding to bring the community back, they rebuild the right way next time. LeBlanc said his company is committed to finding the right way to create a space that is welcoming to everyone. He said that Second City wants to be an industry leader by being public and transparent with their adjustments, the better to share and model changes for other companies.

“I think it’s very much our responsibility as Second City to make sure that we are fostering, giving a home to, and helping to support the community at large,” LeBlanc said, mentioning that he’s hopeful that Second City will be able to provide a space to perform for people throughout the city once the company is physically able to open its doors again. “We’re doing all the things to make sure that this rebuild is done in the best possible way, that this is a place that’s welcoming to everyone. It’s also being very public and transparent with that and being willing to share that change and how we’re doing it with people. We’re 100 percent wanting to be the people who become leaders in that, and really accepting that opportunity in that moment.”

It’s easy to look at the closures, and at patterns of systemic racism and exclusion, and worry about what the next steps for improv and comedy theatre will be. After all, it’s what we’ve been doing with other forms of theatre for months: contemplating what theatre once was, what it will become, and what should be thrown out between the two. Perhaps, as improvisers have shown time and time again, the best—and most enjoyable—way forward is to begin to genuinely listen and adapt: to audiences, to fellow performers, to the passions and directions of the country as a whole. The ability to listen and actually say “yes, and…” might be the best, indeed only way to rebuild.

“When people talk through the idea of, ‘Things aren’t going to come back,’ you have to look at the idea of what ‘come back’ means,” said LeBlanc, whose hometown of Beaumont, Texas, just last week saw a mandatory evacuation notice in advance of Hurricane Laura. “Physical places might go away, and that’s always sad. Some businesses might not ever reopen. But going through so many rounds of hurricanes in my life and having a lot of my friends move up to Chicago post-Katrina—so many people went back. Enough people went back and rebuilt. A community is larger than just the buildings. And I think that’s very true about improv.”