We theatre practitioners often like to imagine the theatre as a liberal, progressive beacon of light in an otherwise racist and backward culture. But since the start of ongoing protests against police brutality that arose this summer in response to numerous murders of Black civilians, the inclusive image many of us may have of the American theatre is being challenged more and more by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) theatremakers, who are releasing statements and making demands for long-overdue change. In addition to callouts of the nation’s commercial and nonprofit theatres, another locus of this anti-racist activism is university theatre programs. Students and alumni of programs all over the U.S. have taken it upon themselves to boldly tell stories of their experiences.

These have included racist statements and judgments—one Black student in Syracuse University’s theatre program was told she “passed the ‘paper bag test,’” an infamous measure that upholds colorism by excluding those whose skin tone is darker than the color of a brown paper bag. Another heard a white professor say to two Black women, “You bitches aren’t even thick.” A Black acting alumni of Rutgers’ Mason Gross School of Acting reports another all too common microaggression: having her hair repeatedly pulled by a white teacher.

More broadly, Black students also note a tendency toward Eurocentric and white-authored programming and standards, a scarcity of teachers of color, and tokenization. In a letter addressed to Florida State University’s Asolo Conservatory, signed by many students and alumni, students recount a leader of the theatre parading five Black students out at an event, saying, “Look! There’s five of them,” as a self-congratulatory presentation of the program’s diversity.

These personal testimonies are just the tip of the iceberg of experiences related by students and alumni who have joined to call for an end to the racism they’ve faced in their theatre departments. Formatted in letters, public statements, and calls to action, these meticulously organized documents, some spanning more than 30 pages, detail the racist practices, both overt and implicit, they say are still prevalent in American theatre’s collegiate training programs. Theatre programs at Syracuse University, Rutgers University, Florida State University, Juilliard, and Stella Adler Studio of Acting (which partners with New York University), are just a few of those that have been the subject of these statements thus far.

Though these letters were written by and on behalf of all BIPOC students and alumni, in reading through many of the statements and testimonies, it’s hard not to notice a throughline of anti-Blackness and misogynoir. In fact, several of the preliminary statements made were organized, inspired, and/or led by Black people, often specifically Black women. In talking to several organizers of the statements, I found they were spurred by a mixture of dissatisfaction with the way their universities responded to the recent police killings of Black people, and the hypocrisy they saw when those institutions did step forward to condemn racism, even as it permeates their drama departments.

The strategy of holding their theatre programs openly accountable with large public statements was inspired by the recent surge of BIPOC folks stepping forward against racism and exclusion in the theatre field, most notably with the We See You White American Theater, a movement that began with a high-profile signed letter and more recently released a 30-page list of demands for the theatre community at large (there is a section on education and training). This medium for speaking directly to power to address systemic inequality is also a way to bear witness to the damage that racism can do.

School leaders “need to take our notes, because we spent a lot of money taking notes from them and came out, especially the BIPOC students, especially our Black students, with a lot of trauma.”

“I was talking to another girl from my class, and I told her a lot of the racist things that happened kind of defined our time at Rutgers,” says an anonymous Rutgers alumni, and one of the Black women whose experience was a catalyst for their statement. “Whereas, if the teachers were to think about it, they may not even remember problematic things that have happened or upsetting things they’ve said, or things that greatly affected my ability to learn in the classroom.”

These statements also give us the chance to watch in real time as students and alumni organizers inspire and build off of one another’s work. One illustration: the similarly themed hashtags that students from Syracuse and Rutgers are using in conjunction with the letter: #TaketheNoteSUDrama and #TaketheNotesMGSA. This use of the adage “take the note,” while currently only tied to these two statements, perfectly encapsulates the spirit of these letters.

“‘Take the note’ is specifically about the acting world, director/actor relationships, because most of the faculty at SU Drama are also our directors,” explains Syracuse alumni Courtney Green. “That’s who we were mostly speaking to, our directors/faculty—our acting instructors, who tell us to take the note and how to take a note appropriately. We were saying ‘take the note’ in the same way that they have taught us to.”

Those sentiments were echoed by Rutgers alumnus Katie Do, one of the organizers of a statement to her own alma mater about its racist practices. “When you take a note in acting class, you’re constantly asked, can you take notes well? Or you’re told you have to ‘take that note better.’” Now, she adds, leaders “need to take our notes, because we spent a lot of money taking notes from them and came out, especially the BIPOC students, especially our Black students, with a lot of trauma.”

Indeed, the average cost for an out-of-state student to attend a public four-year institution is currently $38,330 a year—a steep price to pay for racism, especially in a country currently giving it out so freely. Which is yet another reason these students’ notes on the inequality in their drama departments should be taken, and taken seriously.

The notes being given to these institutions are nothing if not thorough. Most of the statements written thus far have followed a similar format: an opening that names and condemns the pervasiveness of racism within the institution, personal accounts of racism experienced by students and alumni, and a straightforward list of actionable anti-racist steps the department should take. The statements typically end with a list of signatures from students and alumni who either contributed to or simply supported the content (Asolo Conservatory’s statement, for example, boasts playwright Lynn Nottage as a notable signator).

Though not completely uncharted territory (a student group made a statement and petition condemning racism at South Connecticut State University last year), the form and reach of these recent statements seem unique to this moment. Indeed there were a lot of similarities in the reasoning and process behind these letters and statements. In many cases, student and alumni organizers used surveys to solicit experiences and opinions from BIPOC and white students, including questions about any and all racism they’d experienced or witnessed during their time in the department. Some surveys, like Syracuse’s, also asked for ideas on what changes students and alumni felt were necessary. Several of the letters also included facts and statistics about diversity in their departments, from playwrights showcased to casting practices to diversity in staff and student body.

“We did a history project like no other,” explains Bonita Jackson, an MFA student at FSU/Asolo Conservatory and one of the leading organizers of their statement. “We dug down into the vaults. And not only did we look at over 21 years of the Asolo Repertory Theatre’s seasons, but also the FSU/Asolo Conservatory’s seasons.” Led by a group of five, the students reached out to Black alumni from as far back as 1996. They discovered that Black alumni account for just 6 percent of graduates between 1999 and 2020. Six percent.

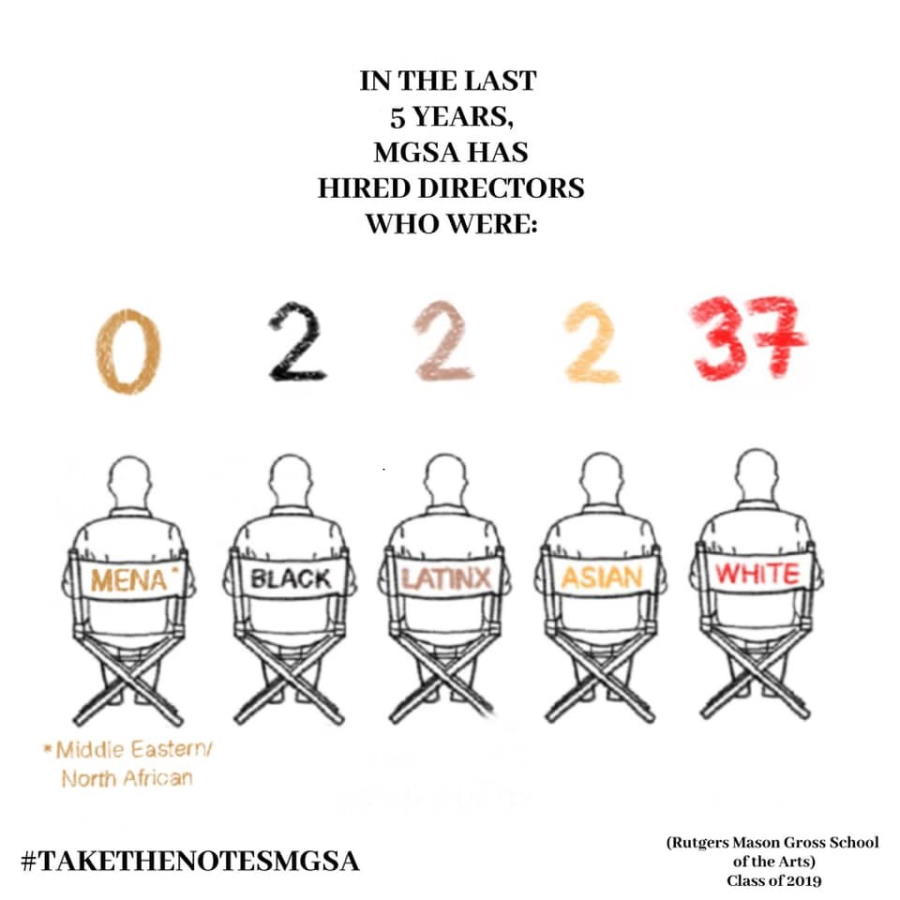

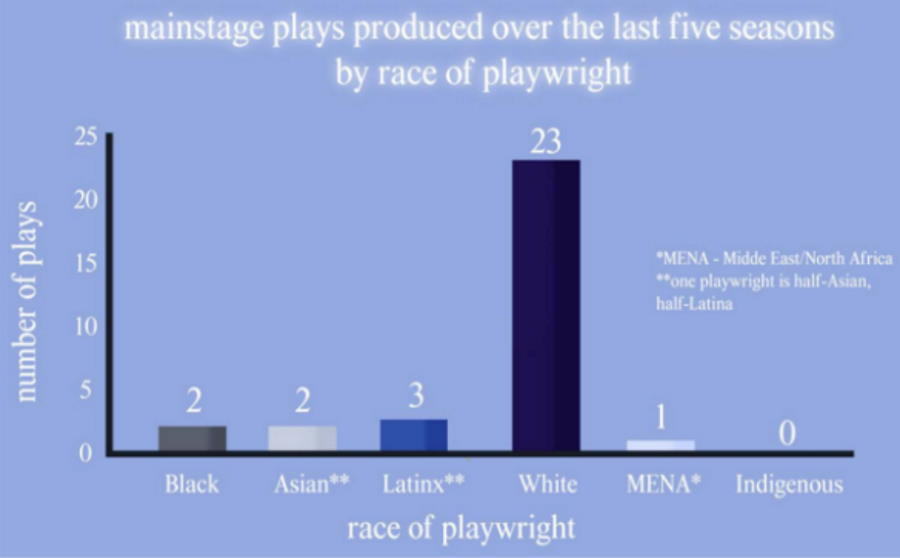

That paltry percentage isn’t the only staggering statistic from Asolo or other universities demonstrating their lack of diversity. Since its inception in 1958, the leadership of Asolo Repertory Theatre, for one, has been entirely white, including executive directors, managing directors, and artistic directors. (In this, Asolo is, unfortunately, hardly alone in the U.S.) A statement from students and alumni of Ithaca College Theatre Arts showed that only three current faculty members out of 35 are not white. The statement to Rutgers revealed that in the last five years, MGSA has produced plays by only three non-white playwrights—one Black, the other two Latinx/Hispanic—while the other 43 playwrights produced were white.

Led by a group of five, FSU/Asolo Conservatory students reached out to Black alumni from as far back as 1996. They discovered that Black alumni account for just 6 percent of graduates between 1999 and 2020.

These examples indicate a problem more deep-rooted than racist comments or attitudes. Accordingly, the actionable steps or demands from organizers aim to strike racism at its roots in university settings, including hiring more BIPOC staff, anti-racism training, curriculum and show changes to center more BIPOC voices/stories, and avenues for BIPOC students to safely speak out and be heard without fear of retribution. Many of the letters’ demands dovetail with those outlined in the We See You White American Theater document. However, there were also demands unique to each university’s program. The statement addressing Winthrop University’s CVPA Department of Theater and Dance, for instance, demanded that the department abolish the hair and nail requirements listed in dance syllabi on the grounds that they’re specifically discriminatory against Black female dancers. While the portion of the letter to Rutgers’ MGSA that contained the changes they are asking for was sent privately to faculty and wasn’t publicized, organizers shared with me that one big contributor to racist programming is a grant that conditions its support on a certain number of Eurocentric works being staged.

Many of the asks and recommendations in these letters were carefully tailored for maximum actionability. In the call to action to Syracuse, for instance, the organizing team worked with a professor who happens to be related to one of them to make sure the statement would be as effective as possible, and that the demands they listed could all be feasibly met by the drama department.

“One thing we wanted to make sure of when we sent out this letter was that it wasn’t just, you know, a baseless letter with no suggestions, with no ways to want to improve it,” Courtney Green explains. “We didn’t want it to come off like a callout or like a character assassination of just us trying to attack Syracuse. We wanted to hold them accountable and help bring them to the standard that they try to present themselves as and that we think that they’re not quite at yet.”

So what has the response been from the universities? In Syracuse’s case, drama department chair Ralph Zito, spurred by alumni on Facebook, issued a response. Zito has been in communication with the organizers, and they’re currently working together to discuss and meet the demands outlined in the call to action statement.

Some of the department faculty’s plans include participating in an anti-racism workshop series with the staff of Syracuse Stage. Also on the docket is a reexamination of the school’s performance opportunities for students. “I am going to be talking with my faculty and my production department about fundamentally reconsidering how we select, produce, and cast our department season,” says Zito. “The fact that we do it so far ahead boxes us into corners that makes it more difficult for us to be as responsive as we need to be to the needs of our students.”

Meanwhile, at Cornell University—the subject of Chisom Awachie’s Open Letter to Cornell’s Department of Performing and Media Arts—staffers on summer break have convened to address students’ concerns as swiftly as possible. Awachie’s article recounts her experience with racism during her time in Cornell’s drama department. The statement is a bit different than others made collectively in that it’s written as a personal testimony. Nevertheless, her powerful words resonated with others and garnered the attention of her alma mater.

Department chair Nick Salvato, along with faculty members, spent the past month carefully setting into motion the action items detailed in the department’s earlier response to the Black Lives Matter protests. Notably, the school hosted a closed discussion on July 23, done in Lois Weaver’s “long table” format, about the university’s casting practices and the process of selecting and developing projects for each school year.

Beyond the event, the department has already shifted its production selections for this coming year. In the fall, BIPOC students will have the opportunity to devise a piece with BIPOC faculty members that explores the Black Lives Matter movement. The previously scheduled 2021 spring production of a Chekhov play will be replaced by a work by a yet-to-be-announced BIPOC playwright.

Further efforts of the school include a recognized need for regular anti-racism and microaggression workshops for faculty, an overhaul of the curricula (including a revamping of its entire syllabus for its introduction to acting course), a change of the play selection process that will invite undergraduate and graduate students to submit plays, and the initiation of an anonymized system for reporting experiences of racism. It will take more than a summer of restructuring syllabi, and certainly more than a long table, to right the wrongs, something Salvato recognizes. But this appears to be a swift start.

“I am going to be talking with my faculty and my production department about fundamentally reconsidering how we select, produce, and cast our department season.”

Not all of the call to action statements have been met with that level of detail and specification. As of the time of writing this, organizers of FSU/Asolo Conservatory’s statement have met with the conservatory as well as the repertory in separate meetings facilitated by FSU administrators. Together, they worked through a draft of an anti-racist plan, of which includes FSU/Asolo Conservatory starting anti-racist trainings for faculty and staff before the start of the fall semester.

Still, the organizers found the plan presented to them wanting.

“We were disappointed to learn that the Asolo Repertory Theatre and FSU/Asolo Conservatory created a combined draft of an anti-racist action plan,” says Bonita Jackson. “As one of the largest regional theatres in the Southeastern United States, it is paramount that Asolo Rep have their own anti-racist action plan. At the meeting with the Rep, we inquired about their separate anti-racist plan, and urged them to create one. Linda DiGabriele, [managing director of the Asolo Rep], says that they are working with a third-party consultant to work on their theatre’s separate plan.”

Rutgers organizers said they did receive a general response from the department and, at the time of writing this article, are planning a Zoom call to talk with department leadership. However, there were no personal accountability statements given from current faculty within two weeks of organizers sending the document—an action they had explicitly asked for in their statement to MGSA.

Dean Jason Geary sent a statement out on July 20 to the Theater Department faculty and recent alumni. The email from the newly appointed dean, who rose to his position July 1, expressed his agreement that the university needs to do better and outlines specific actions Mason Gross will take. “I can also say as a Black man who has spent the last 28 years as a student, faculty member, and administrator in higher education arts programs spanning the country, that Mason Gross is not alone among its peers in needing to address longstanding issues of discrimination, bias, and institutionalized racism,” stated Geary in the letter.

Action items outlined by Geary, that the administration is currently working toward, include:

- Increasing the number of works by BIPOC artists that are performed, programmed, exhibited, commissioned, taught, or otherwise highlighted within Mason Gross

- Increasing the number of BIPOC faculty at Mason Gross, with a focus especially on full-time, tenure-track faculty who are most responsible for shaping curriculum and who wield the most influence within the university hierarchy

- Increasing engagement with public schools and surrounding communities with the goal of facilitating access to the arts for communities of color and of creating pipelines to further diversify the Mason Gross student body

Other action items on the list including a commitment to helping establish mentoring networks for BIPOC students and alumni, creating opportunities for anti-racist training for the faculty, staff, and students, exploring ways curricula can be more inclusive, and publicly articulating on its website the anti-racist actions Mason Gross is taking.

Many schools, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, made statements dedicating themselves to anti-racism and allyship, and affirming their care for Black students. Some also mentioned their commitment to change and to finding ways to be more anti-racist in their teaching. But what we’re seeing from this moment is that many of the answers and ideas they’re seeking are already being given to them by their students and alumni. BIPOC students and alumni are a primary source like no other. These are people who have firsthand experience with these theatre programs and are the authorities on their own experiences as BIPOC students. Likewise, they have a genuine connection with these departments and a stake in wanting them to be better.

And while it shouldn’t be expected that these organizers “fix” racism at these universities, some students, as illustrated by these letters, genuinely want to help make their theatre departments better and safer for new generations of BIPOC students. A central aspect of the change being asked for, which these statements are quite literally spelling out for us all, is the right to be heard, seen, and believed. “There needs to be some acknowledgement and ownership of contributing to institutionalized racism and blatant racism that occurs in both of these institutions,” asserts Naire Poole, another MFA student at FSU/Asolo Conservatory and an organizer of their statement. “Until that ownership is taken, we can’t move forward. Both institutions and others like them must take accountability in order to take the actions to move forward to make true changes, lasting changes for artists, creators, the people who love the theatre, who love each other, who love this world and want it to be better.”

As more students and alumni are inspired to share the truth of their collegiate theatre experiences, theatre programs may want to remember a basic principle of acting and apply it to real life. Being given a note is not a form of criticism or hate; it is instead something a director feels needs to be done to make the production the best that it can be. Your students and alumni are giving you notes, university theatre programs. It’s up to you to decide if you’re going to be good performers, instructors, and allies by taking them.

Statements & Testimonies by Students and Alumni to University Theatre Programs

Cornell University: An Open Letter to Cornell’s Department of Performing and Media Arts article by Chisom Awachie

FSU/Asolo Conservatory for Acting Training: A Call to Action FSU/Asolo Conservatory, Florida State University, & Asolo Repertory Theatre from various students and alumni

Ithaca College Theatre Arts: letter to the school and department from students and alumni (they also have an Instagram)

Juilliard Drama: A Call to Action from Juilliard Student Congress

New York University: Racism at NYU Tisch Instagram page with testimonies from students and alumni

Rutgers University: A Call to Action from current students and alumni

Pace Performing Arts: video statement from See Our Truths (comprising students and alumni)

Stella Adler Conservatory: A Call to Action from the Students of Stella Adler from the Stella Adler Student Union (comprising Day Conservatory, Evening Conservatory, and New York University students)

Syracuse University Department of Drama: A Call to Action to: Syracuse University’s Department of Drama from various students and alumni

University of Central Missouri: Dear UCM Theatre and Dance from Lovers Out Loud (comprised of students and alumni)

University of Tennessee Knoxville: first letter and second letter from UTK BIPOC Theatre (comprising students and alumni)

University of Utah: statement to the department of theatre from BIPOC Artists for Awareness (comprising students and alumni)

Winthrop University Department of Theatre and Dance: A Letter of Demands from the Lights Up Initiative (comprised of students and alumni)

Ciara Diane is a New York-based freelance writer, performer, and playwright. She is a Sagittarius, intersectional feminist/womanist, Afrofuturist, and above all a storytelling experience.

Allison Considine contributed reporting for this story.