Nothing is too big or too bold for the theatres in the Gulf Shores corridor of the South. Each of the organizations I spoke to has been tackling social justice issues through performance and self-reflection in this great pause of a global pandemic. States and places with a history of injustice are now home to theatre institutions using the arts to forge a just future, and they have no intention of letting the COVID-19 pandemic get in their way. They have both paused and pivoted toward socially distant projects, as well as internally through introspection. It may be intermission for these theatres, but the next act is waiting in the wings.

Alabama Shakespeare Festival was in the middle of producing Alabama Story and Ruby, the story of Civil Rights activist Ruby Bridges, when COVID-19 caused it to close the final week of the run. Productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, A Comedy of Errors, I and You, Cinderella, and Million Dollar Quartet were all canceled as well, severely reducing income for the year.

Funding through the Paycheck Protection Program kept the festival from having to furlough or lay anyone off until the first week of June. Since then, the staff has been reduced from 85 employees to just 10. “We had to lay off a number of people,” conceded executive director Todd Schmidt. “We had to furlough some others that we plan on bringing back in September. We are continuing to pay their health insurance for three months during this time, as we’re all trying to figure out what the future looks like.”

If nothing else, Schmidt does know that the two big summer musicals, Cinderella and Million Dollar Quartet, won’t happen. “We just don’t feel that it is wise for us to reopen until there is a vaccine,” he said. “We may do some small things in a very social-distanced way. But as far as having people in the building in one of our theatres, I don’t see that happening.”

In lieu of in-person programming, the festival has produced a monologue series called Your Favorite Actors, Their Favorite Shakespeare, for which past company employees perform Shakespeare monologues, and a weekly series with festival artistic director Rick Dildine.

And while the festival remains socially distant, it is looking inward at the role it can play in racial justice. “The world has changed yet again while we’ve been in this process,” said Schmidt, regarding the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. He said that festival staff is taking time during its meetings to ask, “Who do we want to be in the future? What kind of work do we want to do? How do we address inherent and systemic racism within our own institution? Within our community? What kind of training do we need? What kind of sensitivity? What kind of opportunities? How are we going to approach hiring? And casting? And play selection?

“We are working to open up doors to what has been viewed of us because of the name ‘Alabama Shakespeare Festival’ — based on a white, male, European playwright,” he continued. “We’ve been very conscious of doing work to include all kinds of voices in our community.”

Schmidt noted a change in programming when Dildine became artistic director in 2017. “The first season Rick planed was a very different season for Alabama Shakespeare Festival from anything that had been done recently,” Schmidt said. “We did Four Little Girls: Birmingham 1963, about the church bombing in Birmingham, cast with young people from the Montgomery public school system. The idea that you can’t do shows that deal with difficult topics, like Four Little Girls or Ruby, we’ve proven wrong in this community.”

In regard to what comes next, he said, “For theatres across this country I think this is a moment that hopefully resets things, that brings stories more local, more relevant, more community-based, so that stories and our relationship to our community become deeper and more important.”

Created as the in-house theatre producer for the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, Nashville Repertory Theatre was about to end its 35th season when the COVID-19 pandemic shut it down. “We were actually projecting finishing the year with our highest-attended and best-selling season in a decade,” said executive director Drew Ogle. “But with the shutdown we lost our biggest show and our annual fundraiser. So 25 percent of our income for the year evaporated overnight.” In addition to the spring mainstage show, Mary Poppins, Nashville Rep also lost its new-play festival in May.

“We’re not attempting a complete transformation, and we’re certainly not completely hibernating in the absence of a mainstage season,” Ogle said. “We’re moving supporting programs to the forefront: community engagement, new-play development, professional development.” Among the pandemic projects are programs for their designers, at least one online musical performance, and some educational master classes.

The theatre envisions being mostly online over the summertime and then starting in the fall with some special events that can be done in a safe, socially distant way, with the goal of returning to full production late in the year. It will try to keep as much of the 2020-21 season as possible, but with modified start dates.

Still, Ogle remains realistic about the role public health plays in its programming. “We always knew as an organization that there would likely be a time where we could legally do theatre in Nashville,” he said, “but whether it was ethical or safe to do so would be a completely different discussion.”

In the pause from the pandemic came the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. “If there is a blessing at all about the COVID-19 shutdown, it’s that it gives us time and space to focus on true systemic change the way it deserves to be focused on,” Ogle said. “It can be our primary focus for a period of time instead of something that we try to do while we also simultaneously produce programming.

“Diversifying your board, diversifying your programming—that’s the easiest stuff,” he continued. “What we’re doing, and what I hope all the theatres across the South are doing, is really digging into that. Once you have that diverse board in place, are you giving them training in racial equity arts leadership? Are you building processes and structures that bring minority voices forward? Are you really empowering your voices of color to speak, and are you willing to listen to them? That’s what I hope we don’t lose when we as an industry go back to full production: that deep, deep work that’s required at this point.”

When New Stage Theatre opened in January 1966, its first production was Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? The subject matter was controversial at the time for Jackson, Miss., as was the integrated audience at the premiere.

The company received bomb threats because some in the community felt threatened by the mission of New Stage to serve diverse audiences. Those are the roots on which it was founded, and the mission it still upholds today, according to artistic director Francine Reynolds.

After issuing a statement of solidarity with Black Lives Matter in June, Reynolds said, “I have to admit we had a little bit of negative response. But I think we lost those audience members a while ago. I hate to lose an audience member, but I think we lost them over some of the work we were doing anyway.”

Although Jackson is a majority Black city, Reynolds said, “Our audience is from all areas around us, and from counties that may not be majority Black. Statewide we’re reaching a really diverse audience.” New Stage produces five plays a year plus a holiday show with a kids-only cast. Its staff is two-thirds women and 40 percent BIPOC.

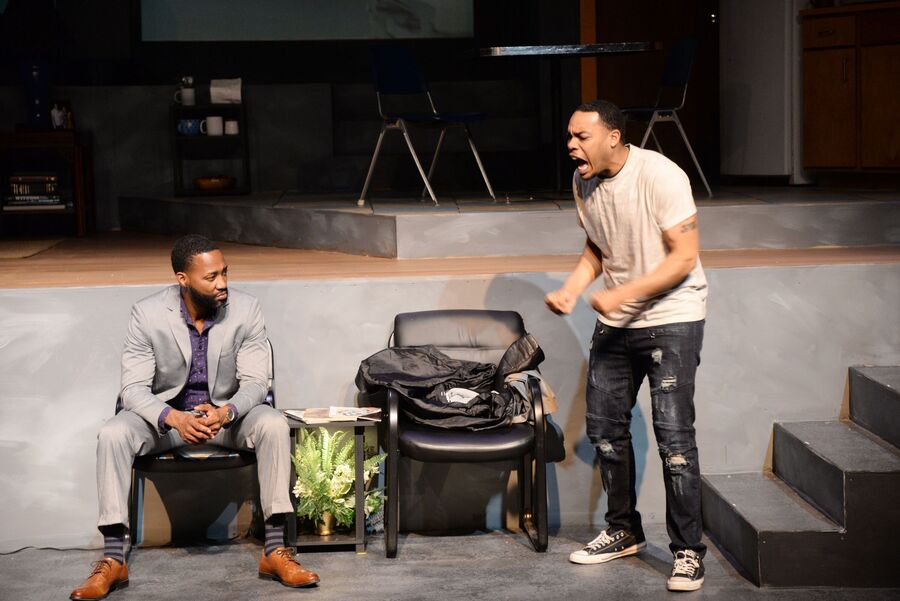

When the theatre was forced to close in March, it had just opened Dominique Morisseau’s Pipeline and had presented one post-show conversation with the CEO and president of the Mississippi Center for Justice to discuss the state’s school-to-prison pipeline, a theme of the play. “I was so excited because I had seen such a diverse audience age-wise, a lot of young people in the audience,” Reynolds said. “And on that night, which was the second night of our show, the first case of COVID was announced in Mississippi. The next night our audience decreased dramatically.”

In the following two weeks, New Stage hired a company to do a three-camera taping of its original shows for school groups that were going to receive free performances through grants. The program included Who Are You Calling Ugly?, a musical about the 1960s “Freedom Riders” called If Not Us, Then Who?, and an abridged version of Macbeth.

The theatre is also offering three weeks of virtual camp this summer, running June 29-July 18, featuring social justice theatre topics for the rising sixth through twelfth graders. The camp will culminate by having five kids at a time come to the theatre, spread out in accord with safety procedures, and perform their pieces onstage. New Stage will then cut it together to produce a virtual showcase.

In early June, New Stage put out a reopening survey to help determine when it is realistic to expect people returning to the theatre and what steps it needs to put in place to make its patrons feel safe.

While the budget will be evaluated in three-month chunks for the next year, New Stage doubts that it will be able to offer a subscription service. “We don’t know what the future holds,” Reynolds said. “I’m anxious for that survey to come back. I’m anxious for people to tell us they want us to come back.”

The NOLA Project is an ensemble theatre company in its 15th year of operation, known for presenting bold theatre in partnership with the New Orleans Museum of Art.

“In the month of March, we were planning our major fundraiser where we announce our next season,” said artistic director A.J. Allegra. “To this day, we have not yet announced what next season is, because we still live with a great amount of uncertainty about when next season is.”

COVID-19 closures caused the NOLA Project to postpone its world premiere of a Treasure Island adaptation by ensemble members Allegra, James Bartelle, and Alex Martinez Wallace, which was to be performed at the art museum’s brand-new amphitheatre. The adaptation is more inclusive in terms of female characters and people of color, according to Allegra. It has been postponed until May 2021.

In the meantime, the NOLA Project is looking at ways to use digital platforms to get content out to its patrons. “We’ve been reading new plays on Zoom and broadcasting them on our social media channels,” Allegra said. “And what we’re focused on for the fall is commissioning five new audio dramas.”

The idea is to produce works specifically for audio consumption, as opposed to play readings, as well as finding ways to turn them into some sort of communal experience, like a webinar where audience members can meet up, talk about the play, and interact with the artists.

The NOLA Project was very fortunate to not have to lay anyone off. “But by not having our major fundraiser and not being able to produce Treasure Island, which was our heaviest financial lift of the year, not just in terms of production but also in revenue, it’s basically a 30 percent financial hit for us,” Allegra said.

“We’ve always been an organization that’s very scrappy,” he continued. “Because we don’t own a venue, we are fortunate our money isn’t tied up in building costs, maintenance, things of that nature. The majority of our money goes to artists, goes to people.”

In response to Black Lives Matter, Allegra said, “Theatre activism is usually done through theatre, and right now we’re not able to do that. So how do we respond?”

Allegra is personally focused on getting anti-racism training for all the leadership of the theatres in New Orleans as well as the entire NOLA Project ensemble. “This is something that needs to occur, not as just a reaction to a tragedy but as something that is baked into the culture of theatres as a base-level expectation of what we do,” he said. “We produce theatre and we promote equity, diversity, and inclusion in our staging and boards. We have to do a lot better work.”

Victoria Mescall is a Magazine, Newspaper, and Online Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University.

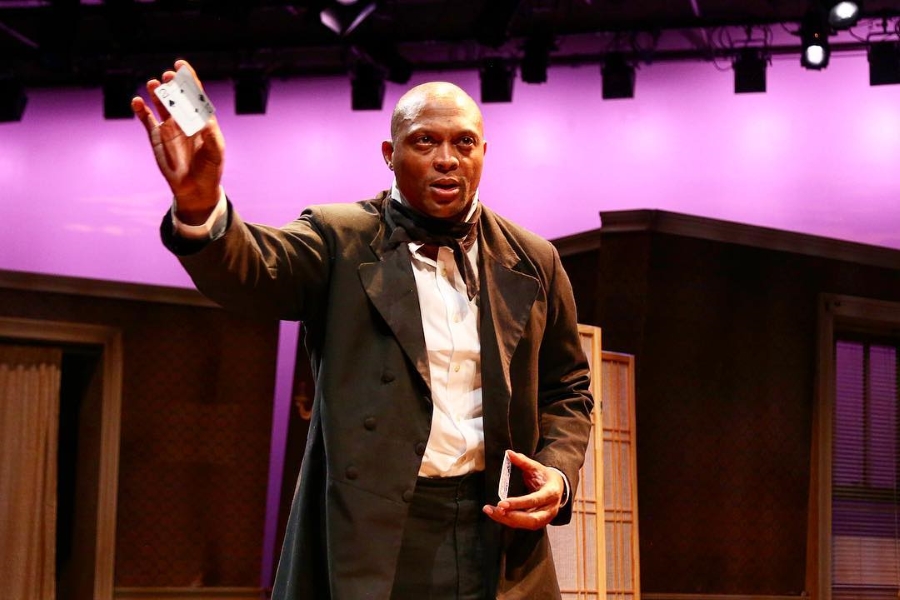

Creative credits for production photos: Ruby: The Story of Ruby Bridges, adapted by Christina M. Ham, with music by Gary Rue, direction by Sarah Walker Thornton; Topdog/Underdog by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Jon Royal; Pipeline by Dominique Morisseau, directed by Francine Thomas Reynolds, with lighting designer by Bronwyn Teague, scenic design by Richard Lawrence, costume design by Caleb Blackwell, properties design by Marie Venters, sound design by Alberto Meza, projections design by Ron Rodenmeyer; Harry and the Thief by Sigrid Gilmer, directed by Khiry Armstead