Racism isn’t just a system or a social pathology: It is also a workplace hazard, like asbestos or raked stages. It is a danger to the mental as well as the physical well-being of those subjected to it. That insight struck Nicole Brewer, an actor and director who leads anti-racism workshops, during an artEquity alumni session she attended last October, led by Gina Puntil, a Filipino Canadian involved with socially active theatre in Alberta, Canada. Puntil, Brewer recalled, pointed out how quickly other occupational work hazards would be remediated. Why not racism? For Brewer this was a light-bulb moment: It is simply unacceptable for theatre to continue this way.

She has not been alone in that realization. Last week, when a coalition of theatremakers who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) under the name We See You White American Theater (WSYWAT) released a list of demands for change in the theatre field, some saw it as a manifesto or as a statement of goals a la the Green New Deal. But viewed another way, what WSYWAT delivered for free to the theatre community was an anti-racism manual on workplace safety.

The WSYWAT movement first introduced itself to the field on June 8 with a statement invoking the principles August Wilson’s famous “The Ground on Which I Stand” speech, and promising to introduce white American theatre to itself. While it eventually gathered 82,000 signatures, there were 341 initial signatories, and Brewer was among them. As attention and buy-in for the petition grew, Brewer—whose work and workshops focus on anti-racism and providing the framework for an anti-racist theatre culture—watched as the theatre field, which once patted her on the back for her workshops while not going so far as to hire her to do that anti-racism work with them, actually seemed to be listening.

“I feel like the industry could be equated to crabs in a barrel grabbing at the hem of my skirt,” Brewer said, “trying to catch up with work that was always present for them, work that was always available, work that would have allowed them to be ready for this moment.”

This moment and movement did not come out of nowhere but emerges from longstanding frustration among BIPOC theatremakers. Reading through the 29 pages of demands, which address everything from hiring to work conditions to boards and funding, it is possible to begin to grasp the full range of what BIPOC theatremakers have been trying to say to the theatre community for years, and to see a common theme: that they have never truly felt welcome in an industry geared toward and run by white theatremakers and audiences, into which they have only fitfully been invited to do work, and even then under terms that have been variously exploitive, unequal, and harmful.

Even before the list of demands was released, the urgency of addressing inequities in the field had intensified since the police killing of George Floyd brought the Black Lives Matter movement back to the fore. Many theatres rushed to express their solidarity with the movement, but were they willing to commit to real anti-racism work? Director and original WSYWAT signatory Patricia McGregor told me that in the last few months, she has received unsolicited emails from people she had tried to have conversations with in the past about some of the issues brought to full light by WSYWAT; the gist of the emails, she said, is, “We get it now.”

She’s never shied away from these tough conversations herself, but she feels that they “are going to be very different now. I’m actually now feeling like I will be bringing people with me, and I personally will feel protected by that,” referring to the strength in numbers indicated by the signatories to the WSYWAT documents. “There’s an appetite where people, instead of me knocking on the door saying something’s not right, it feels like people are calling me saying we now know something’s not right. That feels like a fundamental change.”

Historically, these conversations about structural racism within theatre culture have been put on the shoulders of BIPOC theatremakers themselves, who have often been the only BIPOC voices in a given room. Playwright and original WSYWAT signatory Ike Holter, among many others, says that the time has come for white people to step up and hold other white people accountable, with the demands document as a handy instruction manual.

“We’ve been tasked with having to remind white people in a way that is polite or easy for them to listen to that doesn’t close the door for the next person that looks like us,” Holter explained. “We’ve been having these conversations at a disadvantage, and I’m glad that all these white allies are now like: ‘I’m going to start leading these conversations.’ Because it’s very unfair that we make Black and brown people do all this labor.”

This is labor that McGregor knows all too well. She recalled a debate with an artistic director, whom she declined to name, over a project she’d put extra work into—engaging with the communities the play was about, raising funds to bring people in—only to have the AD ask if she knew how much money the theatre had paid to do the show. The clear implication: that McGregor should be grateful to even be there.

“At the core, there are a lot of people who really do feel like this is their club,” McGregor said, “and if you are being asked to do work, you are being invited into the club. And I see the way in which that insidious mindset reveals itself. Even people who feel like they are well-intentioned, I think if they were really taking a hard look at themselves, they often view these invitations to artists of color as, like, ‘Aren’t we being generous, welcoming you to the table?’ rather than saying art should be a reflection of our culture and this should be everyone’s table. You’ve probably had an unfair advantage to be at the head of the table for a long time, for reasons that we all know. It’s not just yours to invite people to, and they have to stay well behaved in your mind in order to stay.”

The bottom line is that BIPOC artists have never truly felt welcome, even when invited in, because they haven’t been given a sense of shared ownership. While the demands document spans every sector of theatre—production, marketing, development (of both the literary and fundraising kind), unions, and, yes, even the press—the first section of the demands, under the heading of “Cultural Competency,” acts as a sort of thesis statement for the whole document, taking clear aim at the idea that theatre is some elitist club into which only certain accredited artists are allowed.

Tara Moses, director, playwright, and citizen of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, has faced this sort of gatekeeping since she was a child. At 16, she was told, in front of a group of fellow teens, that she couldn’t be the lead in Snow White because, well, the show was called Snow White, not “Snow Brown.” She left acting, she says, because she kept getting told she wasn’t what people expected—she was told she looked Puerto Rican.

“As a director and playwright, I’ve seen that theatre is not ready for Native stories,” said Moses, another original signatory to the WSYWAT statement. “And I’ve found that I can’t run my rehearsal room in the Native way of storytelling, that I have to stick to Eurocentric colonial practices, including at Serenbe Playhouse,” a Georgia theatre that recently dismissed its entire staff after being charged with persistent racist practices. “I have been calling and asking for these demands and they were not met. When I was a fellow at Arena Stage, when I participated in the Lincoln Center Directors’ Lab, they were not met. We’ve been attempting to have these conversations with our white counterparts for decades. Now is the time.”

Leading WSYWAT’s cultural competency section is a demand for the naming and acknowledgement of “American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian tribal land and its Native peoples who have lived, currently live, and will live on the land where any theatre activity happens.” This, like all of the demands, is to be implemented across the theatre field, from Broadway down through all levels of theatre.

“What I really appreciate in this document is that land acknowledgement is seen as a living, present thing, something to put into practice,” Moses said. “It’s not, ‘Oh, we’re going to memorize a speech and Google how to pronounce these tribal names.’ It’s about creating meaningful relationships with the Indigenous people whose lands you occupy. I always say, do the land acknowledgement, but also connect with elders in your population.”

As Moses points out, this acknowledgement, alongside the following demands for recognition and acknowledgement of the enslaved Africans who lived and were enslaved on the grounds where many theatres stand, and a demand for the recognition of the exclusion, exploitation, and misrepresentation of Latinx, Asian, Middle Eastern, and all people of color, is a way to begin to grapple with a reality we too easily ignore: that the lands we live and work on were stolen from Native people and built on the backs of Black people. Director and artistic director of California Shakespeare Theatre Eric Ting, whose East Bay theatre stands on the historic home of the Ohlone nation, points out that these initial demands are essentially about dethroning whiteness as the dominant or the default.

“If the impulse is to genuinely create a space that is inviting to everybody,” Ting says, “if we really say we want everybody, all identities, if we want you to all invest in this as if it is your own, you have to decenter the most powerful identity. If it’s simply about inviting POC into white spaces—even as I say that, you can see how that isn’t enough.”

Even as someone who’s relatively informed and progressive on Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) issues, Ting says that the bullet points listed in the demands’ cultural competency section are all things he would have liked to have had guidance on to shift the culture of his own organization and audience—again, like a workplace manual. Indeed, another major point of this section is the need to create a safe, anti-racist environment in theatre by having regular EDI and anti-racism training.

The demand for this training is aimed at every level of the industry, from boards and executive leadership all the way down to contractors and part-time staff. Between ongoing training for leadership, boards, and staff, quarterly training for the rest of the staff and contractors, and workshops at the beginning of each rehearsal or tech process, it might be easy to let thoughts of “where will the money come from” and “how much time will this take” creep in. But, as Brewer points out, these trainings are not a one-off or a one-size-fits-all. When she offers them, she works to meld her training to the specific needs of the individuals and institutions she’s working with.

“When I’m working with people, I’m like, what is your own individual positional power?” says Brewer, who also encourages cultivating a foundation of an individual anti-racist ethos through multiple forms of training and knowledge. “What are your privileges? What are the things that you still believe to be true that are actually false? How you’re undoing that and how you’re going out and practicing depends on how often you’re in practice.”

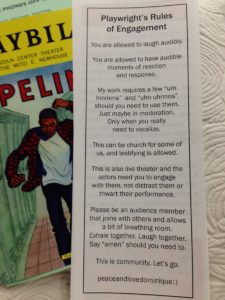

These anti-racism practices don’t end with how the art is made. The expectation is for these institutions to also incorporate that anti-racism into the environments created for BIPOC audience members, including (but not limited to) promoting statements of inclusion for different cultural practices among audiences. It was almost five years ago that playwright Dominique Morisseau wrote about her experience with white etiquette shaming at the theatre, where she came within seconds of seeing the headline “Award-Winning Playwright Slaps Patron at Theatre.” Since then, Morisseau crafted her “Playwright’s Rules of Engagement” for the Off-Broadway run of her play Pipeline at Lincoln Center. The rules specifically invited reactions outside of the stereotypical (and white-centric) theatre experience of sitting quietly in a seat for two hours with your mouth closed: audible laughter, response, and vocalization. She noted that actors in live theatre thrive on engagement, as long as it doesn’t derail the performance. “This can be church for some of us,” she wrote, “and testifying is allowed.”

That’s just one example of how Black (and other BIPOC) artists have pushed back against the exclusion and alienation they’ve been made to feel in their attempts to enjoy the art they love. And it’s in line with many of the other opening demands from WSYWAT: fair and equitable credit for the work BIPOC artists often put in outside of their contracted job (McGregor putting in work to engage with and fundraise for the communities her project should be speaking to, Morisseau taking the time and energy to make sure her audience feels comfortable within a white institution); institutional leaders seeking out and valuing those with different viewpoints; defending the right of BIPOC artists to freely interpret and reimagine canonical work by white authors; and prioritizing the cultural care of BIPOC artists, which would include ending tendencies to tokenize and fetishize, and hiring therapists for content that deals with racialized experiences and trauma.

In short, what the Cultural Competency portion of the document does is set the terms for the rest of the 29-page document by making the point: It is past time to lean in and actively listen to the needs BIPOC artists have been calling out for decades.

While the WSYWAT movement has no attributed authors or leaders, Brewer did say that the core group behind it was very calculated and organized in seizing this moment of pandemic-lockdown pause to share stories and share experiences and demands without apology. As Bay Area director M. Graham Smith tweeted recently: “Dear American Theater, please take this advice from a 5-year-old: ‘When I’m in a time-out I’m supposed to think about my choices.’” The collective’s choice to seize this time-out and give the theatre field a series of prompts and challenges for self-examination has fundamentally changed how Brewer looks at the potential for a better theatre landscape. While she noted that it still could take a full decade to even see half of these demands fully realized, she feels that the possibility of real change is much higher than before COVID-19—change that she previously thought she may never see accomplished in her lifetime.

“I was like, this is the work I’m doing,” Brewer said. “It’s going to be better for my kids and it will be better for my kids’ kids. I won’t be able to reap that harvest. But to dare to dream that it is possible for me, in 10 years, to be part of an industry that is radically different than before—that’s worth the work for me.”

For her part, McGregor said she looks at this fight through the eyes of those she mentors.

“Almost all of my assistant directors are women of color,” McGregor said, “and I hope that this journey is easier for them. I’ve often felt sad when they become disappointed or disillusioned, because they see a fight that I’ve had to fight against systemic racism or injustice or misogyny. Their bubble is popped a little bit. Then we talk about how you negotiate past that. I hope that for future generations of artists, it’s easier to do the work with rigor and love and to have more opportunities to do work and experimental work, and not have to fight so hard or to feel so alone when you’re fighting.”

McGregor said she has always longed for the moment when individuals might come together for a cohesive call to action and real change. This is that moment, she feels, when a real appetite to look at these issues meets an unplanned hiatus and a chance to regroup. There are still aspects of this movement that need to be fleshed out—including what kind of accountability model, if any, could be put in place to see that the demands are met. But a question McGregor posed to me continues to stand out: “If we’re resisting signing onto these practices, why are we resisting that?”

That’s a question theatre leaders, boards, theatremakers, and patrons will all have to grapple with moving forward. If they feel daunted by the scope of the demands, they need not. As Moses put it, “There are things in here that can be implemented today, and there are things that would take more time, like restructuring budgets and hiring practices. Our field has shifted dramatically before. We can do it again.”

Added Holter, “There are a lot of places for you to pick and choose where you want to focus on. It’s really good that a large group of people are saying, ‘We’re trying to help you—this is what we can do.’ The next step is for the people who have the most power to finally say, ‘Okay, let’s make these changes.’ Now is the time we can.”

Rob Weinert-Kendt contributed reporting to this piece.